Simple, low-cost innovation reducing maternal deaths; but where is it?

The plastic sheet, which the researchers have named Maternova’s calibrated obstetric drape, measures blood loss accurately during childbirth, enabling early PPH detection and treatment.

What you need to know:

- postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), according to the World Health Organization (WHO), accounts for 27 per cent of maternal deaths globally. More than half of these deaths occur within 24 hours after childbirth.

- The bleeding is due to either a placenta that is not expelled after birth or when the uterus fails to contract after delivery. Each year, about 14 million women experience PPH, resulting in 70,000 deaths.

- In Kenya, it is the leading cause of maternal mortality, accounting for 34 per cent.

Childbirth is a miraculous and transformative event, but it can also pose significant risks to a woman and her baby if complications are not handled fast.

Scientists have, however, come up with a simple intervention to detect and treat postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), a condition that, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), accounts for 27 per cent of maternal deaths globally. More than half of these deaths occur within 24 hours after childbirth.

The bleeding is due to either a placenta that is not expelled after birth or when the uterus fails to contract after delivery. Each year, about 14 million women experience PPH, resulting in 70,000 deaths. In Kenya, it is the leading cause of maternal mortality, accounting for 34 per cent.

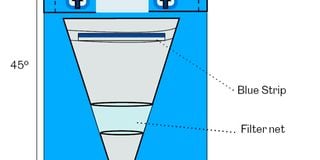

The plastic sheet, which the researchers have named Maternova’s calibrated obstetric drape, measures blood loss accurately during childbirth, enabling early PPH detection and treatment.

The “drape” has a funnel-like pouch attached to the bottom edge. It cuts life-threatening bleeding after vaginal births in hospitals by 60 per cent, according to the findings published in the New England Medical Journal.

The simple, low-cost and effective tool can save lives anywhere, from high-resource hospitals to remote clinics in low-resource settings. It costs less than R30 (Sh230) in South Africa. It is placed underneath the patient and tied around her waist after she has given birth. It collects blood in a pouch that hangs off the bottom end of the hospital bed, making it visible for healthcare providers to read the amount of blood being collected.

This helps the health providers to know whether the patient is bleeding more, triggering action and prevention. According to WHO, if a mother loses more than a litre of blood in the first 24 hours after giving birth vaginally, it is called postpartum haemorrhage.

Often, mothers die because health workers don’t notice early enough the amount of blood lost. However, with the drape, immediately the healthcare providers notice the mother bleeding, they deploy the treatments used in many health facilities to reduce severe bleeding. The drape where the blood is collected is marked and visible. The provider is to read if a mother has lost 300ml of blood in the first hour after birth. At 200ml, this is not considered postpartum haemorrhage, but they can start acting.

The two-year clinical research on PPH in Kenya was led by Prof Zahida Qureshi to investigate an effective way of diagnosing and treating the condition. “Late diagnosis and inefficient treatment of PPH are the main reasons women develop life-threatening complications after delivery, or even die,” Prof Qureshi said, adding that they intend to disseminate these findings to the public.

The large trial, led by the University of Birmingham in conjunction with the University of Nairobi, was carried out in 80 secondary-level hospitals across Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania. It involved 210,132 women who underwent vaginal delivery.

From the findings, postpartum haemorrhage was detected in 93 per cent of those in the intervention and in 51 per cent of those receiving usual care, and the treatment bundle was used in 91 per cent and 19 per cent, respectively. The drapes were assigned to only one group being investigated. The hospitals, rather than patients, were grouped into two.

Hospitals in the treatment group got drapes with volume markings to use during vaginal births. The placebo group hospitals used drapes without volume markings, with mothers getting usual care. The marked drapes helped the healthcare workers to catch instances of dangerous blood loss early so they could do something to help in time.

“The success of the drapes comes in when the healthcare workers are not guessing but able to tell the amount of blood that the patient has lost and immediately act,” says the report.

In the hospitals where the marked drapes were given, the nurses were trained to apply the five actions in the WHO-recommended list after noticing a mother suffering from PPH. In the placebo ones, they were not trained and were left to handle the mothers the usual way.

The study, dubbed E-motive, emphasised that immediately a healthcare worker notices bleeding, it should be followed by WHO’s five steps to stop it. First, check whether the blood pressure or heart rate is also dropping.

The actions should occur in an orderly manner. The quicker health workers step in the better the patient’s chances of surviving. Then, the nurse should give a minute-long uterus massage to help it contract and stop the bleeding, and administer Oxytocin, which also helps the uterus to contract, and Tranexamic acid, which promotes clotting.

Other treatments include IV fluids, which replace lost fluids from bleeding, and a thorough physical examination of the patient and birth canal. The other procedures follow if bleeding does not stop.

Dr Arri Coomarasamy, a gynaecologist at the University of Birmingham and an author of the report, said many women die because healthcare workers just gauge the amount of blood lost while not taking time to follow the steps. “It is the ticking of time that kills somebody who is bleeding,” Dr Coomarasamy said.

The five steps are already in Kenya’s guidelines on how to deal with PPH, although they are not always followed and at times the medicines are out of stock, hence increased deaths. According to Dr Coomarasamy, governments should adopt the innovation and consider making it available to hospitals to save lives.

Dr Coomarasamy has since been nominated for Officer of the Order of the British Empire and awarded the King’s Birthday Honours for his significant innovation that has led to the reduction of maternal deaths. “These innovative devices not only improve the quality of care but also empower healthcare providers with necessary tools to save lives. By embracing the findings of the trial, healthcare systems and policymakers can pave the way for improved maternal care on a global scale,” says the study.