Premium

Kondele incident and our diabolical march towards normalising violence

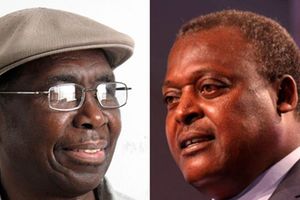

Youths attempt to block DP William Ruto’s motorcade from accessing Kondele roundabout in Kisumu on November 10, 2021. Eric Ng’eno writes it became clear that for many Kenyans, “violence per se is value neutral; it is not reprehensible in and of itself”.

What you need to know:

- Debate was polarised between two principal tendencies, each armed with strategic narratives to bolster both offensive and defensive tactics.

- A lingering subtext in the political domain was that outraged citizens of Kondele were expressing their disapproval of Ruto’s rhetorical onslaughts on Raila Odinga.

Senator Gideon Moi did a thing. While condemning the violence that disrupted Deputy President William Ruto’s tour of Kisumu County, he emphatically pointed out that his disapproval applied to all manifestations of violence, whether “real or stage-managed”.

All violence is real, of course. Yet at the same time, this does not mean that the good senator committed a faux pas in distinguishing classes of political violence. What he did was plug directly into the abundant repository of arcane vocabulary for evaluating Kenyan violence.

At issue in the Kondele outrage was the assignment of accountability and legitimate victimhood in conformity with salient political narratives. Going by social media interventions, it was unclear whether Ruto would eventually emerge as a victim of vicious political reprisal by irate supporters of his nemeses, or whether his was a case of just deserts – perhaps he did something to elicit rage, thereby justifying the violence – or if indeed, his team had staged the entire terrifying fiasco to profile his political adversaries and score a few points.

Nonetheless, debate was polarised between two principal tendencies, each armed with strategic narratives to bolster both offensive and defensive tactics and vying to get on the right side of the violence, and jostle rivals to the adverse end.

The facts of the incident thus dissolved into the raging mists of intemperate exchanges. However, it became clear that for many Kenyans, violence per se is value neutral. This is to say that the incidence of violence is not reprehensible in and of itself.

Victims or abusers

Rather, outrage, sympathy, support, repudiation, condemnation and defence are negotiated in discursive reorganisation of memory, revision of facts, rationalisation of events and the instrumental apportionment of motives and grievances. The results are often confounding and even counterintuitive to the uninitiated. Obviously, characterisation of facts as “real or stage-managed”, forms part of the initial sequences towards the designation of victims or abusers and allocation of legitimacy.

Ruto’s onslaughts on Raila

The clamour can spring astonishing reversals. Take for instance the effort, anchored by the spokesperson of the National Police Service, to set out ‘alterative facts’ profiling Ruto or his team as the authors of their misfortune. This narrative attributed the violence suffered by the Deputy President to certain interesting misunderstandings occasioned by their acts and omissions.

A lingering subtext in the political domain was that outraged citizens of Kondele were expressing their disapproval of Ruto’s rhetorical onslaughts on Raila Odinga, the reigning local potentate.

According to such discourse, a target of violence is not necessarily the victim. The existence of a ‘cause’ often suffices to invert accountability, so that a violator is constructed as a righteous victim avenging himself, and the object of the violence actually a malevolent provocateur who had it coming.

The idea that all violence, howsoever manifested, is ipso facto reprehensible, seems exotic. At police stations, victims of battery and grievous harm first have to establish that they did nothing whatsoever to elicit, provoke or justify the infliction of harm. We long crossed the cardinal threshold towards normalising violence in our society.

A few years ago, we saw a video of a phalanx of policemen viciously applying heavy truncheons on prostrate youths. When it turned out that they were university students cornered during a strike, the public seemed to understand and even approve, and that was the end of the matter.

Government often employs brutal violence to achieve quotidian administrative and policy ends. The entire lockdown period was marked by immense police violence, as though the Sars-Cov-2 was a matter of guns and handcuffs.

Politics of Kondele

We have witnessed our government, as recently as 2021, evict squatters, residents of informal settlements and other underprivileged citizens in the dead of a freezing night by demolishing and even burning their dwellings and their children’s schools.

Yet all this atrocity pales in comparison to what we reserve for children and young persons. In the wake of school unrests frequently featuring arson, the campaign for the restoration of corporal punishment has hit a crescendo. Quick analysis inevitably demonstrates that the modern school is an intersection of multiple contending stakeholder interests.

Dreadful state failure has lately attenuated matters to an unsustainable degree.

The government, which expanded enrolment beyond thrice the full capacity of most institutions, also curtailed all development support, frequently delays capitation and drives tutors and school management to near insanity with a diabolical multiplicity of draconian ultimatums. Add to this a blistering calendar aimed at recovering the year lost to the Covid-19 lockdowns, and from simmering ferment impending explosion gurgles.

The same government is also quick to prescribe violent abuse of minors as the sole antidote for the intractably complicated problems in the education sector. This makes public schools incredibly vulnerable to anyone possessing motive and means to perpetrate terrific sabotage.

The fiery politics of Kondele and the rabid fanaticism with which corporal punishment of pupils is propounded are dismaying signals of a society conditioned by successive violent regimes to normalise senseless brutality in place of solutions. What a shame.

The writer is an advocate of the High Court and a former State House speech writer. @EricNgeno