How to amend Constitution after the landmark BBI court decision

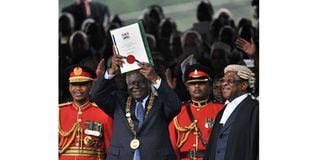

President Mwai Kibaki lifts up the new Constitution soon after its promulgation at the Uhuru Park grounds in Nairobi on August 27, 2010.

What will it take in the future to change Kenya’s 2010 Constitution following the High Court’s judgment on the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI)? In many ways, the answer to this question is in the judgment.

But first a note to offer context. It is not onerous to change many provisions of the Constitution.

However, BBI has been so contentious because it was conceived to make changes that are intended to benefit the political class and not the people. Therefore, in a bid to inoculate itself from political subterfuge, the Constitution created principles and processes that make its core aspects quite onerous to change.

What the judges said

The judgment contains three key holdings that illuminate what it will take to change the Constitution in the future. I use the word change here and not amend to signal that the judges considered both what it would take to amend the constitution as well as (to some extent) to overhaul or replace it. The holdings are on basic structure, popular initiative, and the trigger for multiple questions in a referendum.

Basic Structure

In discussing the basic structure, the judges mostly dealt with the nature of the power to amend the constitution. They clarified that, in constitutional change, there is a difference between constituent and constituted power.

Constituent power is the power innate in people as people, which is beyond law. It is the notion that the people make the law and not the other way around. The judges further clarified that constituent power has two facets to it: primary and secondary constituent power.

Primary constituent power is the power to replace/overhaul or “radically change” the constitution. Primary constituent power is relevant in Kenya in two ways. First, when people are making an entirely new constitution. Second, when people want to amend provisions of the 2010 Constitution that form its basic structure.

In either case, the judges said, a process outside the Constitution will apply and which would at least have four parts to it (i) civic education (ii) public participation (iii) constituting constituent assembly (iv) referendum.

Secondary constituent power is one that people have within the existing Constitution but specifically reserved for making non-fundamental changes to the Constitution that don’t affect the basic structure.

What of constituted power? Constituted power is amendment power that is given by the people in (or through) the Constitution to other organs. These organs include Parliament, county assemblies and the Executive.

Popular initiative

The court was asked to decide who has the power/right to initiate constitutional amendment through a popular initiative. The court’s answer is straightforward. Only the people, in their private-citizen capacity as voters, can do so.

Importantly, the court unequivocally found that a state officer and especially the President as well as any state agency cannot be a promoter of a popular initiative.

This finding is grounded primarily on two reasons. Firstly, the court found that the popular initiative pathway is the tool that the people reserved for themselves whenever they wanted to change the Constitution using their direct exercise of sovereign power under Article 1, as opposed to the power they donated to elected representatives.

This was necessary to ensure that the people retained an option – whose fate was not hinged on Parliament– to amend the Constitution. Secondly, the court was even more specific on why the Constitution does not permit the President to be an initiator/promoter of a popular initiative like Uhuru did with BBI.

The President has been assigned the role of determining whether a popular initiative should go to a referendum. This makes the President a critical “referee” in the amendment process.

Multiple question referendum

The third main issue that affects how the Constitution can be amended relates to framing of the question(s) for referendum.

The court held that, where a constitutional amendment bill is an omnibus bill – that is, it seeks to amend more than one issue – then each issue for amendment must be presented to the people as a separate question at the referendum.

The court justified its finding on the basis that, one – having only one question at a referendum on an omnibus bill puts a voter in a dilemma where they are not able to exercise free choice to vote only for the things they like and reject those they don’t like.

Two, the court noted that Article 255 – 257 speaks of “amendment” and not “amendments”, which leads to a logical conclusion that what has to be presented to voters at a referendum is a question on each amendment and not one question for the entire bill. Three, the court noted that the Elections Act 2011 already provides for a possibility where more than one question may be presented to voters at a referendum.

Amending the Constitution

What does the court’s holding in respect of basic structure, popular initiative and multiple-question referendum mean for anyone who, in the future, hopes to mount a successful constitutional amendment especially on non-minor amendments of the constitution?

The nature of proposed amendment

The starting point is a thorough understanding of whether the provision(s) proposed to be amended relate to basic structure. If the proposed amendment is not about the basic structure, then the amendment task is less onerous.

However, if it forms part of the basic structure, the next question is whether the proposed amendment relates to provisions/aspect that are unamendable eternal clauses or the amendable basic structure clauses.

If the proposed amendment is part of the amendable basic structure, those sponsoring the amendment (working with responsible state organs) must meet the four pre-conditions of amending basic structure.

These are civic education; public participation; putting together a constituent assembly and finally holding a referendum.

But who determines whether a proposed amendment involves basic structure? There are three organs that can decide or facilitate that determination. The first is Parliament, especially if the proposed amendment is proposed under the parliamentary initiative pathway. The second is the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), especially on a Bill brought through the popular initiative route. The third and ultimately the most authoritative are the courts.

There are two ways in which courts will be key in helping clarify on the nature of proposed constitutional amendments. The courts can do this pre-emptively where they are invited to pronounce early enough the nature and viability of a proposed amendment. They can also do it after the fact – at the tail end of the amendment cycle.

A minimalist approach to amendments

A second strategic consideration is taking a minimalist approach when choosing what to amend. By a minimalist approach I mean the fewer the issues contained in an amendment Bill the better. In fact, my own view is that a Bill to amend the Constitution should only have a single issue. Instructively, a minimalist approach means that in the end voters are presented with only one or very few issues to vote for at a referendum.

Last thoughts

To be sure, the BBI judgment has not made amending the Constitution impossible or unjustifiably onerous. It has instead helped tame the possibility of abuse of amendment power by political and other categories of the elite. It requires that any serious effort to amend the Constitution must be based on a more reflective, deliberative and genuine need for amendment and – perhaps importantly – be hinged on posterity and not the perishable political life of those wielding formal or informal state power.

@waikwawanyoike