Business

Premium

How inflation has wreaked havoc on poor households over a decade

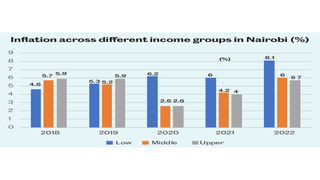

The runaway cost of living has been relentless and is wreaking havoc in Kenya given that higher prices erode the value of real wages and savings leaving households poorer. But these effects are not felt equally with the poor and middle class bearing the brunt—reflecting the composition of their income, assets, and consumption baskets.

An analysis of price changes for 26 consumer items by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) over the last 10 years shows that the country’s wealthy have remained largely unscathed by inflationary pressures.

A spike in prices of basic commodities culminated in street protests in the first half of this year, as the economy was battered by a debilitating drought, a weak shilling, and global supply constraints due to the war pitting Russia and Ukraine.

Food items—which take up a larger space in the shopping basket of the poor—were hit the hardest by an increase in prices. KNBS categorises the lower middle-income group as households in Nairobi with a monthly income of up to Sh46,355 per month.

The middle class has a monthly income of between Sh46,356 and Sh184,394 in Nairobi while the rich constitute households with incomes above Sh185,395.

In the period between 2013 and last year, the prices of these items increased by an average of 41.6 per cent, hitting the poorest the hardest.

Analysis of the data from the national statistician reveals that for every Sh1,000 that the poor spend in a given period, these items will take Sh219, twice as much as the Sh113 that the rich will spend on these products.

The middle class, on the other end, will spend only Sh149.

Stellar Swakei, a senior research and investment analyst at Standard Investment Bank says the fact a bigger space in the poor people’s shopping basket is occupied by essential items means that they are the most vulnerable to the impact of inflation.

A customer picks fruits at a supermarket in Nyeri.

“As prices rise over time, it disproportionately them (the poor) as they allocate a larger portion of their income to necessities, mostly food,” said Swakei.

Furthermore, items such as maize flour with high demand and which constitute staples for most low-income homes, tend to be impacted highly by the dynamics of demand and supply, added Swakei.

“In contrast, middle-income households possess a marginally greater capacity for diversification, while upper-income households enjoy the latitude to make choices and embrace a more opulent lifestyle,” added Swakei.

The consumer price index (CPI)—the cost of living measure used to compute inflation—shows that a big chunk of cash for the wealthy goes into non-food items.

These items that take most of the cash for the rich include rent for their three-bedroom houses, furnishing their homes, and having a retinue of domestic servants on call. They also tend to spend more on home internet.

Kenya’s affluent, the KNBS data shows, also spend their money buying, fueling, maintaining, and insuring their cars. Dining and wining in restaurants and high-end hotels and taking international flights are the other notable expenditure items for the wealthy in Kenya, according to data from the national statistician.

For every Sh1,000 that the rich spend in a given period, at least Sh690 goes into these items, which are not among the items whose prices have increased by a high rate in the review period.

Some of these items include grade two rice whose price nearly tripled from an average of Sh102.2 per kilogramme in 2013 to Sh303.83 last year.

Others include 500 grammes of margarine which increased by 69.5 per cent in the review period. A kilogramme of English Potatoes rose by 61.6 per cent, maize loose grain (by 60.1 per cent) while 400 grammes of cooking fat went up by 58.5 per cent).

A 500 ml can of Tusker has increased by an average of 56 per cent, a litre of kerosene by 51.4 per cent, a kilogramme of beef with bones (50.1 per cent), a unit of dry beans (49.2 per cent), matumbo (45.3 per cent).

Over time, the only constant has been the loss of purchasing power, not just for low-income groups but the high-end groups as well, said Ronny Chokaa, senior research analyst at AIB-AXYS Africa, an investment bank.

“What makes the difference is that the high-income earners have a high ability to consume out of their incomes without a reduction in their living standards, while the low-income earners tend to spend a high proportion of their income on necessities, especially food,” said Chokaa.

Analysts agree that since poor peoples’ revenues have been going into staples susceptible to price hikes, this has limited their ability to save or invest in wealth-building opportunities. This means they are always living hand to mouth.

“This cycle makes it challenging for individuals in the low-income group to accumulate assets and improve their financial standing over time,” said Swakei.

Mr Chokaa noted that since the rich tend to spend proportionally less out of their total incomes, they have more avenues to invest.

“As such they are able to keep, or at least offset, the increase in the cost of living. What this has done is that it actually widens the inequality between income groups,” said Chokaa.

KNBS data showed that the gap between Kenya’s richest and poorest widened after a dip during the peak of the coronavirus pandemic, with the wealthiest taking home a record share of the nation’s income.

Income inequality rose to 38.9 per cent in 2021, from 35.8 per cent a year earlier, according to the National Statistician.

This is measured by the Gini coefficient, which varies from 0 per cent in cases of perfect equality to 100 per cent in the most unequal distribution.

Indeed, the kind of investments the affluent make, aided by seasoned investment bankers, are tailored towards hedging against inflation.

“When we think of the years ahead, we must factor in inflation,” said Paul Njoki, head of Affluent Banking and Wealth Management, at Standard Chartered where he handles high-net-worth individuals.

“For example, if you are saving for your children's college in five years, you must consider the likely increases in fees and cost of living, or else your savings will fall short,” added Njoki.

There is a need for policy-makers to put in place a macro-economic environment that will ensure a steady supply of food to stabilise prices, reduce poverty, and improve the living standards for the majority poor.

As part of its goal of agricultural transformation, the administration of President William Ruto intends to spur production by addressing the cost, quality, and availability of inputs.

It also intends to increase production by providing farmers with working capital to buy an adequate supply of the inputs like cheap fertiliser as well as other direct production expenses such as ploughing of land and labour.