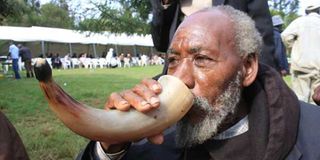

A man drinks mũratina during a traditional ceremony.

What was once a brew shrouded in secrecy and tradition is now finding a permanent spot in Kenyan social gatherings. Mũratina, the Agikuyu traditional alcoholic beverage, has broken free from its roots as a ceremonial liquor for elders to become the life of the party for younger, urban drinkers.

Gone are the days when mũratina was reserved for elders seated under trees, discussing weighty matters such as hunting. Today, it graces the tables of weddings, graduations, and even casual hangouts on weekends. And some of the drinkers are not even from the Agikuyu community.

“What we now have is a craze that knows no gender, tradition, age set or fear of the law. It is a craze where every other gathering is a reason to drink mũratina,” says Gladys Njoroge, the National Congress youth leader.

“We used to hear that before sipping mũratina, one had to pour libation in reverence to the gods...but nowadays we are toasting to every other kind of health...there are no traditions attached, we are just making merry.”

She attributes the growing thirst to its affordability. But well-to-do drinkers in Nairobi say mũratina’s allure lies in its inability to cause hangovers.

The take-up is partly being fuelled by social media. Content creators like Mbote Njogu have capitalised on its popularity, packaging himself as a self-styled ambassador of the brew, and showcasing it in videos and social media reels. In the social media posts, he is either mentioning the brew, carrying a jerrycan, or drinking it from a horn.

According to Agikuyu cultural researcher Kigo Kiranga, 81, mũratina was traditionally brewed for special occasions such as cleansing rituals, weddings, and community celebrations. It was never intended to induce drunkenness but rather to bring people together.

“Today, it’s being abused. Both the young and the old are drinking it to the point of finding themselves in ditches,” he says.

The brew draws its name from the Kigelia Africana (Sausage Tree), which produces fruits known as mīratina in Kikuyu.

The mīratina fruits, once harvested and dried, are immersed in sugared water and subjected to moderate heat to ferment for about five days.

For maximum effect, sugarcane juice and honeycombs are added, inducing the fun of spitting out dead bees while swallowing bee maggots, giving the mũratina drink its thrill.

Mũratina was traditionally brewed in large gourds (ndua) and served in medium-sized gourds (nyanja). Men drank from horns (rũhia rwa njohi), while women used special gourd cups (ndahi ya rũngũ). Before the first sip, a portion of the drink was poured on the ground to honour ancestors, and a drop was spat onto the chest and hands to bless one’s labour. Words of blessing would also be uttered, depending on the occasion.

Kikuyu Council of Elders Chairman, Wachira Kiago, laments that mũratina has strayed from its cultural roots, including the recommended drinking age.

“This was a brew prepared with care, for specific occasions, under the supervision of elders. Today, it’s being commercialised, abused by young people, and brewers are using chemical shortcuts.”

Mr Kiago argues that younger generations have embraced mũratina without understanding its cultural significance.

“Previously, only those over 40 were allowed to drink mũratina, and even then, in moderation. Now, it’s become a free-for-all, losing its original purpose,” he says.

“On special occasions, the young would be allowed sips shared in a cow's horn just to bond...otherwise drinking of mũratina was a preserve for elderly men and women.”

Brewing permits

With stricter liquor laws, traditional brewing practices also face challenges. Permits are required for brewing, yet many village brewers avoid the process. This has led to clandestine operations, where shortcuts—like adding molasses and artificial chemicals—replace the authentic fermentation process.

“What we now insist on as administrators is that our security teams remain vigilant to ensure this brew is not abused and does not find itself among the categories of killer brews owing to adulteration,” says Joshua Okello, the Maragua Assistant County Commissioner.

Margaret Njambi, 69, from Gikandu village in Murang’a County, says another tragedy facing mũratina is the near extinction of the mīratina fruit.

“The problem is that demand far exceeds supply,” says Ms Njambi, a seasoned brewer.

“The trees that provide mīratina fruits are disappearing, and brewers are turning to cheaper, less traditional methods.”

Ms Njambi recounts her struggles, including jail time for brewing without a licence.

But now, the demand is growing, especially towards the end of the year, as Kenyans order mũratina for wedding and burial ceremonies, circumcisions, newborn celebrations, goat eating feasts, graduation ceremonies, and even house parties.

“I know several brewers who received Christmas and New Year orders as early as April,” she says.