Premium

Children’s book revolution: How East African women took on colonialism after independence

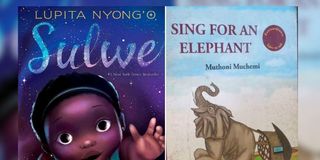

Children's books.

As independence from British colonial rule swept across East Africa in the early 1960s and freedom was won in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, parents and teachers worried about what their children were reading.

Most children’s books on the market were dominated by European writers like Enid Blyton. One of Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiongo’s most stringent criticisms of colonialism was the explosive effect of this “cultural bomb” in the classroom, as missionaries taught African students western cultures and foreign histories. This, according to Kenyan publisher Henry Chakava, was producing

"a new breed of black Europeans, who began to despise their own skin and background."

Publishers and African writers were quick to realise the gap in the market for literature that was suitable for a new generation growing up in independence. From the mid-1960s onwards, publishing houses began a concerted effort to produce such literature. What’s particularly noteworthy is that most of these authors of children’s books in this period were women.

As an historian of East Africa, these women writers and their children’s books formed part of my doctoral research. Not only have they been largely ignored by history, but their voices matter because through them we receive a unique insight into this period of East African history.

The women writers of independence

In the 1960s, ideas of decolonisation and Afrocentrism dominated East African culture and academia. The 1962 African Writers Conference was convened at Uganda’s Makerere College (today Makerere University). The University of Nairobi’s English Department was dissolved in a 1968 revolution led by East African writers and thinkers. It was replaced by a department of literature, and a department of linguistics and African languages. But such discourse happened mainly inside elite intellectual spaces and small circles.

We mainly know of male voices in East African literature from this period – the likes of Ngũgĩ, Okot p'Bitek and Taban lo Liyong. As men, they had more educational and professional opportunities, and better access to publishing networks. Women writers were seldom published and often dismissed or even ridiculed.

They found a gap in children’s literature. Women writers took it upon themselves to educate children about independence and the meaning of decolonisation. They did this outside of the academy’s ivory tower, with popular work that trickled down to all levels of society.

These authors included Barbara Kimenye, Asenath Bole Odaga, Miriam Khamadi Were, Pamela Kola, Anne Matindi, Elvania Namukwaya Zirimu and Marjorie Macgoye.

They wrote for children of all ages, creating fiction, folk tales, and works used in school textbooks. With their words, the women imparted lessons they believed were important for the post-independence generation to learn in order to undo colonialism’s “cultural bomb”. These were works of transformative potential that foregrounded African settings and lessons.

The Moses series

Some of the best known African children’s books of the 1960s and 1970s included the Moses series by Ugandan author Barbara Kimenye, one of East Africa’s most celebrated children’s book writers. The series follows the adventures and misdemeanours of Moses and his friends at the fictional Ugandan boarding school, Mukibi’s Educational Institute for the Sons of African Gentlemen. The Moses series was published between 1968 and 1987 by Oxford University Press.

Moses in Trouble, the fifth in the series, centres on an upheaval at Mukibi’s due to poor school meals. Moses and his friend King Kong “sneak off to the village duka (shop) to buy a packet of biscuits” and are later forced to go to nearby farms to steal food. Eventually, Moses is hospitalised with malnutrition.

Despite the seriousness of the topic, the narrative is humorous, and the Moses series remained popular for decades. The book contains subtle criticism of post-colonial political oppression. Mukibi’s can be seen as a replication of the (post) colonial state: it restricts the boys’ movements and demands complete obedience to authority, but fails to provide basic necessities.

With Moses in Trouble, Kimenye encourages even young readers to remain critical of authority, especially in a time when then-president Milton Obote’s rule in Uganda was becoming increasingly authoritarian.

Folk tales

African folk tales were another popular literary genre for children. African publishers encouraged that these be written and distributed across East Africa. One example is the collection East African Why Stories by Kenyan author Kola. It was published by East African Publishing House in 1966.

The stories recount the origins of the habits and characteristics of animals native to Kenya, with titles such as Why the Hippo Has No Hair or Why Baby Chickens Follow Their Mothers. As an educator, Kola understood the need for African stories to be read by African children. She wrote down the stories as they were told to her by her grandmother in the local Luo language before translating them into English.

The oral origins of the stories are reflected in the entertaining, conversational style in which they are written. Reading traditional folk stories was a way for African children to remain in touch with their heritage, which the colonial education system effectively eradicated.

Why this matters

The works of male authors continue to be celebrated today for their contributions to the East African literary canon. Fewer remember the role children’s book authors played in the Africanisation of written literature in the 1960s and 1970s – probably because most of them were women.

Looking beyond the texts discussed here, the women critiqued colonialism and neocolonialism, inequality, oppression, patriarchy and state authoritarianism, often representing marginalised communities.

In writing for young readers, these writers imparted their hopes for independence to them. Their texts reached all echelons of society, exposing children to ideas that allowed them to understand their changing world while serving as an antidote to Eurocentric education.