Premium

Jobs, tenders galore at Mwisho wa Lami

I told Juma the area MP had allocated funds for two classrooms and the ministry had promised two more.

What you need to know:

- Last week, we submitted our student numbers to facilitate funding.

- On Friday, I met the teachers and told them we’d soon be hiring.

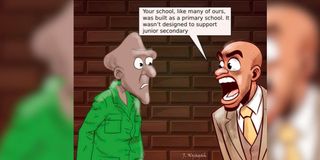

“Running a comprehensive school is nothing like running a primary school,” were the first profound words Juma, a former deputy and now the Head of Institution at the largest comprehensive school this side of the Sahara, told me when I visited him to seek advice.

“That’s why we are called ‘Heads of Institutions,’ not just headmasters or mistresses.”

I told him I didn’t see much difference — it sounded the same to me.

“Oh Dre, there’s a BIG difference!” Juma exclaimed, waving his hands dramatically. “As a headmaster, you’re just managing teachers, mostly ensuring they submit lesson plans and don’t lose chalk. But as Head of Institution, you’re running more than one institution, a whole ecosystem — teachers, students, parents, BOM members, and all the drama that comes with it.”

I told him I wanted to transform Mwisho wa Lami into a beacon of academic success.

“It’s not like we aren’t successful,” I said quickly, not wanting him to think I was drowning. “I just want us to deliver exceptional success.”

Juma leaned back and nodded sagely: “Your school, like many of ours, was built as a primary school. It wasn’t designed to support junior secondary.”

“Exactly!”

“So, if you want to succeed, Dre, you’ll need to upgrade your infrastructure,” he said. “When I talk about building capacity, I mean two things: classrooms and teachers.”

I told him the area MP had allocated funds for two classrooms and the ministry had promised two more.

“That’s a great start,” Juma said. “But let me warn you: if you don’t play your cards right, you might lose one or even all of them. You need to navigate the politics carefully. MPs, ministry officials, even the mamas selling mandazi outside — everyone has interests.”

Juma then gave me a crash course on diplomacy, sacrifice, and survival in the labyrinth of school administration.

“You’ll need to work with everyone, Dre. The MP, the county and sub-county education officials, and the MCAs, name them. Sacrifice a principle or two if you have any—it’s for the greater good!”

He would tell me about his experience building four classrooms for his school.

“It was not easy, but I did it so well that the MP wants to add two classrooms to my school!” he said.

He went on to discuss resources.

“Schools here are under-resourced. You said you only have two JS teachers. That’s a joke. You’ll need to hire BOM teachers or risk becoming a JoaS instead of JS!”

I wondered what JoaS meant.

“A Joke of a School,” he said, laughing.

“But where will I get the money?”

“You can either collect it from parents — if you want to become the most hated head in this region —or come up with creative fundraising ideas. Either way, you need to convince the ministry that you’ve got enough teachers to justify their support.”

Juma also warned me about ministry inspections.

“Expect frequent checks to confirm your teacher numbers. Be ready to get creative. Offline, I’ll share some tricks.”

He then coached me on hiring BOM teachers.

“Advertise on the school notice board but make it as invisible as possible. You don’t want 200 people applying for three positions, especially if they’re all related to influential people.”

“That doesn’t sound like it follows the rules,” I said hesitantly.

Juma shrugged.

“Rules are for guidance, Dre, not to be followed to the letter. Keep the ad up for a few hours. Let the people you want to hire know in advance so they’re ready.”

He suggested I make the qualifications ridiculously high—KCSE C+ and above, a degree, postgraduate qualifications, fluency in at least one foreign language, and a minimum of four years’ experience.

“Where will I find such a person?” I asked, bewildered.

“That’s the point!” Juma grinned. “You don’t want 200 people applying. The fewer, the better. Make sure the qualifications scare off most applicants, leaving only those you’ve already planned to hire.”

“Also don’t just ask for any subject. Like Kiswahili, English, you know, almost every graduate teacher has those. Avoid languages and ask for sciences,” he said

“What if it is languages I want?” I asked, confused

“Looks like we are not communicating. Haven’t I just explained that? Even if you are looking for a teacher for Kiswahili, for God’s sake, please advertise physics! You can quietly amend later.”

He handed me a sample ad he used and added, “Remember, Dre, life doesn’t give you many chances to shine. Take advantage. Classrooms are not built every year. Usitoke bure.”

Last week, we submitted our student numbers to facilitate funding. On Friday, I met the teachers and told them we’d soon be hiring.

After the meeting, every teacher came to suggest someone they knew.

“Let them apply. The process will be open and fair,” was my standard answer.

“Good luck, Dre! I hope utanikumbuka pia,” Juma wrote on SMS yesterday.

I told him I won’t forget him.

The teacher ad will go up today at 2pm and stay until 9am tomorrow. The construction tender will be read next Wednesday.

If you’re interested, apply.

And please — don’t call us. We’ll contact you!