Premium

Magesha Ngwiri: Ignore hecklers, give peace a chance

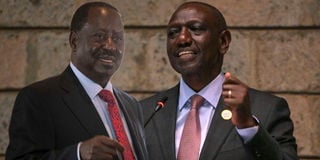

Opposition leader Raila Odinga (left) and President William Ruto.

To cite a much-hackneyed adage, there seems to be some light at the end of the tunnel on the political front.

This is good news for Kenyans who have been worried sick that their country may not survive prolonged violence on the streets during which destruction of life and property is rife and disruption of everyday life normalised.

It therefore came as a pleasant surprise when it was reported that the President had agreed to hold talks with his arch-nemesis, Mr Raila Odinga, albeit through emissaries, and eventually, one hopes, through face-to-face negotiations between the two that may result in lasting amity. This will be a win-win situation.

However, it raises the question as to why the country had descended into the dark tunnel in the first place, and the answer can only be one: Political leaders pushed it there because that seems to be their comfort zone.

It also seems that the hardliners, for whom any form of negotiation between the government and the opposition is anathema, are not happy. These are the chaps to whom any mention of dialogue makes them conclude a “handshake” is in the offing.

They come across as folks who are afraid of something –maybe the potential dilution of power, or the fact that the lies and propaganda they have been spouting will be exposed for what they are.

Of course, to a certain extent, they have a point. Democracy is about a government and an opposition, not a mongrel polity which leads to a “hideous uniformity of mind” on public issues.

In a situation where a government cannot be checked, it is the governed who suffer, for there is no one to hold it to account should things go wrong. And judging from the events of the past two weeks, things can go terribly wrong. How else to explain the brutalisation of civilians in the so-called “hotspots”, the abduction, incarceration and torture of suspects, or even the arrest and arraignment of critics on trumped-up charges which leaves the government with egg on its face?

A government that is intolerant to dissent just exposes its insecurities, but one that accommodates differences of opinion is strong indeed. That is why it beats reason for a government to weaponise its internal security organs against the citizenry.

Which is why, all sensible Kenyans should applaud the decision by President William Ruto to reach out to Mr Odinga to avoid further unrest whose impact no one should ignore. At the same time, this is a situation that calls for give and take as well as good faith.

Own disbandment

It would be folly for the opposition to insist on conditions that would be difficult to fulfill. Self-preservation is an overriding objective for any government, and setting conditions for its own disbandment is, obviously, a non-starter.

Having said that, let’s look at this matter of street turbulence and the reaction of the State in its proper perspective.

For four years after Mr Daniel arap Moi became president on August 22, 1978, he was an energetic figure, a kindly benevolent uncle to many.

However, in his fourth year, he was badly rattled by an attempted coup and became a ruthless dictator for the next two decades, jailing, detaining and breaking his opponents, real or imagined.

President Ruto has been in power for only 10 months and it appears he has been jolted by maandamano to the extent that he may have started imagining the worst.

In my view the State reaction to the protests was way disproportional to the threat, and in any case, it is a little too early to flex such heavy muscle. My unsolicited advice to the President: Shun those among your advisers who would urge you to turn this country into a police state. Nothing good will come of it in the fullness of time.

On another note, recently, one of my readers raised a most intriguing issue. This was in reaction to an earlier commentary in which I asked why, in general, African governments fail so miserably. He asked whether we in the media are willing to satisfy ourselves with commenting on issues of bad governance, and then watching unconcerned as situations continue to deteriorate, or whether, having understood what was wrong, we are ready to take the next logical step—that of lighting the fire that will eventually bring about a transformation.

My reaction was that, no, journalists, opinion writers, news analysts and bloggers are not politicians and are inadequately equipped to bring about change except through suggestion.

Their job is to report news, analyse it, interpret it and, if they must comment, use their influence to change perceptions, ideally for the public good. Anything beyond that makes them political activists, in which case their views will be coloured by emotions that are rarely ever objective.

In short, journalists will raise the alarm when they see the country hurtling towards the abyss, but they may neither have the time nor the resources to demonstrate in the streets against the perpetrators of misrule. In popular parlance, both journalists and politicians must, of necessity, keep to their lane.

- Mr Ngwiri is a consultant editor; [email protected].