From left: Paul Koigi (Shankido), David Igogo (Gogos Juma), Dennis Njoroge (Masilver), Peter Mwangi (Miracle aby) and Alexander Ikuro (Lexxy Yung) members of Sailors Gang of the hit single Wamlambez pose for a photo on September 21, 2019.

| File | Nation Media GroupShowbiz

Premium

In Gengetone, Wasafi finally meets its match

Like most things in life, the Kenyan urban music scene has had its fair share of ups and downs.

Though Kenya ruled the African urban music airwaves in the late 1990s and early 2000s, other markets, such as Nigerian (Naija), Tanzanian (Bongo) and South African (Kwaito), have risen to dominate the local space.

Music evolution

Opinion varies on the current state of affairs, but it is clear Kenyan music has evolved to become a highly segmented market, with various tastes and preferences.

Except for Gengetone and some leading voices, foreign music continues to nibble away at the local artistes’ cake, nearly 20 years since the golden age of Kenyan urban music.

Grace Kerongo is one of Kenya’s showbiz editors with more than two decades of experience watching the entertainment scene.

In her view, the emergence of the late E-sir, Nameless and Gidigidi-Majimaji marked the golden era of urban music, when Kenya was way ahead of its rivals in Tanzania and Uganda.

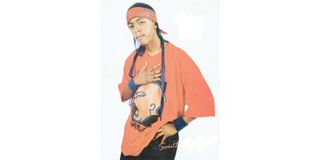

E-Sir. He is remembered for hit songs including Moss Moss, Saree, Kamata, Leo Ni Leo, Maisha and the electric Bomba Train.

Though South Africa and Nigeria back then presented a formidable challenge, they did not make major inroads till around 2004-2005, when the likes of P-Square, 2Face Idibia and D'banj broke into the local scene.

In contrast, the Kenyan performers did not venture out into those markets and so foreign music began to seep into the country.

In the larger East Africa, only Congolese music was big, but it was limited to the older crowds who had loved it from their youthful days.

Awilo Longomba was perhaps the only Congolese artiste who appealed to the youth and inspired a whole new generation of urban African artistes.

Congolese lingala maestro Awilo Logomba and his band on stage during in Nairobi on November 27, 2016.

At the time, the rest of East Africa was still developing its urban music; in Tanzania, only Professor Jay and later Mr Nice were making headway.

Mr Nice.

In Uganda, traditional music dominated until Chameleon returned home from Kenya with a brand new sound of Luganda-dancehall that has defined music there for decades now.

“We used to be the SI unit of urban music back in the day, other countries learnt from us and mastered it,” Grace Kerongo explains.

“Diamond took a bus from Tanzania just to sing with P-Unit for the MAMA’s and he would hustle for interviews from Kenyan media. P-Unit were actually offended when they were paired with a then-upcoming artiste, Diamond, who was looking skinny and scrappy then, but look where he is today.”

Stagnation of Kenyan artistes

According to her, the stagnation happened because Kenyans became complacent in their craft and efforts to push their brand.

For her, talent is just 1 per cent while management, marketing, branding and PR are 99 per cent.

Though the local scene is flooded with talent, most acts lack the organisational structure to make big moves. She holds that Bongo, Naija and South African artistes and their teams are extremely aggressive when it comes to pushing their content and brand.

Rapper Sylvia Ssaru commonly known by her stage name Ssaru Wa Manyaru.

“There are local artistes that I call for interviews and it takes forever for them to respond, yet we have foreign acts who are stalking Kenyan journalists in their emails. We don’t appreciate the power of media in the Kenyan industry, that’s why we are struggling,” she opines.

A key reason for the golden period was the proliferation of the FM stations that peaked in the early 2000s, expanding the variety of music that listeners were exposed to. At the time, revellers would dress up and pay top dollar at prime locations such as Carnivore and flock concerts filling up stadiums in some cases.

And renowned events organiser Chris Kirwa knows this all too well.

“We did an event in the early 2000s dubbed Metro Extravaganza by Metro Fm and we got well over 60,000 people in attendance. That was the largest number of people I have ever seen in all my years of organising events in Kenya,” explains Kirwa. “These days we have to work extra hard to get 10,000 at a gig.”

The show had 100 per cent Kenyan line-up consisting of the likes of Prince Julie, Poxy Pressure, Kalamashaka and all the top acts of that era.

The Kalamashaka trio of Johny, Roba and Kama.

Around the same time, he organised a show for Gregory Isaacs at the Carnivore and got around 25,000 people. He holds that things started to take a turn for the worse around 2010 due to increased variety, which saw the audience develop various tastes.

Cheaper alternatives

The mushrooming of pubs in estates also provided cheaper alternatives for entertainment, with many preferring to visit their local pub instead of attending a big concert.

Other factors that have contributed to lower concert turnout include affordability for the low-end market, a lack of interest among the middle-class and an upper-class that prefers to fly out to South Africa and other countries for A-list concerts.

“This situation is unique to Kenya. We are addicted to complimentary tickets and we actually take pride in getting things for free,” he admits.

"Some of our premiere festivals only get 4,000 people and out of that 1,000 are vendors another 1,000 are sponsors, so only 2,000 are paying.”

At the turn of the decade, as secular music was declining, the gospel scene began to take root and dominate the local airwaves, largely due to Groove Awards, which began in 2009. Gospel Urban radio show Kubamba on Metro FM had introduced audiences to a modern version of the genre in the early 2000s and has grown with the sub-sector over the years.

Starting out with the likes of Rufftone, Henrie Mutuku and Kanji Mbugua, Kenyan gospel music grew in leaps and bounds.

Gospel singer Henri Mutuku.

By 2010, it was so big that Daddy Owen won the MAMA’s with almost no equal in any other African country.

“When I won the MAMA’s in 2010, I was supposed to do a collabo with an African artiste. Unfortunately, no one was big enough in other countries,” Daddy Owen explained during a recent YouTube interview with comedian Jalang'o.

Genge

Over the years, hardcore hip hop has evolved and remained resilient despite the incursion by foreign acts. Jua Cali and Nonini were the pioneers of the Genge sound, a genre that has been associated with Clemo’s record label, Calif Records.

Jua Cali performs with a band in Nairobi on January 16, 2020.

Initially considered an Eastlands sound, it eventually rose from the underground to the mainstream. And though among the larger audience it struggled to gain traction, its core fans have remained loyal from day one. Similarly, the current Gengetone wave that hit the country a few years ago has kept up its pace, continually capturing Kenyans’ imagination.

“To be honest, I am tired of this story of constantly reminiscing about the good old days,” Jua Cali says. Everyone thinks the music from their era is the best; our parents had Zilizopendwa, we have our classics and 20 years from now, these kids will be talking about music from our time in the same way.”

Gengetone

Jua Cali argues that the Kenyan music space has always been segmented, with Genge serving up hot bangers from back in the day and Gengetone picking up from it. In his view, artistes don’t have to venture out of Kenya to make it in music because “no matter how big one becomes, their home ground remains their key support”.

Whether as part of underground hip hop or a breakthrough sound, Genge sound and its offshoot, Gengetone, have been a major part of the Kenyan music scene for the past 20 years. The fact that Jua Cali remains one of the most relevant Kenyan artistes, receiving massive acclaim across the country, attests to the resilience of his genre.

“We are not ice cream; we can’t be loved by everyone. We have our fan base that has kept up with us all these years. The rest of the people I don’t care about. As long as you have not paid something to come watch me perform live all these years, then your opinion doesn’t hold water.”

Deep sheng lyrics

Some of the drastic changes he has seen in the industry include the proliferation of technology, which has changed how music is made, packaged, distributed and discovered.

Nonetheless, the veteran rapper holds that some fundamentals of the industry remain the same. He estimates that it still takes about seven years for an artiste to establish themselves.

He argues that a professional takes about four years in college and another three working in their field before they can make it. And music is no different.

Luminaries of the Gengetone wave, Mbogi Genje, have invigorated the space with their deep sheng lyrics.

From left: Anthony Odhiambo (Smady Tings), Teddy Ochieng (Guzman) and Malaak Dave (Militan Govana) of Mbogi Genje group in Umoja on January 26, 2021.

So twisted is their version of slang that most Kenyans don’t even understand what they are saying, a fact that has endeared them to listeners who are curious to find out more. This language barrier has had the odd effect of masking their otherwise lewd lyrics, making it palatable to the masses.

“People can’t get offended by your songs if they don’t understand what you are saying,” Smady Tings of Mbogi Genje explains.

“It’s a trick Diamond and many artistes have used for many years; you have to use hidden language when talking about certain things. Those who can understand will understand but those who can’t will just enjoy the song.”

Just like its predecessor, Gengetone is loved by its core fan base, hated by the moralists and enjoyed by the masses. It reinvigorated the Kenyan sound, giving the country a musical export to the world while giving foreign music a run for its money in the local scene.

Its raw and unadulterated expression of downtown Nairobi life continues to capture the imagination of the youth and the curiosity of the general public.

Freestyles

“Most of our songs come from freestyles that we develop as we are chilling in the hood,” he adds. "We aimed to bring something new to the music space and I believe we have done that.”

As for the current state of affairs, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact lay of the land in this playlist era. With listeners discovering music from all sources and curating their playlists on their preferred apps, the musical pallet has become diverse.

Markets are so highly segmented that DJs and TV and radio programme managers have to do a lot of research to curate music that fits the audiences they are dealing with. Gone are the days when a DJ would play the role of tastemaker; this is the age of reading the crowd and playing what they want.

Naijainvasion

DJ Joe Mfalme is one of the top scratch masters in the country, playing in top clubs, TV and radio shows.

By the time he was joining the industry, the current Naijainvasion – take of Kenyan airwaves by Nigerian artists – was well underway. But in his stay, he has seen Kenyan artistes mount a substantial pushback.

“Right now Kenyan music is actually doing very well. I can say about 60 per cent of my playlist is Kenyan music. This, however, varies depending on my crowd. The 18-25 crowd wants 90 per cent Kenyan music while the out-of-town crowd want 100 per cent Kenyan music."

This he attributes to the likes of Khaligraph, Fena, Mejja, Nikita Kering, and Cathy Matete who continue to churn out quality music, consistently.

Reggae artist Cathy Matete during a past event.

He predicts that the new crop of artistes and those who are following hot on their heels can rule Africa if they play their card right.