Why some women on contraceptives are getting pregnant

Caroline Gathura, a nurse, during the interview in Nyeri town on August 18. She conceived five months after having her coil inserted.

What you need to know:

- It remains a puzzle for the country, where six in every 10 women accessing modern contraceptives are recording unwanted pregnancies.

- Are the methods failing because they’re substandard? Are they expired, or are the women not just adhering to the usage instructions?

Kenya has made notable strides to improve the uptake of modern contraceptives, but what could be going wrong for women who are getting pregnant while using family planning methods?

It remains a puzzle for the country, where six in every 10 women accessing modern contraceptives are recording unwanted pregnancies. Are the methods failing because they’re substandard? Are they expired, or are the women not just adhering to the usage instructions?

An online survey conducted by Healthy Nation with the subject “contraceptive babies” posed the question “who has ever conceived while they are on contraceptives?

From the responses, many of the respondents were using pills at the time of their conception though some did not reveal the method they were using.

The survey revealed that a number of women added a new family member without plans, thanks to the failure of the contraceptive methods.

A pregnancy test

“You know, I had no plans to give birth when my baby was just turning two years. I was planning to have another baby when he was three but it happened,” says one of the women.

By the time Issa Mukami, another respondent, realised that she was pregnant with her first child five years ago, she had been on a combined birth control pill (which contains both oestrogen and progestin) for four years.

One day she woke up with tender breasts. She thought it was normal since she experiences the same when her periods are nearing. However, this was coupled with morning sickness. On testing, she was three months pregnant.

“My periods are irregular. This pregnancy came at the worst time. I had no job and my boyfriend was not supporting me. But I still carried my charming girl, now three years, to term,” she says

She continues: “Even though I do not remember skipping any of my pills, what I remember is that I was not so consistent with the timing. Maybe this could have contributed to it. But I am not regretting it.”

For one Peris Njenga, the news that she was pregnant despite using a birth control method was shocking and devastating. She slipped into depression.

She spent her days indoors, crying and could not perform her normal chores. And as days went by, taking a shower was too tasking and her appetite was gone.

Having sired three babies, she had thought it was time to focus on her career in business as she had spent the past few years at home bringing up the children.

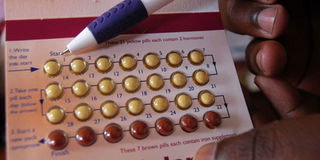

Contraceptive pills. Some 19 million women cannot access modern contraception

Missing her period for three days sounded a bell as she had always had a regular cycle. Upon taking a pregnancy test, the unexpected happened. “I was pregnant again,” she says.

“I was shocked and that marked the beginning of my stress for the first three months,” she says, adding that the fourth pregnancy’s journey was one of the most traumatising.

“I was bleeding throughout the journey to an extent that I was placed on bed rest. I feared I would lose my “unplanned baby”,” she says.

It took the intervention of her husband and friends to walk her through the acceptance journey. “It was not easy.”

At the time of conception, she was using Intra-Uterine Contraceptive Device (IUCD) or coil as her birth control method of choice.

However, subsequent ultrasounds revealed that the IUCD was still intact at the original position, which made it hard to understand how she got pregnant. She says she suspects there are fake coils being peddled in the market.

For years, she has used a number of family planning methods, both hormonal and non-hormonal, primarily to ensure the gap between her children is ‘reasonable, though she stuck with the non-hormonal — IUCD — since she could not keep up with the side effects of the hormonal contraceptives including gaining weight.

“All through I have used the IUCD to plan my family and that is how I have achieved a four-year gap between my three children,” she says.

It’s also possible that certain types of intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUD or coil) can cause you to have heavy periods. Photo/FILE

For two years now, Caroline Gathura, a nurse at a medical facility in Nyeri County, has not subscribed to any family planning method as she holds reservations about the hormonal type of contraceptives. She conceived five months after having her coil inserted. She was sure that she was safe and would only give birth at her best time.

The five months were smooth, with no pregnancy panic and no periods. She led her normal life of partying and binge drinking without knowing a foetus was developing in her belly.

Sudden mood changes, irritability and morning sickness that pointed to pregnancy symptoms, which were confirmed by multiple tests and an ultrasound, changed everything. Caroline was three months pregnant.

“I did two pregnancy tests just to be sure because I could not believe I was pregnant as I had signed up to the contraceptive method to enable plans for when I wanted babies. It was a mess as I wasn’t prepared to have babies,” she says.

The ultrasound showed that the IUCD had moved from the original placement, which she suspected could have led to the pregnancy.

“It took me a while to accept the pregnancy until I has a soulful conversation with my mother. Since then I have been afraid of using any family planning methods that are available,” she notes.

The five women are a representation of what many women in the country and even globally are experiencing — their stories are not unusual.

This is a replica of study findings done among married or cohabiting women aged 15–39 years in three rural sub-counties of Homa Bay County — Ndhiwa, Rachuonyo north and Rachuonyo South, which reported a 20 per cent failure of the methods they were using.

This means that out of 10 women who were using a birth control method in the three sub-counties, at least two reported a failure.

From the findings, out of the 896 women (18 per cent), a total of 166 women reported dissatisfaction with birth control methods, mentioning a failure of at least one method.

The study conducted by Dr Francis Obare and Wilson Liambila from the Population Council, United States, Reproductive Health Programme and Dr George Odwe from the University of Nairobi, was published in the Intechopen journal in 2017.

The study further indicates that close to half (43 per cent) of the women who reported contraceptive failure were from one sub-county (Ndhiwa). Similarly, half (50 per cent) of the women experiencing method failure were aged between 20 and 29 years.

The likelihood of experiencing method failure was significantly lower in Rachuonyo North and Rachuonyo South.

Forgot to take pills

Failure of injectable contraceptives and pills from the study was partly because of challenges with adherence to the methods. Some women reported that they forgot to return to the facilities for the methods on the dates of appointment while others forgot to take pills on certain occasions.

Others reported using strong antibiotics at the time they got pregnant, which they suspected might have interfered with the efficacy of the methods and thus exposed them to the risk of pregnancy.

“Women who got pregnant while on implants suspected that they were provided with expired commodities. Some reported that the implants might have disappeared in their bodies and thus became less effective.”

In 2020, Kenya attained a contraceptive prevalence of 61 per cent, surpassing the target of 58 per cent. Last year, according to performance Monitoring for Action Kenya data, the country was stuck at 61 per cent, which is still above the target.

Unwanted pregnancies result from non-use of contraception, use of ineffective methods, contraceptive discontinuation or switching for reasons other than wanting a pregnancy and contraceptive failure.

Last year, the government was on the spot for releasing expired and contaminated family planning implants to Kenyan women and it is only after the Nation published the findings that the consignment was recalled.

The recipients were advised to halt their usage, with further distribution suspended.

For a year, the products were at the Port of Mombasa because of clearance bottlenecks. The products had grown mould.

From the study, pills had the highest failure rate at 30 per cent followed by injectables (17 per cent), and withdrawal (15 per cent). In contrast, method failure was low for condoms and implants at four per cent each.

The findings indicate that contraceptive failure resulted from deficiencies either on the part of the user or the provider. In particular, the failure of injectables, pills and condoms was mainly due to challenges with adherence on the part of the users.

The finding suggests the need for expanding the range of contraceptive methods and providing adequate information, counselling for women and couples to enable them to make informed decisions regarding methods that are appropriate and easy for them to use.

The failure of more effective methods such as implants and IUDs was partly due to unskilled health workers offering services in some facilities .

“Provider deficiency could be due to lack of appropriate skills, workload or lack of relevant equipment. For instance, the methods require highly skilled personnel to administer that might be lacking in the rural community where the study was conducted,” it states.

The finding suggests the need for addressing health systems challenges that affect the provision of the more effective long-acting and permanent methods including staff availability, inadequate supplies, and lack of or faulty equipment for administering long-acting and permanent methods.

According to a report by the United Nations Population Fund dubbed “Seeing the Unseen: The case for action in the neglected crisis of unintended pregnancy, the World Population 2022”, nearly half of all pregnancies totalling 121 million being reported each year globally are unintended.

The report warns that this human rights crisis has profound consequences for societies, women and girls and global health.

It further states that over 60 per cent of unintended pregnancies end in abortion and an estimated 45 per cent of all abortions are unsafe, causing about five to 13 per cent of all maternal deaths, thereby having a major impact on the world’s ability to reach the Sustainable Development Goals.

“We know the steep costs associated with unintended pregnancy costs to an individual’s health, education and future, costs to whole health systems, workforces and societies. The question is: why has this not inspired more action to secure bodily autonomy for all?” Asks Dr Natalia Kanem, executive director United Nations Population Fund.

In Kenya, according to a study conducted by the African Population and Health Research Centre, about 40 per cent of pregnancies are unplanned; with 500,000 abortions carried out in the country in 2012, meaning that at least one abortion was procured in every 21 women capable of giving birth.

Abortion rate

The abortion rate for Kenya is estimated to be 55 per 1,000 women of reproductive age (15-49). This rate is very high when compared to other rates in Africa. It is on a par only with Uganda, which, in 2003, had a rate of 54 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age.

However, according to Dr John Ongéch, a senior leading gynaecologist and obstetrician in Nairobi, failure of most contraceptives more so the pills is attributed to non-adherence to the methods.

In regards to the pills and IUCD, Dr Ongech calls on women to comply and religiously take the pills to avoid failure rates. While the pills have a “perfect use” rate, the “typical use” rate is much lower.

“I have never seen or recorded a case of a failure of a pill if the woman was taking the pill every day and at a stipulated time. A higher percentage of pill failures is always non-adherence,” he says.

“Some of the women, after forgetting to pop the pills, rush to double the next day or take the drug at the wrong time.”

He cites non-adherence as a contributing factor to a majority of pregnancies that are reported at his clinic.

He also points out that low-quality products in the country could easily lead to failure of the methods.

On IUCDs, Dr Ongech tells Healthy Nation that a number of coils have failed for his clients, which he attributes to the failure of the clients to go back for a clinical check.

“A coil moves and once it is inserted, the woman is then advised to go for further check-ups after every three months to verify whether the coil is in still intact or it has moved, but they do not come,” he says.

Most of the women, he says, skip the clinical visits and complain later about the methods.

He further advises that with the coil, women should ensure that the insertion is done by qualified personnel to reduce the failure rates.

“This is one of the highly effective methods and it’s effective immediately it is placed. If it is placed by qualified personnel and follow-up is done to make sure it does not move, there’s no chance for user error.”

He observes that in most cases, for the IUD that lasts for five and 10 years, there is a three to five per cent chance it may be expelled by the body. Heavy bleeding can interfere with the placement of the coil and is a sign that the IUD has been expelled.

“If you are experiencing heavy bleeding, it is always advisable that if you are using the coil you go for check-up to find out whether it has been moved by the flow or it is still in place,” Dr Ongech says.

Another aspect, according to Dr Ongech, that can cause failure in some of the family planning methods is some antibiotics that he ruled out are not so commonly taken by women.

How this works, he explains, most methods contain oestrogen that helps prevent ovulation and subsequent conception from occurring but when one takes antibiotics when on family planning, they tend to decrease the level of oestrogen hormones in one’s blood and slow how the liver processes these hormones; hence the risk of one getting pregnant.

[email protected], [email protected]