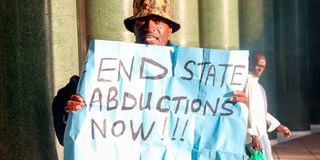

Activist Julius Kamau holds a placard reading “End State Abductions Now” as he protests along Kimathi Street in Nairobi on December 28, 2024. His demonstration aims to raise awareness about human rights abuses and demand accountability from government authorities.

Abduction or kidnapping as a strategy of informal repression is an existential threat to democracy in the 21st century.

We are facing a global kidnapping epidemic. According to United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, more than 59,000 people have been victims of abductions or enforced disappearances across 110 countries since 1980. As of January 2025, over 46,000 cases of enforced or involuntary disappearances are still unresolved.

Closer home, politically-motivated abduction — classified under international law both as a war crime and as a crime against humanity — is increasingly becoming an existential threat to Kenya’s fragile democracy. According to a “State of National Security report” tabled in Parliament by President William Ruto during his State of the Nation Address in 2024, between September 2022 and August 2024 a total of 88 Kenyans were victims of kidnappings or abductions.

In the same vein, the Kenya National Human Rights Commission, an autonomous institution established by the Kenyan law, reported that 82 Kenyans have gone missing between June and December 2024. While many of the people reported later resurfaced and some found dead after the country's youth-led anti-tax protests in June last year, as of January 2025, some 29 abducted Kenyans are reportedly missing.

Conceptually, kidnapping is a Janus-faced problem. One face is the abduction of people. The other face, largely metaphorical and a more serious and insidious security threat, is the kidnapping of democracy itself! The two faces of abduction may be different, but they are inextricably fused.

Abduction

The two faces of abduction have fuelled the “Kidnapped Democracy” thesis. Polemically speaking, the idea of kidnapped democracy is a powerful metaphor that at once connects and contrasts the abduction of the people with the kidnapping of the institutions of democracy by elite minorities and their accomplices.

The “kidnapped democracy” thesis uses ‘captivity’ to illustrate the connection between the abduction of citizens and the hijacking of a political system. “Captured Democracies”, argues a report by Oxfam International (2018), is a government of the few by the few for the few. The Spanish scholar, Ramon Feenstra makes the same point in his polemical book, “Kidnapped Democracy” (2019). The book is tour de force, observing that powerful elites have tragically captured the decision-making processes to serve their own interests rather than those of the majority.

But who, exactly, are democracy’s kidnappers? As in conventional kidnapping, a kidnapped democracy has its stakeholders including the kidnappers, their accomplices, the kidnapped and negotiators. From the Nazis in the 1930s-1940s hiatus to the military Juntas in Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1960-1980s decades, the use of enforced disappearances as a state practice has morphed into a global challenge. Kidnapping is an informal repression strategy widely used by governments to contain political opponents and quell popular protests. In theaters of internal conflicts, non-state actors such as organized groups, terrorists and pirates also commonly carry out abductions and contribute to holding democracy hostage.

Democracies are also taken hostage by powerful financial forces. Unable to resist the pressure of economic power or to defend the interests of their people, the elite at the helm of hostage democracies kowtow to the hidden hand of foreign influence. Government cannot really act freely. Instead, they kowtow to the interests of powerful external governments and elites at the apex of their multinational corporations, foundations and development agencies. Since 2023, Kenya has prioritized repaying its public debt with taxes, which has turned annual budgets into triggers of popular resistance.

Related to the kidnapping of democracy is the prevalent misuse of digital tools and social media to sway public opinion, skew elections to ensure that a pliant elite captures or retains power. Cambridge Analytica has been suspected of swaying political campaigns around the world, including presidential elections in the US.

Kidnapped democracies

Democracy is a sitting duck for kidnappers, revealing the inability of governments to protect their own citizens from its security agencies or organized groups using abductions to gain publicity, trigger civil unrest; force the release of group members arrested, gain ransom or resources to fund the causes.

Hostages in kidnapped democracies are diverse. In kidnapped democracies, parliaments, judiciaries, executives, political parties, opposition, trade unions, mass media, NGOs, governance structures of ethnic groups and other political institutions are held hostage, unable to function freely.

In a sense, a new political culture of forging mongrel “grand coalition”, “handshake” or “broad-based” ‘power-sharing' governments after elections has hijacked and weakened the opposition in Kenya. The post-election kidnapping of democracy in Kenya carries all the traits and effect of the Stockholm syndrome, a coping mechanism by the abducted to a captive or abusive situation. After elections, like hostages who develop positive feelings toward their captors or abusers over time, Kenya’s opposition elite use the lexicon of forging “national unity” to sanitize their own captivity and that of the country’s democracy.

The consequences of the kidnapping of democracy are dire. It has led to widespread citizen disaffection, indignation and protests. Democratic institutions have become less legitimate. They exist not only to serve a very tiny minority.

The big question remains: how can democracy be released and freed from its kidnappers? The answer partly lies in the implementation of the letter and spirit of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPED) which came into force in 2010. Kenya signed the treaty in February 2007. But because Nairobi has not ratified the Convention, it is not legally binding in the country. Laudably, President William Ruto's government established a Multi-Agency Taskforce on Extrajudicial Killings and Enforced Disappearances in 2023. This marks a significant milestone towards ratifying the Convention.

Professor Peter Kagwanja is the Chief Executive at the Africa Policy Institute and the Co-Author of Kenya's Uncertain Democracy: The Electoral Crisis of 2008 (London: Routledge, 2010).