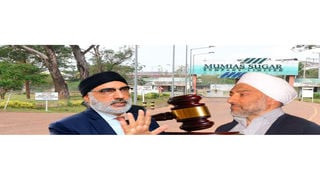

Billionaire brothers Jaswant Singh Rai (left) who operates from West Kenya Sugar, and his Uganda-based sibling, Sarbjit Singh Rai of Sarai Group.

| File | Nation Media GroupCompanies

Premium

How P.V Rao blunder on lease opened Mumias Sugar Company to court cases

Movenpick Hotel, Nairobi. October 6, 2021: It was at 3 pm. The Mumias Sugar Receiver Manager and Administrator, P.V. Rao, had called all the eight bidders who had sought to lease the indebted Western Kenya-based factory that had defied all resuscitation strategies.

Mumias, partly owned by the government, had been placed in receivership by KCB, where the government is still the largest shareholder. The court had also ordered the receiver manager to double as the administrator — the first time that had happened.

In the bid were two billionaire brothers, Jaswant Singh Rai- who operates from West Kenya Sugar, and his Uganda-based sibling, Sarbjit Singh Rai of Sarai Group. The two brothers— who fell out a few years back — straddle the East African sugar sector like age-old suikerlords. Their diversified investments run into billions of shillings and sugar sweetens their fortunes. Occasionally, they – like most billionaires – seek political protection.

The Mumias receivership had placed on the table one of the largest sugar mills in the region – and any successful bidder would take the factory, the nuclear estate and thousands of frustrated farmers.

On the day the bidders' financial proposals were disclosed, the receiver made a major mistake unheard of in bidding history: He picked the lowest bidder. This move would later open new court battles — between the two billionaire brothers — that set back the intended transformation of Mumias Sugar.

It was unclear why Mr Rao rejected the highest bidders and opted for the lowest bidder, Sarrai Group. But that opened the war between the two billionaire brothers. When the matter went to court, Rao accused the other bidders of "sensationalising the figures alone."

It is these court cases that President Ruto was alluding to as he ordered all the interested parties to vacate the company, drop the cases, or move out of the country, or go to heaven. “This is a public company,” said the president.

Rao had told Justice Alfred Mabeya that he wanted Mumias Sugar to be "offered to a safe pair of hands." His argument was that leasing Mumias to Jaswant Singh Rai would have made West Kenya Sugar Company control 41.95 per cent of Kenya's total sugarcane capacity per day. Thus, he picked Sarrai Group of Uganda. The paradox was that while West Kenya had bid a total of Sh36 billion for a 20-year lease, Sarrai Group had offered a fraction of that — Sh5.84 billion.

Mumias Sugar Company in Western Kenya.

More so, West Kenya's six-month lease deposit was 34 per cent of total KCB Group debt or Sh900 million compared to four per cent by Sarrai Group, equivalent to Sh117 million.

After an uproar over the hand-over of Mumias to the lowest bidder, Rao sent a statement dated December 22, 2021: "Although the lessee is not in sugar production in Kenya, it has a proven track record of running three sugar factories, a distillery, and power generation in Uganda and is committed to commence rehabilitation of assets immediately to ensure revival of operations within the shortest period."

When the matter went to court, West Kenya claimed before Justice Alfred Mabeya that Rao had disqualified it because of its success in the sugar sector.

On its suitability, it claimed to be one of the oldest sugar mills in Western Kenya and that it had more than 80,000 contracted farmers and over 49,000 Ha of land under cultivation. Further, it claimed to have a majority stake in Kinyara Sugar Limited, Uganda's second-largest sugar company.

The receiver explained that he rejected West Kenya's Sh36 billion to avoid West Kenya's monopoly and on account that the bidder, Jaswant Rai, was a competitor of Mumias.

The receiver further argued that had West Kenya company gotten the lease; it would have become a "dominant player" in the sugar sector contrary to competition laws.

But West Kenya lawyers argued that only the Competition Authority, and not the receiver, was mandated to determine a "dominant player."

The receiver also claimed that West Kenya had no financial capability to execute the lease and that it was a spoiler bid.

He said he was also unconvinced that West Kenya could afford to pay Mumias Sh150 million monthly or the stated offer of Sh 1.8 billion per annum.

In his ruling, Justice Mabeya agreed with West Kenya Sugar's lawyer that the receiver inordinately usurped the powers of the Competition Authority and that he was not the right person to determine the dominant player.

Rao had also eliminated bids from Transmara Sugar, Tumaz and Tumaz Enterprises, and Kruman Finances. Finally, only five bids were left: Devki Group, West Kenya Sugar Company, Kibos Sugar, Sarrai Group and Pandhal Industries. But these were not considered, too, though their bids were higher than Sarrai Group.

On December 22, 2021, three days to the Christmas holiday, Rao handed the Mumias Company to Sarrai Group's chairman Sarbjit Rai.

The previous day, Sarrai Group had paid Sh69.6 million as a security deposit. The lease was for a renewable 20-year term for all properties with legal rights and claims. For the first year, Sarrai Group was to pay Mumias Sh58 million – meaning it would lease the facility for a monthly fee of Sh4.8 million for the first year.

Loaders hang on to a tractor transporting sugarcane to Mumias Sugar Factory in February 2018.

It was a pittance compared to West Kenya's promised investment of Sh4.5 billion to rehabilitate the nucleus estate and overhaul the machinery.

"Our main objective for the leasing and operations of the Mumias Sugar assets is to facilitate a quick turnaround of the mill operations and to provide employment opportunities to the people of the Mumias region, as well as creating a ready market for the out-growers cane. This shall in turn improve the living standards of the population within the region." They had said in their bid.

Rao admitted in court that he did not mention the amount of money Sarrai Group was offering compared to the competitors during the opening of the bids.

In his affidavit dated January 12, 2022, Rao explained why he did not evaluate the bids: The "court orders in place at that time allowed me to proceed with the bid opening but restrained me from evaluating or taking action on the bids." Rao claimed that "comparing the bids" would amount to evaluating the bids, which would contravene the court orders.

As the cases against Rao's decisions in Mumias mounted, Justice Mabeya made a landmark ruling on how Mumias Sugar Company should be salvaged from its death.

The judge not only removed Receiver Rao from the administration of Mumias Sugar but also separated the receivership from the administration.

Secondly, he nullified, revoked and cancelled the Mumias' Lease to Sarrai Group entered on December 22, 2021, and ordered them to vacate the premises. He further appointed Kerento Marima of K.R. Consult Ltd as the new Administrator of Mumias.

But Sarrai Group did not leave – they fought back.

While Justice Mabeya had further ordered the receiver manager to cooperate with Kereto Marima and ensure the smooth administration of Mumias, the battles between the two brothers intensified through proxies.

Failure to cooperate, Mabeya said, "the receivership shall stand suspended during the duration of the administration." He also prohibited Victoria Commercial Bank, Ecobank, and Propaco from appointing Mr. Harveen Gadhoke "or any other person" as receiver manager over the assets of Mumias during the pendency of the receivership and/or administration.”

The case was seen as a landmark for it argued on the supremacy of public interest. "Public interest commands that Mumias survives and is rescued…That its machinery and equipment should roar back to life. That smoke should start billowing from the chimneys of its machinery. That the farmers who are owed millions get paid their dues and others plant sugar cane for future survival."

Justice Mabeya held that the leasing process of Mumias Sugar Factory to Sarrai Group was flawed and that Rao's conduct concerning the leasing process "demonstrated a lack of integrity, competence, a conflict of interest, a lack of fidelity, and did not adhere to the mandatory provisions of the law."

Finally, he found that Sarrai's lease on Mumias - on an average monthly rent of Sh19.5 million for the 20 years- was not commensurate with the asset.

He concluded that Rao's decision to award the lease to the lowest bidder was shrouded in "opaqueness, financial non-viability, and fraud" and that "Rao had demonstrated incompetence and conflict of interest".

He said that Rao was conflicted in his administrator and receiver positions, and which explained why he appealed for his appointment as an administrator.

In the landmark finding, Justice Mabeya for the first time experimented with Canadian jurisprudence on a successful administration.

The court held that administration was the "kiss of life" while "receivership" was the "kiss of death" and that it hoped that Rao would balance between the two.

Justice Mabele said: "The Insolvency Act was enacted to give a kiss of life to financially distressed companies. It introduced the notion of public interest. The objectives set out in section 522 are the guiding spirit of any administration. That is the route Rao and KCB want to run from."

"If Rao found it difficult to juggle the two hats he had been bestowed with, he should have come back to court to seek directions. The court which had appointed him to double as both administrator and receiver was not short of wisdom on what was to be done," said Justice Mabeya.

"Mr. Rao was simply running away from his responsibility as an administrator and decided to run away with receivership by which he would act with impunity. That won't do."

In essence, the court was accusing Rao of leasing the Mumias assets to the Sarrai Group as a receiver manager and not as an administrator.

Rao contended that he found himself in a sui generis (a unique) position. He argued that this was the first time in Kenya that one was required to combine the duties of an administrator and receiver.

But Rao was told by the judge that under the Insolvency Act, "every decision must be made in the best interest of that company…. The receivers' duty and loyalty goes beyond the debenture holder who appoints him as such or as receiver. He must undertake his role in a manner that promotes the company as a going concern, where possible, to enable it to repay its debts and be discharged from administration and receivership."

The court felt that Rao had duped it. "This court believed Rao when he stated that the only process to revive Mumias was through the leasing of its assets; getting a strategic partner who was willing to pump in enough capital to operationalise Mumias… [But] Was the resultant lease in the best interest of Mumias and the entire body of creditors?"

The answer was No.

[email protected] @johnkamau1

Tomorrow: How Mumias was derailed by litigants