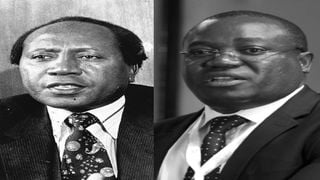

From left: JM Kariuki, Robert Ouko, Chris Msando, Julie Ward (top) and Carol Ngumbu.

| Nation Media GroupKenya@60

Premium

Missing bodies and the making of Kenya@60

As Kenya marks 60 years of Madaraka, self-rule, it is important to reflect on those we have failed to account for, the ones we lost; literally. How have their missing bodies been used by those who rule to frame ideas of the self, of what a Kenyan should be? How have missing bodies shaped the nation?

But how can an adult with no medical history of chronic forgetfulness disappear? When we use the phrase “I have lost so-and-so” it is a euphemism. We don’t really mean that we don’t know where the person is, we mean that they are no longer with us in the way that we have always known them to be.

We feel lost, at a loss, because death has turned someone we love into something we can only dispose of; what makes it whole is missing, forever lost. What happens then, when we don’t even have that something to dispose of? How do we grieve when there is no body? How do we determine the end when we cannot trace the steps that led to that moment of loss or find the final location of a life once lived?

Death is a confluence of changes. It transforms the individual’s physical body. It necessitates a shift in the ways that we, the living, relate to the person who is now a body. The body shifts social relations between us, the living, and when it is missing, that void can tear those relations irreparably.

But voids can also provide the impetus for repair. Indeed, some missing bodies have reconfigured the nation. They became the gospel by which we teach transformative politics, a politics through which the state must die for a nation to be born.

From left: JM Kariuki, Robert Ouko, Chris Msando, Julie Ward (top) and Carol Ngumbu.

The most iconic corpse in the making of the Kenyan nation is the mislocated corpse of Dedan Kimathi, the Mau Mau freedom fighter hanged by colonialists on February 18, 1957.

Kimathi’s corpse is mislocated in the sense that it was hidden from the public, the location of his grave buried in the annals of founding President Jomo Kenyatta’s state of amnesia.

State apathy in relocating Kimathi’s remains to a place of honour — whether that be his home or a national heroes’ corner — is an example of the state’s ability to use a missing body to control national becoming.

President William Ruto address mourners who had attended the burial of the late freedom fighter Mukami Kimathi in Njabini, Nyandarua County on May 13, 2023

In December 1968, President Kenyatta’s right-hand man, Mbiyu Koinange, revealed in Parliament that Kimathi’s grave at Kamiti Prison was fenced. So the location was known to the government then. Three years later Kamwithi Munyi, assistant minister in the Office of the President, gave this reason for scuttling the reburial plans Koinange had promised: “Singling out individuals in the manner implied … would be inconsistent with the spirit of building a united nation.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, whenever the question of (re)locating Kimathi’s remains came up in Parliament it was scuttled with increasingly stinging remarks about Mau Mau and dismissive attitudes to the idea of creating a national heroes’ cemetery.

But in 2003, Vice President Moody Awori promised that the Kibaki government would consult those who carried Kimathi’s remains “then we will exhume the bones and use the current methods of identification to confirm whether they are the right bones. Once we do that, we will accord our hero a decent burial”.

We heard this promise yet again last month when President William Ruto attended the burial of Kimathi’s widow, Mukami. Whether this renewed promise will amount to mourner hypocrisy or rise into a fine example of both the politics of repair and the work of cultural restitution remains to be seen. We have already seen the value of the politics of repair arise from a not-too-dissimilar instance of a mislocated body.

Stephen Mbaraka Karanja was arrested by police in Ngumo, Nairobi, on April 6, 1987, never to be seen again. On May 22, 1987, his wife, Naomi Waithera, filed a habeas corpus application in the High Court. In response, CID Director Noah arap Too swore an affidavit stating that Karanja was shot dead as he escaped, a death certificate was issued, and the body was buried at an Eldoret cemetery.

In a letter to Waithera’s lawyer, Obadiah T. Ngwiri, Too echoed the colonial logic of disposable populations when he wrote, “If you knew what type of character your client, is you would not be pestering me with these silly threats.” Ngwiri told the court that as a citizen of Kenya and regardless of his character, Karanja “was entitled to protection by the police and not elimination”.

Police dug up 18 graves on June 25, 1987, but failed to find the body of Kiambu farmer Stephen Mbaraka Karanja who was shot dead and buried secretly by CID officers . The search for Karanja took place at the Eldoret municipal cemetery.

Justice Derek Schofield interpreted the Latin writ of habeas corpus literally to mean, “show me the body”, and ordered that Karanja’s corpse be exhumed and taken to City Mortuary for a post-mortem. Police dug up a total of 27 graves and couldn’t find a body with a bullet hole in the skull. Justice Schofield threatened to cite Too for contempt of court. Chief Justice Cecil Miller promptly transferred the case to Justice Akilano Akiwumi. Justice Schofield resigned. On April 29, 1988, Justice Akiwumi reversed Schofield’s order ruling that the writ of habeas corpus only applies to living persons.

This year-long case played out in the heyday of Mwakenya and allied acts of defiance against the Moi government, so in the court of public opinion, Karanja’s missing body was invariably linked to politics; to the harrowing fate of suspected dissidents. Twenty-three years later, the rights of arrested persons were revised in a new constitution.

Article 49 (10 (f) of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 provides that an arrested person “be brought to a court as soon as reasonably possible but not later than twenty-four hours after being arrested”. Stephen Baraka Karanja’s missing body reframed that fundamental principle in our criminal justice system, a principle that amplifies the Hobbesian view that morality is not the mission of the state in the sense that every citizen deserves government protection.

In the logic of ‘the Father of the Nation’ rhetoric that dominated independent Kenya’s early years, the state didn’t want a canopy of heroes, it needed docile subjects. Consider the case of Kung’u Karumba, another Mau Mau freedom fighter. After independence, he established himself as a businessman, running an abattoir at Dagoretti market, a textile factory and transport company. Karumba was last seen in Jinja, Uganda, on Saturday, June 15, 1974.

The search for Karumba escalated quickly. It began with a press conference at which Sammy Maina, the organising secretary of the Kanu party Nairobi branch broke the news of Karumba’s disappearance.

A report in the Evening News of June 19, 1974, was immediately taken up by Nakuru Town MP Mark Mwithaga, midway through the budget debate in Parliament. The story grabbed every newspaper headline as the Kenyan Government asked Uganda, under strongman Idi Amin, to “verify Karumba’s whereabouts”.

The most curious report, however, was an editorial in the Daily Nation of June 22, 1974, titled, “The Karumba Mystery”. “A citizen, no matter how humble he is, is an epitome of the State … In this editorial we give compliments and praise to our Head of State, the President Mr Jomo Kenyatta and his government for showing much concern about a simple, humble citizen.”

The editorial laid emphasis on the fact that though Karumba had been a freedom fighter, he was “unassuming, humble … had not sought political office nor has he sought to indulge in internal intrigue … no one who claims to have political patriotism can point a finger at him or a blemish at his thinking or political activities…”.

Was this editorial suggesting that those with political ambitions that challenge the status quo are the kind of people who deserved to disappear? This is such a colonial idea of disposable people. Post-independence governments have perfected this thinking.

Eliminating those who irritate the system also has the effect of cowering the rest into conformity. Indeed, a core ingredient in the making of the Kenyan nation is state-driven fear and curated silence. And, as the novelist Tariq Hoosen reminds us, “There are many kinds of death and the worst one is the one suffered while living in silence.”

The gun carriage carrying Mzee Jomo Kenyatta's flag-draped coffin is drawn through the streets of Nairobi for the funeral on August 31, 1978.

The Jomo and Moi years were so heavily laden with fear that it took 26 years before anyone publicly stepped up to explain Karumba’s disappearance. Ibrahim Mungai, who had hosted Karumba in his Bugembe home that fateful weekend in June 1974, revealed to journalist Kamau Ngotho that Karumba was killed at Mabira Forest over a debt he had gone to collect from “a woman called Margaret, who was the mistress of a senior Ugandan military officer”.

Mungai said Karumba’s body was most likely tied “to a heavy stone and throw[n] into River Nile or Lake Victoria where it would either be eaten by crocodiles or would sink far down, never to be found”.

The late Freedom Fighter Dedan Kimathi. Parliament was told that his grave was "fenced and looked after" in Kamiti and that "plans were afoot to see how a better grave could be prepared.

Twenty months after Karumba vanished, another Kenyan went missing in Uganda. Esther Chesire was last seen at Entebbe Airport on Friday, February 13, 1976. Esther had been in the company Sally Githere, a fellow student at Makerere University, when Ugandan police took her aside for questioning.

Vice-President Daniel Moi, who was also the MP for Baringo Central, where Esther’s parents lived, joined the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Dr Njoroge Mungai, in ceaselessly demanding answers on Esther’s whereabouts from President Idi Amin. Uganda denied responsibility and told Kenya to “mind its own business”.

President Daniel Toroitich arap Moi, 59, is nominated as the sole candidate for the presidency, August 24, 1983.

The University of Nairobi students urged the Kenyan Government to suspend the 30-year-old exchange programme of the defunct University of East Africa through which students were distributed amongst Makerere, Royal Technical College, Nairobi, and Dar-es-salaam College. The government promptly bused its students from Kampala to Nairobi. Gone were the days of easily finding a spouse in the neighbouring country.

In 1974, it had taken five days for Karumba’s disappearance to reach the press; it took a month for Esther’s to make the news. Makuyu MP, Jesse Gachago, told Parliament on April 6, 1976, that “it had now become routine for Kenyan nationals to disappear in Uganda and this was causing a lot of anxiety.” Now, to be a Kenyan was to be a person who viewed foreign nationals with suspicion.

Ex Ugandan Dictator Idi Amin Dada. He died in 2003 while in exile

There is an inescapable element of class considerations in the way the missing bodies of Karumba and Chesire triggered a reconfiguration of Kenya’s external policy regarding Uganda, and its policy on higher education. Families with access to power — mainstream media; Parliament; the President’s ear or inner court — galvanise a government in their loss. Our history of disasters provides another chapter of nationally felt losses and government (in)action in the painful theatre of missing bodies.

On January 30, 2000, the ill-fated Kenya Airways flight KQ 431 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean just off the coast of Abidjan moments after take-off. Of the 169 people who died, 22 were Kenyans. Twenty-three bodies, including that of John Mugo, KQ’s regional manager for West Africa, have never been recovered.

The recovery of bodies went on for three weeks. The Moi government sent Kenya Navy divers to help; one of them drowned in the process. The Kenya Airways leadership skipped a memorial service held at KICC, even though they had set up a crisis centre at Hotel Intercontinental staffed by psychiatrists and counsellors to support families of the victims.

Novelist Paul wa Munga observed that the traumatised families of those who died daily in horrific road crashes, such as the one in which a Kenya Bus had rammed into a trailer on the Nakuru-Nairobi highway the previous week, were not given similar support by government agencies. A few days later, President Moi promised that a crisis centre would be established “to handle the contingencies of any tragedy that befalls Kenyans.”

The centre was never established. From road crashes, tanker explosions, ferry disasters, floods, two other air crashes, and several terror attacks, our governments manage disasters on ad hoc basis – relying on the magnanimity of the Red Cross, international agencies, foreign governments, and the remarkable ingenuity and compassion of ordinary Kenyans.

Missing Bodies: Every contact leaves a trace

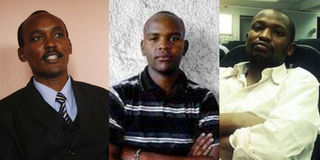

One of the principles of forensic science holds that every contact leaves a trace. So why, in this era of digital surveillance and big data, are we unable to trace Kelvin Macharia, Bogonko Bosire, Albert Muriuki, Mwenda Mbijiwe? Despite cell phones, car-trackers, traffic cameras, drones, and voluble media campaigns to publicise their unknown whereabouts, there is silence.

From left: Security analyst Mwenda, IEBC clerk Kelvin Macharia who disappeared during the 2013 General Election, and Bogonko Bosire who went missing in September 2013.

Add to these four recent examples of missing persons the hundreds of enforced disappearances documented every year by civil society groups in the Missing Voices Report. Where are all these Kenyans, what happened to their bodies? What does their collective erasure rob the country of? How might we have grown into a humane society, a robust economy, a just democracy if they were still here with us?

Beside the missing, we must think of those who wait for the reappearance of their loved ones, or the discovery of remains that will confirm a death. The waiting wears them down. Haunted, emotionally fragile, anxious, swinging between hope and despair, broken, they sink into ghosts of their former selves. A nation of haunted persons is not a happy place. And neither is it a democracy of robust productivity.

Our laws state that one is presumed dead if they, or their body, have not been traced for seven years. Rituals for the presumption of death include publishing a notice to that effect and applying to the High Court of Kenya for issuance of writs to confirm this presumption. What if there is no family, or none that is able, to undertake these rituals?

When these rituals do not take place, the government’s ultimate task on a body — issuing a death certificate — cannot be performed. So, we have no person and no record of their exit. How do incomplete government registers impact the everyday lives of those left behind? How do they impact government planning and policy?

The journalist and ferryman Sudirman Adi Makmur who travels with the dead across borders as part of the funeral services required by many reminds us that, “the body is a threat; it can testify – the skin, the hair, the blood, all tell a story.” We have seen the truth of this in the many instances in our history when bodies have refused to disappear.

For instance, JM Kariuki, Robert Ouko, Julie Ward, Agnes Wanjiru, Mark Yebei, Chris Msando, Carol Ngumbu, Willie Kimani, Joseph Muiruri, Tobias Cohen, #RiverYalaBodies, and most recently, the Shakahola cult victims. These bodies have come to light somehow floating above the surface of the water; peeping from a thicket for a herdsboy to stumble upon; uncovered by the whispers from a disgruntled accomplice to a crime.

Julie Ward, who was found murdered in the Maasai Mara Game Reserve in September 1988.

In the thousands of micro-narratives of everyday existence that make up Kenya, there are so many harrowing tales of bodies that never resurfaced. Not all of them are linked to our national politics of attrition. Let me tell you of two of them.

Missing Dutch billionaire Tob Cohen. His body was found in a septic tank in his compound in Kitisuru, Nairobi, on September 13, 2019. PHOTO | JOEL ODIDI | NATION MEDIA GROUP

Eldoret, Monday, June 10, 1996. Gachanja Owiti, 34, dropped Irene, his wife of five years, at her place of work as they discussed what to do about the nanny they had just left with their eight-month-old son. They agreed to finish that conversation in the evening as Gachanja drove off to drop their four-year-old daughter at her nursery school. Irene has not seen Gachanja since.

He was a banker at Savings and Loan, and until 11am that day, when two plain-clothes policemen burst into her workplace looking for him, Irene was certain Gachanja was busy at work. She dashed to the bank, where a manager explained to her that her husband was suspected of stealing Sh2 million.

She didn’t believe it. Nothing in her husband’s life revealed that he was awash with cash. A week earlier, Gachanja had gone to Mombasa to collect a car he had imported from the UK. He had told Irene that he took a loan to buy it. It was the same car in which he dropped her at work that Monday morning.

Dazed, Irene went in search of Gachanja’s best friend. He didn’t know where Gachanja was. Even when police held the friend in the cells the following weekend, interrogating him about Gachanja’s whereabouts, the friend had no answers to the puzzle. The police stormed Gachanja’s home in Eldoret and confiscated Irene’s bank cards and those of her children’s savings accounts.

Gachanja’s car was found at the home of a female friend in Kilimani, Nairobi. In it were the car keys, Gachanja’s ID and his wallet, which contained the Sh2,000 Irene had given him that Monday morning to pay their milk supplier in Eldoret. Gachanja had dropped off his car while his female friend was out at work. He showed up briefly at the Sacco offices where Irene’s sister worked. She waved at him as she finished with a customer. When she looked up again, he was gone.

Weeks later, a former classmate of Gachanja’s at Jamhuri High School travelled to Eldoret with news. This bosom buddy worked for an oil company in Mombasa, and he is the one who had travelled to the UK to select two cars his and Gachanja’s. Gachanja had promptly wired his share of the purchase price from Savings and Loan.

Now, this man and his wife were in Irene’s house telling her that a few days after he went missing in Eldoret, Gachanja had shown up on their doorstep in Mombasa at 3am, dripping wet. His first words were, “I have just come from the Indian Ocean. I realised suicide is not as easy as I thought.”

They had talked through Gachanja’s troubles, his friend sketching a plan to find Gachanja a lawyer to handle the police inquiries. Gachanja did not wait to see the plan through. By the time the couple returned from work, he had left, their househelp unaware of his next destination.

As far as Irene knows, no formal search for her husband was ever mounted. She was too afraid to look in mortuaries or to seek help from the police. Her in-laws told her that the car was repossessed by the bank. The police eventually returned Irene’s documents. No presumption of death was made; no death certificate was ever sought or issued.

Irene oscillated between fear and hope, thankful for the support of her family in maintaining a now fragile relationship with her in-laws. Many years later, she saw a relative’s death and funeral announcement in the newspapers. Her eyes settled on the words, “Uncle to the late Gachanja Owiti.” And with that, she abandoned the hope that her husband would return.

My second example is the story of a search that led to a painful dead-end, literally. Tom Ochola was a poet and a lecturer in the Literature Department at Maseno University College. In October 1993 he travelled from Maseno to Nairobi to attend the Memorial Cultural Festival of the Kenya Oral Literature Association (Kola) in honour of Dr Jane Nandwa and Henry Owuor Anyumba at the University of Nairobi.

According to his wife, Lena Kiprop, Tom, who had recently been diagnosed with diabetes, had been referred by the clinic in Maseno to a doctor in Nairobi to review his infected leg. A few months earlier, his other leg had been amputated at the knee on account of gangrene.

Tom’s colleague, Prof Peter Amuka, remembers Tom as being morose during the tea-break at that Kola memorial of October 7, 1993. In fact, they continued a rather dark conversation they had started at Maseno a few days earlier, a chat about drunkards who get hit by runaway motorists and how their bodies lie in morgues unclaimed. At Maseno, Tom had told Amuka rather ominously that if the doctor in Nairobi recommended another amputation, “Ok u bi nena kendo — Nobody will see me again.”

Days after the memorial festival, Tom’s estranged wife, Lena, then a lecturer in educational psychology at Maseno, went in search of him. Surprised to learn that he had not returned from Nairobi, she alerted their friends and bosses who immediately embarked on a search for Tom in the capital city. Lena was nursing their three-month-old son so she couldn’t join the search party in Nairobi.

Entrance to Maseno University's main campus.

As word of Tom’s disappearance spread through Maseno campus, angry students turned on Lena, blaming her for Tom’s fate. Prof B A Ogot whisked her away from the violent crowd. The college principal, Professor William Ochieng, gave Lena compassionate leave.

Meanwhile, her own family was unsupportive, pointing to her choice of an inter-ethnic marriage as the source of her woes. Fear, suspicion, anxiety, and isolation marked Lena’s life from this point. One of her colleagues at Maseno remained firmly by Lena’s side even as the news from the search party in Nairobi pointed to the worst.

At City Mortuary, attendants eventually traced Tom’s documents – his ID and the referral letter from Maseno clinic to Aga Khan Hospital. They explained that Tom had been found unconscious on a Nairobi street at 3am by a man called Mwangi who took him to Kenyatta National Hospital.

The entrance to the City Mortuary in Nairobi.

When Tom died, his body was transferred to the City Mortuary and now, weeks after he had been booked there, attendants said his unclaimed body was buried in a mass grave and it was impossible to trace the actual site. The documents on Tom’s body gave every indication of his employer. So why didn’t the City Mortuary make any attempt to contact the university and through it, his relatives?

Tom’s mother found a way to appease the horror of her child being buried by strangers, with strangers, in a mass grave. Luo rites provided the remedy. As I listen to his widow Lena explain how Tom’s mother and his paternal relatives in Uyoma organised a symbolic burial in which they interred a banana trunk to represent the missing body, the words of Jonathan Kariara’s epic poem flood my mind:

“If you should take my child, Lord

Give my hands strength to dig his grave

Cover him with earth

Lord, send a little rain

For grass will grow.”

Tom’s remains may have been lying in an unmarked grave somewhere in Nairobi but through this banana-burying rite, his spirit was released to commune with his ancestors.

Tom Ochola’s fate at City Mortuary shows us that on the other end of our tragic theatre of missing bodies lies another sad absurdity known as unclaimed bodies. The Public Health (Public Mortuaries) Rules, 1991, made under the Public Health Act Cap. 242 say an unclaimed body should be removed from the mortuary within 10 days or else it is buried in a mass grave after the officers issue a 21-day notice and obtain the court’s permission for disposal.

On January 27, 2023, Nairobi City County Health Services published such a notice in the Daily Nation stating that there were 292 bodies lying at three county public mortuaries – Mama Lucy Kibaki Hospital, Mbagathi County Hospital and City Mortuary. Two months earlier, Kenyatta National Hospital had disposed of 233 unclaimed bodies, many of them infants and children who had either been abandoned at the referral hospital when they were ill or left uncollected when they died. The numbers are staggering. Between 2003 and 2006, Nairobi’s City Mortuary disposed of 2,500 unclaimed bodies.

According to the Nairobi County notice of January 2023, the identities of some unclaimed bodies were established through the government’s fingerprint database. In some instances, the next of kin are untraced perhaps a man left his village to find work in the city, lost touch with his loved ones, died, unknown wherever he lived, unmourned as he lies at the morgue. Other times, as with street families, people have no legal right to claim the body of someone they knew, perhaps loved, and maybe even lived with. Their ties on the street are, sadly, disregarded as legally inconsequential.

In other instances, the next of kin are aware of the death, they are known to the mortuary officials, but they simply cannot afford to take away their dead. A temporary grave at Lang’ata Cemetery costs Sh7,000 for an adult, Sh4,000 for children and Sh2,000 for infants. The cremation of an adult costs Sh16,000 and that of a child Sh15,500.

How we deal with death announces who we are and what we believe. A society that cannot devise a civil system to assist citizens in the lower economic cluster to attend to their dead by way of releasing them in dignity to reconnect with nature and with their ancestors, is really saying that connections and bonds in certain classes are worthless and must be broken. Inequality amongst the living is extended to the dead. As if we do not collectively bear responsibility for the deaths of other people.

But Kenya is a place of cruel extremes, so sometimes what we have is the opposite of this problem one body is claimed by many parties. Whichever party is eventually awarded the body for burial, as we saw in the outcomes of the respective court cases filed by Prisca Buluku in September 1978; Wambui Otieno in December 1986, and the widows and brothers of former Provincial Commissioner John Mburu in October 1981, someone eventually goes home without a body. Their loved one is missing from the place they believe was designated to be the rightful final resting place.

Was Jomo Kenyatta buried in the right place? Beyond inscribing him as different, made apart from the citizenry, what other political work is done by the presence of his remains on prime land in Nairobi’s city centre, inaccessible to the Kenyan public but paid for by their taxes, reserved as a shrine where visiting heads of state lay wreaths?

When Heroes Corner at Uhuru Gardens finally finds willing takers, will Jomo’s remains be moved there along with those of the Kapenguria Six (minus Kung’u Karumba)? This is what the 8th Parliament that established the special burial ground proposed. But what does Kenyatta’s family want? Do they feel a disconnection and consider his spirit missing from the Gatundu home he loved so deeply?

Between our vile politics and a depressing economy, the Kenyan state manufactures missing bodies and mismanages many unclaimed ones. These (in)actions have produced a nation governed by bursts of fury, unending fears, deep silences, and terrible apathy. News of the missing enter our timelines on social media, and our shock, outrage, and sometimes even our dark humour and callousness, pour out in a deluge. For a day or two. maybe even for a week or three before the next news cycle of shocking rapes, road accidents, heinous murders, brazen corruption and so on, fills the news. We are distracted. We forget.

However, to borrow a phrase from the American novelist Jesmyn Ward, “[Our] ghosts were once people and [we] can’t forget that.” We must never forget that. In the lives that they led, and in the disappearances and erasure that they suffered, they too contributed to the making of Kenya@60. For when we consistently lose people without trace, we lose more than just the people themselves. We lose our soul. Kenya@60 is a country in need of a soul.

How do we humanise this nation of broken promises, cruel elimination, forced abandonment, and callous neglect? The idiom “We have lost-so-and-so” places a burden on us — as if we were careless or late to keep an appointment. We must bear this burden fully and be less careless about literally losing people. Can we repair the instances when mislocation of loved ones has occurred?

Maybe one day we will establish a Missing Persons Bureau one that will be staffed with sociologists, perhaps an archaeologist, and some pathologists. If we ever do so, may this bureau have the resources, the resolve, and the grace to find and give dignity to the ones we lost.

Dr Nyairo is a fellow at the Wissenshaftskolleg zu Berlin (Institute for Advanced Study).

This article is taken from her ongoing study, “Enacting Community: Death and Funerary Practice in Modern Kenya” – [email protected]