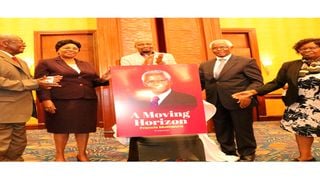

Dr Francis Muthaura (second right), with his wife Rose (right), together with Public Service Cabinet Secretary Mr Moses Kuria, former Public Service CS Prof Margaret Kobia and Dr Henry Chakava, the chairman of East African Educational Publishers (EAEP), during the launch of Dr Muthaura’s memoir, ‘A Moving Horizon,’ at the Nairobi Serena Hotel, on November 2, 2023.

| PoolOur Columnists

Premium

Muthaura is the gold standard in leadership and what a man should be

As I walked in, I caught a whiff of (steamed, I thought) vegetables. Broccoli, baby corn, cauliflower, baby peas, that kind of thing, not managu and terere.

I noticed that, behind the gentle welcoming smile, the man I had come to see was running his tongue over his teeth and inner cheeks in the manner of one who had just had a nice, satisfying lunch. There was a glass of hot water on the table.

I had come to see Dr Francis Muthaura, Head of Public Service, at his Harambee House office, egged on by Sam Mwale.

Mr Mwale also has a smile that he can’t seem to repress, even when he is unhappy. I had waited at his office (he was Chief Administrative Secretary) for HOPS to ask for us.

I noticed the reading material on his occasional desk was on the Elemi Triangle; I’m a nosy ‘noticer’ of things.

Mr Mwale is a sharp cookie, which, coupled with his calm, formal, reassuring manner, made him one hell of a public servant. He had been a columnist for some of the papers I edited and we got on rather well.

Mr Muthaura is slightly built—not short—with the kind of ascetic, slim physique that you get from a lifetime of discipline, not seasonal pumping of iron and gorging on fat.

It was during the Government of National Unity days, a time of some conflict and, surprisingly, good progress on many fronts too, including the Constitution.

The easy manner, and the friendliness, do nothing to soften Mr Muthaura’s sharp gaze; there is authority and a strong will behind those eyes.

I was very surprised. I had expected a fulminating hawk, a bully, perhaps even a fierce Raila-baiting Kibaki ideologue. Instead, I found a friendly, easygoing, intelligent, talkative old man who engaged me in stimulating conversation.

He didn’t have the bureaucrat’s usual distrust of journalists; he spoke freely. His mind was a like a pack of hardworking sheep dogs; herding ideas from far and wide towards a funnel, and the funnel was about solving Kenya’s problems.

I hadn’t met a policy wonk quite like that one, combining a good, almost academic, intellect with solid experience, having made his bones in the trenches of an actual Third World government bureaucracy. I was more familiar with NGO theorists.

I met Mr Muthaura again many years later, long after his retirement, at a charming dinner organised by his agemates and former colleagues to celebrate one of his many achievements. And he was just the same way—thinking about the problems the country faces and talking about what could be done, tirelessly.

High regard

When I think about it, I hold him in very high regard: A man who was very powerful in government, so clever and capable, yet humble and simple and utterly uninterested in becoming an overnight billionaire and stealing public funds to go and buy expensive suits. To me, he is the gold standard in leadership and what a man can and should be in this world.

In some countries, people like him would have a ready position at an institute, foundation or government-affiliated college, with an office, staff and funds to conduct research and teach the next-generation technocrats. Maybe he is already doing that; I don’t know.

I got stuck in the mud last weekend, partly because of my poor off-roading skills and also that some of the roads leading to my home in the countryside have been reduced by the heavy rains to bogs. There is a tarmac road but the contractor didn’t do the bridges; so our home was cut off after a river started running over the bridge. I got stuck trying to find a path home.

And as I paused in my huffing and puffing trying to get my pickup out of the ditch, I noticed how many young men were on the road. Dozens of them, healthy, happy well-adjusted kids, moving in bands the way local young men do. Their eyes were clear, their bodies strong; meaning they had not started smoking the bhang and drinking the moonshine that was killing their elder brothers, uncles and fathers.

How many of these young people would end up as Muthauras, providing honourable service to their country? And how many would end up as those whack jobs, threatening to stir women with sticks? Was anything, or can anything, be done to ensure that the whack jobs are fewer and far between and the better type more?

What broke my heart about this Mwangaza impeachment saga is the misogyny of some of the leaders, yes, but it’s also the evidence that this is a widespread disease: There was an excited gang egging on the man threatening to “stir” the female rival. And if the people were innocent, why would they elect the whack jobs?

Meru is a land of shameful contrasts. On the one hand it produces the most exemplary, bold and selfless people; they are many and you most probably don’t know much about them. On the other, the people elect and delight in corrupt, selfish and, sometimes, what looks like stark mad people.

You know, under former governor Martin Wambora, we thought Embu was nasty. That was before we discovered the ‘stirrers’. Thank God for those leaders who restore our faith in humanity.