Why it’s harder to detect and respond to zoonotic diseases

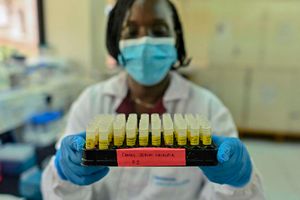

A veterinary officer vaccinates a dog against rabies in Mombasa County.

What you need to know:

- Changes in temperature, rainfall patterns and ecological conditions because of climate change affect the habitats of disease-carrying vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks, potentially expanding their range and increasing incidences of disease transmission.

- The most common animal species that are reservoirs for zoonotic diseases include non-human primates, bats, rodents, small carnivores, swine, rabbits, and dogs, so handling these animals needs great care.

Scientists in the East Africa region are concerned that scarce surveillance and reporting systems are making it harder to detect and respond to zoonotic disease outbreaks in a timely manner.

They highlight that zoonotic diseases often result in ill health and economic consequences associated with the illness, yet they are not taken seriously in many contexts.

The researchers highlight that inadequate collaboration and coordination between veterinary and public health authorities in the region is hindering effective disease control efforts.

The findings were published in a new peer reviewed study by TRAFFIC, a leading non-governmental organisation working to ensure that trade in wild species is legal and sustainable for the benefit of the planet and people.

“The diseases frequently occur in geographic locations where vulnerable groups live within marginalised communities that have limited access to health services. In some instances, developing countries deprioritise the needs of these communities, and they are not accorded sufficient attention,” they observe.

This is why zoonotic pathogens continue to emerge and spread across regions including East Africa and challenge public health by causing countless morbidities and mortalities, disrupting trade, and negatively impacting the economy in developing and developed countries, as it was the case during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The researchers warn that the emergence of novel pathogens from animal reservoirs due to certain changes in ecology increases opportunities for pathogens to enter the human population and could later result in transmission between humans.

“However, once this rare event occurs, then the subsequent transmission is maintained temporally or permanently, as exhibited by HIV, Ebola and the SARS coronavirus. On the other hand, pathogens such as lyssa viruses, Nipah virus, West Nile virus, Hantavirus, plague and leptospirosis are directly transmitted to humans from wild animals or through vectors and only rarely via human-to-human transmission.”

In East Africa, recent reported zoonotic disease outbreaks include the Marburg virus in Tanzania (March 2023) and Ebola in Uganda (January 2023).

These viruses are highly contagious and can cause severe illness, often with high mortality rates.

The reported leptospirosis outbreak in southern Tanzania is another contemporary example of zoonotic diseases of concern in the region, according to the experts.

“Over the years, the region has been struggling with a variety of zoonotic diseases, including rabies, brucellosis, anthrax, Rift Valley fever, bovine tuberculosis, porcine cysticercosis, African trypanosomiasis, salmonellosi, and borreliosis,” they highlight.

They further explain that handling and transporting animals and animal products increase the risk of zoonotic disease incidence and transmission.

“Working in forests for various reasons, including hunting, processing, and transporting wild animals and their products are among the activities that predispose humans to zoonotic disease risks. Markets selling the meat or by-products of wild animals are particularly high risk due to the substantial number of new or undocumented pathogens known to exist in some wild animal populations, including those that co-exist with livestock and other domesticated species.”

The researchers also highlight that changes in temperature, rainfall patterns and ecological conditions because of climate change affect the habitats of disease-carrying vectors such as mosquitoes and ticks, potentially expanding their range and increasing incidences of disease transmission.

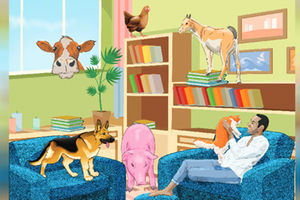

They point out that the most common animal species that are reservoirs for zoonotic diseases include non-human primates, bats, rodents, small carnivores, swine, rabbits, and dogs, so handling these animals needs great care.

“This does not mean, however, that they should be targeted for extirpation or removed from the ecosystem simply because they pose zoonotic disease risks. The balance of biodiversity is the most important consideration,” they note.

The researchers also found that challenges including increased rates of human population growth and mobility, urbanisation, food preferences, and handling of domestic animals, together with human behaviour and cultural have contributed to the decline of the delicate balance between humans and nature.

“Thus risks of zoonotic diseases transmission have been accentuated in some contexts.”

This is why they are of the view that addressing these challenges requires multi-sectoral collaboration and investment in healthcare infrastructure, veterinary services, and public health systems.

“The need for an integrated ‘One Health’ approach towards managing zoonotic disease transmission and emergence, to reduce risks of epidemics and pandemics and increase preparedness is more vital than ever.”

[email protected]