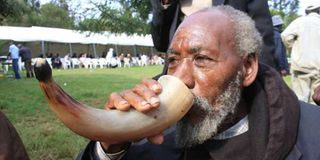

A man drinks muratina during a traditional ceremony.

Governments the world over have an hypocritical relationship with alcohol and tobacco industries. Kenya is not any different. The adverse effects of alcohol and tobacco on users’ health and society should be enough reason to ban them. But due to tax benefits to the national treasury, they would rather turn a blind eye to the deaths and mental health implications.

The focus of many governments is to ban hard drugs such as cannabis, cocaine and heroin. The punishment for people who smuggle or consume these illegal drugs is usually severe—such as life imprisonment and the death sentence. The anti-narcotic policies adopted by many countries have not been a deterrent. If anything, they have led to a rise in more extreme measures by smugglers to expand their trade.

Narco-terrorism has become common in a few countries, with the smugglers using violence to control drug routes and supply. The general view is that the anti-narcotics policy or so-called ‘war on drugs’ has failed.

Driving drugs, alcohol and miraa (khat) underground has a more negative impact on society than adopting a more liberal but controlled approach to their consumption. The tough stance taken by the government in banning local brews is what is leading to rise in usage of illicit alcohol.

Many Kenyans, especially in rural areas, cannot afford the expensive alcohol being produced by the few industries with the monopoly to do so. We need to diversify the industry so as to create healthy competition in the manufacturing of alcohol.

I don’t know the difference between busaa, chang’aa and muratina but, from the sound of it, these are local brews that are dying to be patented, refined and sold to customers with a taste for them. Mnazi (palm wine) could be produced and packaged in a clinical environment to help local palm wine harvesters to find legal markets for their produce. The focus should shift from banning local brews to manufacturing them to reduce over-reliance on illicit alcohol by drinkers who cannot afford the expensive formal ones.

Banning local brews will only push them further underground, where its production is left in the hands of an unregulated industry under an unhygienic environment. It is not surprising, therefore, that all sorts of chemicals end up in the production of the liquors to increase their potency. Hence, why we end up with blindness and deaths in the local dens. And the government has a hand in it, albeit indirectly.

Compassion

The trend will not be reversed by weaponisation of the war on local brews. Instead, a softly-softly approach is the way to go. First, bear in mind that most producers of the local liquours are uneducated unskilled women. Through compassion, and in a bid to dissuade them from producing the deadly alcohol, they can be given an alternative source of economic activity.

Every time cases of death or blindness from illicit brew are reported, the government’s modus operandi has been heavy-handedness by sending police into bars and dens and/or a knee-jerk reaction to establish rehabilitation centres for heavy users of local brews. It is naïve and lazy to suggest that only those drinkers in the local dens are addicts. Middle-class addiction is just as problematic. Addiction is not only of alcohol but miraa, cocaine and heroin. Towns such as Mombasa are reporting an inrcrease in cases of young people addicted to cocaine and heroin. Isiolo, Marsabit and the northeastern region in general suffer from miraa addiction. Cherry-picking addicts won’t solve the nationwide addiction problem.

Kenya, therefore, needs a nationalised policy on rehab. Treatment of mental health problems emanating from drugs, miraa and alcohol was always confined to the back burner. Even NHIF does not offer comprehensive cover to mental health patients, and this is something that now needs to change.

Having said that, I am sure the first response will be about throwing billions of shillings to mental health (read: corruption). However, I believe there are less cost-effective ways to help those suffering, such as use of talking benches, which have proven successful in Zimbabwe. The nurses we are offloading to other countries can be employed to offer support to addicts who end up suffering mental health breakdown. Addicts are not criminals but patients and should be treated just as those suffering from other ailments.

The first thing to do is to regularise the local brew industry and make it safe for users. Most importantly, it is an economic angle that we tend to disregard. The fact that there are manufactures of local brew, albeit illegally, and there are takers, it means there is money being generated.

The government’s effort to regularise the industry will help it to create another avenue for raising taxes. French wine and champagne are local brews made from grapes and generate huge taxes for France. Why, then, can’t Kenya commercialise muratina, busaa and chang’aa for tax?

- Ms Guyo is a legal researcher. [email protected]. @kdiguyo