The mass protests against the Ruto regime are an expression of Kenyans’ frustration and dissatisfaction with the performance of their government.

The first time Rael Chepkohkogh, a 57-year-old resident of Bendera in Kapenguria, West Pokot County, heard the term, Gen Z, she had no idea what it meant.

It was in June this year when the youth uprising over the Finance Bill, 2024 in Kenya made headlines.But now, she occasionally uses the word, right way or wrongly, but it has become part of her vocabulary.

“We hear that Gen Zs are children who reached Form Four and university and who were not wrapped in rags [due to poverty] but wore diapers,” she tells Lifestyle.

From the protests, she also heard of the term Finance Bill, which she says means “looking and adding money.”

“Before the Gen Z protest, we were unaware of the Finance Bill. We now know that it can make commodity prices rise. Since then, I’ve wondered, where will the government get the money if it makes us all poor?,” she says.

The youth uprising-related terms have permeated everyday speech, even among uneducated populations, in markets, yielding dictionary updates and slangified phrases.

Lifestyle asked James Akazile, 69, also a resident of Kapenguria, what he thinks Gen Z means. His answer was brave.

“Gen Zs are youth who are distractors and destroyers. They usually loot people’s property. They also don’t like the President. We elected the President, and they are the people who are against him. We don’t understand them,” he says.

“Why are they pushing elders to the wall? Where do they want the President to go to? Gen Zs have brought problems. These are children who cannot even afford to buy clothes for themselves and can’t build their own houses,” he says.

Asked if he knows what the Finance Bill means, Mr Akazile nods.

“What is this “painance, painance”,” he says.

James Akazile, a resident of Simotwo area in West Pokot county on July 17 ,2024.

Roselyn Ashiron, known among her agemates as “Mama Shogoli, is 37 years old. The chicken seller from Makutano town says confidently that she heard the term Gen Z when Haiti overthrew the government.

“What we saw in Haiti was very bad. Life in Haiti is bad. There are no people in Haiti. We don’t want to be like Haiti,” she says, adding, “I hear the Gen Z created chaos in the country, treating the President like a child. The President is our grandfather, and they should respect him,” she says.

On the meaning of the Finance Bill, Ms Ashiron says all she knows is that it is “something brought about by the President.” That it has something to do with IDs (identity cards) and KRA (the Kenya Revenue Authority).

“Finance Bill is a term used simultaneously with the term Constitution. We voted between bananas and oranges, and oranges won,” she says.

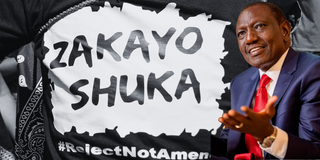

In Murang’a, locals have learnt new vocabulary and dance skills this year too. In the past, words like Zakayo (Zacchaeus was a tax collector mentioned in the Bible) were only heard in church and during CRE lessons in school, for it is rare to come across someone with that name.

Village folks have been taught by the Gen Zs that it can also apply to someone in leadership who loves taxes and more taxes. Margaret Njambi, 70, from Murang’a County, famously known as “Shosh wa Ruto” told Lifestyle that courtesy of the Gen Z wave, she now knows music tracks like Gotha Tena and Anguka Nayo, derived from the new-age sheng language spoken by younger generations.

Margaret Njambi Mwangi recalls her ordeal in prison during an interview at her home at Gikandu village in Murang'a County on August 6, 2024.

“As I laboured hard to understand why these children were protesting, I came to know about ‘Ngotha tena’. I think it means hit it again, while ‘Anguka Nayo’ mostly means that we pursue at whatever cost what we aspire for,” she tells Lifestyle.

Sasida Njeri, 75, says she had all along known that Katiba is the one that rules the country “but these children made me aware that Katiba in English is the Constitution since in their media interviews they would keep on mentioning it. She adds that her basic education many years ago did not teach her about words like sovereign power which, according to her, have become monotonous in the debates that surrounded the protests.

“As I listened to them on TV, I felt I had attained quality, modern education since I learnt other new words such as integrity, recall, impeachment, vetting... They kept saying these words and I came to learn they meant sacking elected leaders who have failed to deliver. Most importantly, I have come to know that there are generations that care less about the clans that I have known all along,” she said.

Ms Njeri adds that her grandchild, Virginia Wanja, is the one who taught her about the different generations.

Gladys Njoroge, who is the youth chairperson of the National Democratic Congress says “if there was good governance’s civic education that has been unleashed deep in the grassroots targeting those who did not get the privilege of “elitist education”, then it came packaged in these Gen Zs’ protests.

“It excites my heart to hear the village folks also saying such and such leader needs to be given “salamu” (greetings), which is Gen Z’s version of saying a bad leader needs to be pressurised by physical visits to be reminded of the covenant he or she has with the people who elected them into office,” she says.

Raymond Obonyo, 67, has spent most of his life in Homa Bay County. He was born and raised in Kanyada. He dropped out of school in 1971 when he was 14 years old. He is among those who have been playing catch up with Gen Z’s language. Mr Obonyo works as a security guard at one of the government offices. He likes listening to vernacular FM radio stations.

“They use a language that I can easily understand, Dholuo. I struggle with English and Kiswahili proficiency,” he says.

We ask him if he knows the meaning of Gen Z, and he answers: “‘Jen si’. I know the group. It is made up of young men and women.”

Mr Obonyo said that he first learnt of the word during the anti-government protests, but why the Gen Zs were protesting was not clear.

“I just know that finance is associated with money. That is why we have the minister for finance who determines how money is spent by the government,” Mr Obonyo says. “I also don’t understand why the President would be referred to as Zakayo and why he is being told to ‘shuka’ (climb down).”

An anti-riot police officer prepares to fire a teargas canister along Tom Mboya Street on July 16, 2024 during the anti-government protests.

Code-switching

Language, just like fashion, can be ephemeral, meaning new words regularly drive out old ones, segregating the older generations. This year, Gen Z has been inventing new words, which people above 40 years would struggle to understand. Code-switching among Gen Zs has also become commonplace.

Rose Ogoma, 43, who lives in Homa Bay says she has tried to learn sheng from her children, but it evolves too fast for her to catch up. Slang words like Gotha Tena are popular among Kenyan youth, Ms Ogoma says she has heard of them but does not know how and when to use them.

“I only hear such words on the streets but cannot use them because I do not know what they mean,” she says. “At least I know ‘salamu’, which is used by Gen Zs. This means confronting someone who has done you wrong, either online or physically.”