How we fell in love with ghosts

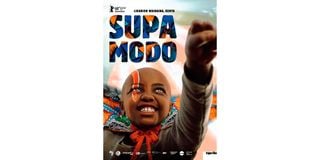

The 2018, “Supa Modo”, directed by Likarion Wainaina, is the story of Jo, whose dream is to be become a superhero.

What you need to know:

- Our writers, poets, and filmmakers spent many years trying to fix what was broken.

- These young ones, spend a lot of time making the future.

The Nommo Award Long List was announced this week. The Nommo Awards honour works of speculative fiction by Africans. They are the fruits of The African Speculative Fiction Society.

Which brings us to the question of what is speculative fiction. According to the Speculative Literature Foundation, it is a “catch-all term meant to inclusively span the breadth of fantastic literature, encompassing literature ranging from hard science fiction to epic fantasy to ghost stories to horror to folk and fairy tales to slipstream to magical realism to modern myth-making — and more. Any piece of literature containing a fabulist or speculative element…”

So, it is the kind of literature many older African folk haven’t and are unlikely to read. They are missing out. Not all of them, though. Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who has been described as one of the world’s greatest storytellers, has his “The Perfect Nine: The Epic of Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi”, an origin myth of the Gikuyu reimagined, listed in the 2021 Novel Long list. Originally published in English in 2018, it is a retranslation from wa Thiong’o’s original Gikuyu version.

The second work by an East African in the Novel category is “The First Woman”, by Ugandan writer Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi. It is an origin myth of motherhood.

Unsurprisingly, the Nigerians rule the roost. The East African showing is passable, mostly Ugandan and Kenyan writers. There is a story there.

Murderous dictators

To get to it, it is well to remember that speculative fiction was not really a thing in East African, and indeed African, literature until recently. To name a handful, today, Amos Tutuola’s “The Palm Wine Drinkard”, published in 1952, might fit the bill, but perhaps better, tormented Nigerian poet Christopher Okigbo’s “Labyrinths”, (1971), and Ali Mazrui’s “The Trial of Christopher Okigbo”, also first published in 1971, would sit well in the category.

Literature those days was supposed to be life and world-changing stuff. It was supposed to fight colonialism and imperialism. To rescue African tradition and religion from the deep grounds where the mzungu had buried them, deeming them backward and heathen.

There were new nations to build, and writers were expected to show us that elusive path forward. And after independence, the nationalists who fought for independence quickly became as bad as the colonisers, and turned corrupt and murderous dictators. Soon, the soldiers came in, kicking them out in coups, and going on to be even more corrupt and murderous.

Yes, writers could dive into origin myths and folktales, but for the purpose of finding lessons to teach us about how to conquer the present, and find things that made us proud as Africans. Speculative fiction, all the science fiction, horror, superhero fiction, fantasy, and supernatural fiction was considered to be idleness, even counter-revolutionary. It would be playing the fiddle while Kampala, Nairobi, Lagos, or Dar es Salaam, were burning.

We have come a long way.

Consider the East Africans who landed on Nommo’s 2021 Novella Long List. There is Dilman Dila, a Ugandan writer, filmmaker with his “A Fledgling Abiba”. We have Kenyan novelist Moraa Gitaa, with “The Kigango Oracle”.

And there are more of them than you can throw a hat at on the Short Story List. Kenyan writer Alvin Kathembe with “The Game; Rwandan-born Aline-Mwezi Niyonsenga with “That Which Smells Bad”; Ugandan writer, screenwriter, sketch artist, and blogger Derek Lubangakene with two, “Fort Kwame” and “The Cult of Reminiscence”, another Ugandan writer John Barigye with “The Red Earth”; Kenya’s Odida Nyabundi in with “Clanfall: Death of Kings”, and Kenyan storyteller Shingai Njeri Kagunda – described somewhere as “an Afrofuturist freedom dreamer, Swahili sea lover, and femme storyteller – with “And This is How to Say”.

Serious illness

On this eastern end of Africa, while there are many tormented souls and rebellious spirits, Kenyans and Ugandans express both most dramatically. Horror, science fiction, revamped fables, and reimagined myths are their weapons.

They differ from the elders of letters who came before, in that they imagine the future – and dystopia – more vividly.

If you follow the genre, you might remember “Kati Kati”, a 2016 Kenyan film directed by Mbithi Masya about a young woman with no memory of her life or death, who is helped to settle in the afterlife by a ghost.

In 2010, there was “Pumzi”, as sci-fi as films get, directed by Wanuri Kahiu, about Africa in the future, 35 years after a World War III, and we are killing each other over water. And more recently in 2018, “Supa Modo”, directed by Likarion Wainaina, the story of Jo, whose dreams of becoming a superhero is threatened by a serious illness – until her village steps up to help make it come true.

The biggest change in these our lands, you might say, is that our writers, poets, and filmmakers spent many years trying to fix what was broken. These young ones, spend a lot of time making the future. As the poet Lucille Clifton put it, “We cannot create what we can’t imagine.”

Mr Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer and curator of the Wall of Great Africans. @cobbo3