SHIF mess: How transition to new healthcare system was bungled

Clients walk towards the newly rebranded Social Health Authority(SHA) building on October 1, 2024, as the government officially rolled out the healthcare service provider.

What you need to know:

- Healthcare providers were unsure about how they would be paid under SHA.

- The new healthcare system was marred by legal challenges, including court orders.

A rushed system that failed test runs, failure to consult interest groups, poor benefits and late signing of contracts with medical facilities are missteps by the Ministry of Health that led to the chaotic launch of the Social Health Authority (SHA) last week.

The SHA, which replaced the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) on October 1 after nearly six decades of operation, was supposed to provide better health services, broader access and greater efficiency, but its rocky start has been painful for patients.

In addition, the chairman of the National Assembly's health committee, Robert Pukose, had cautioned against the hasty rollout of the Sh104.8 billion Integrated Health Information Technology system, noting that it had failed test runs in Marsabit and Tharaka Nithi counties.

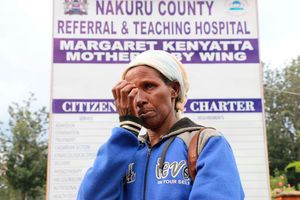

Patients with chronic conditions such as kidney disease and cancer, who rely on regular dialysis and oncology treatments, have been particularly hard hit by the chaotic transition.

In some hospitals, patients have been turned away because their names were not on the SHA system and they did not have the cash to pay for treatment.

One patient, John*, who has been undergoing dialysis for years under NHIF shared his frustration.

“I don’t understand why I suddenly can’t get treatment. I’ve been registered for years, but now they say I have to register again. Meanwhile, my condition can’t wait for this kind of bureaucracy," he lamented.

Similarly, Jane*, a mother of two who was undergoing cancer treatment, was left stranded because the hospital could not access her records in the new system.

"It is as if my name has been erased from the system. Do I have to register every day I come for services? Why can't someone explain to us what this is all about? My life depends on chemotherapy. I missed my sessions on Monday and Tuesday. Today (Friday) the treatment continues as if nothing had happened. What happened to the sessions I missed?" she asked.

Global trends

The idea of SHA is in line with global trends and best practices in health financing. Many countries have adopted social health insurance models to provide Universal Health Coverage (UHC), with notable examples in Europe such as Germany and France, and in developing countries such as Rwanda.

These systems collect resources from both the government and citizens based on income, ensuring that wealthier citizens contribute more while vulnerable groups are subsidised by the state.

In Kenya, the idea for SHA was born as part of a wider health system reform plan, based on recommendations from health experts, international bodies such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) and successful examples of social health schemes in countries with similar socio-economic conditions.

The blueprint for SHA was also driven by lessons learned from the challenges and failures of NHIF with the new system aiming to be more transparent, efficient, and inclusive, offering a more robust safety net for all Kenyans.

However, a week into its launch, numerous challenges including system glitches, resistance by service providers and public confusion have marred the transition.

Forcible registration and threats by the government have raised questions about the new system. But how did a transition that was meant to be smooth sailing end up in crises witnessed in public hospitals across the country?

Healthcare providers were unsure about how they would be paid under SHA and the government’s failure to provide clarity on this matter created friction between service providers and the new system.

“We asked for a meeting immediately. This was gazetted so that we would work on the gaps. We opposed the implementation since it was going to disenfranchise civil servants and their dependents from access to health care, take away the right to health care and is in contravention of a collective bargaining agreement agreed upon by civil servants in 2011. No one listened to us,” said Dr Davji Atellah, Secretary General, Kenya Medical Practitioners Pharmacists and Dentists Union-KMPDU.

"SHIF is a capsizing ship! There is too much bilge water for it to sail. We have repudiated the Act from November 2023, with one message: it will deny Kenyans access to healthcare," he said.

The fact that NHIF, which SHIF was meant to replace, was riddled with corruption, mismanagement, and inefficiency should have been an indication that transitioning to a new system without addressing the root causes of NHIF’s failure would likely lead to similar problems.

“While SHA promised transparency and accountability, many feared that without systemic reforms, the same issues of fraud, slow payments, and misappropriation would persist under a new name,” Dr Atellah said.

He added: “The longstanding public distrust in NHIF should have been a clear sign that rolling out a new healthcare system required not just a change in structure but also in governance and operational integrity.”

The new healthcare system was marred by legal challenges, including court orders stopping its implementation which also raised concerns about the legitimacy of the public participation process.

The law that established SHA faced resistance from civil society groups, healthcare stakeholders, and even members of the public. The public participation process appeared rushed and insufficient, with many claiming they did not have an adequate opportunity to weigh in on the reforms.

The court's involvement and civil society protests should have been red flags that the system’s implementation might encounter strong opposition, but these concerns were largely downplayed.

Questions have been raised too about limited benefits under SHA despite far higher premiums.

Sh1,700

Under NHIF, the maximum contribution was Sh1,700 but SHA introduced a 2.75 per cent payroll deduction for formal sector workers and sought to create a larger pool of funds.

According to the government, NHIF’s flat rate contributions were insufficient to finance the long-term healthcare needs of a growing Kenyan population.

Dr Vitalis Ogolla, dentist and a service provider under the former NHIF, questioned whether the government has the interests of Kenyans at heart.

“I am sure the majority know someone who has been diagnosed with cancer. I don’t see the health officials talking about coordinated healthcare. This is about the money and not the service,” Dr Ogolla argued.

“For the dental, I can bet that with the Sh650 SHA proposal for extraction, no facility can operate with such an amount. This is even below the input cost. Does it mean that the government wants to enslave us in terms of payment? No facility will accept this, and facilities will be forced to operate without a cover,” Dr Ogolla said.

Dialysis providers have also indicated that they will only transition to SHA after their outstanding payments of Sh10 billion are settled and SHA reviews rates they consider as too low.

The group has said that the current rates being proposed by SHA do not align with market conditions, leaving many service providers drowning in debt.

“We have worked closely with NHIF for over two decades to provide quality health care for patients with kidney disease. However, we are deeply concerned by the NHIF's failure to readjust the reimbursement rate to match the market condition and to fully remit claims,” said Dr Jonathan Wala, chairman, Kenya Renan Association.

According to Dr Ogolla, the Sh104 billion that the government was spending on a new ICT system introduced under SHA, a massive leap from the Sh700 million required if the country had upgraded the existing NHIF ICT infrastructure, was enough to build about six new referral hospitals across the country.

“This is enough to tell you that this project is for a few who are out to loot money and not for the benefit of Kenyans. They should be ashamed,” Dr Ogolla said.

“Even before the registration was launched, no one was willing to explain to Kenyans what this was about. The only thing they knew was the deduction of 2.75 per cent. A number to date are not aware of what the transition meant for their existing NHIF coverage. The government’s failure to conduct effective public education and outreach left many in confusion, with many citizens refusing to migrate from NHIF and being forced to register anew under SHA,” Dr Atellah said.

On October 19, 2023, while assenting to the Social Health Insurance Act 2023, President Ruto indicated that the new plan was a game changer.

On November 22, 2023, the then Health Cabinet Secretary, Susan Nakhumicha, gazetted the Act which made it mandatory for adult Kenyans and foreigners residing in the country to register for SHIF.

Section 26 (5) of the Act makes it mandatory for registration of the SHIF and directs the central and regional governments to deny services to non-members.

“A person who is registrable as a member under this Act shall produce proof of … registration and contribution as a precondition of dealing with or accessing public services from the national government, country government or national or county government entity,” the law states.

On November 23, 2023, President William Ruto appointed Dr Timothy Olweny to be the non-executive chairman of the SHA board for three years. He was joined by Dr Zakayo Gichuki representing the Kenya Medical Association (KMA), Ms Jecinta Mutegi, on behalf of health care service providers and Central Organisation of Trade Unions Secretary-General Francis Atwoli.

“Just two days before the official launch of SHA, the Chairman of the Social Health Authority was replaced, disrupting leadership at a critical time. This late change raised concerns about the stability and preparedness of SHA’s governance structure. Such a significant reshuffle so close to launch should have been a warning sign about the readiness of the system and the internal challenges it faced,” Dr Atellah said.

Queries have arisen on the readiness of the new system and its capacity with hospitals that have to offer services being left without access to the SHA system, many patients’ names missing, and challenges with claims processing during the first few days of operation.

An administrator in one of the leading hospitals in Nairobi said they have been kept in the dark since the beginning of the rollout of the system.

"We have no guidance or support from the authorities. Nothing is happening in the system and we are forced just to look at patients when they come for treatment," she revealed.

Hospitals only signed contracts with the Ministry of Health last week when the new system was already in place yet they were expected to offer services as normal.

“Who was going to pay for the services before the contracts were signed? Who were we going to bill for the services,” she asked.

The Ministry of Health has announced that the SHA system is fully operational with ongoing training for healthcare facilities on how to use the claims portal.

Already, about 1,442 private health facilities have been contracted, 4760 public hospitals with 51 cancer care health care providers and over 100 renal care facilities to be offering the services.

"We are pleased to confirm that the SHA claims system is now fully functional. Training for health facilities on the claim portal has begun and will continue throughout the week," said Harry Kimtai, Principal Secretary, of the State Department for Medical Services.