Premium

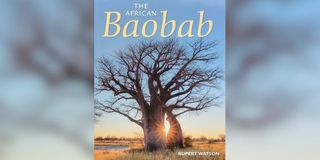

Telling the story of the African baobab

In his book, Rupert Watson describes how an individual baobab is a community of plants, animals, reptiles and insects.

What you need to know:

- In his book, Rupert Watson retells some of the myths that explain why the baobab looks to be such an upside-down tree.

- He describes how an individual baobab is a community of plants, animals, reptiles and insects – what he calls a ‘forest in itself’.

I first came to Kenya by boat, and so did my car – one of the best I have ever owned, a red Ford Cortina GT.

Of the first drive from Mombasa to Nairobi, two images are still clear in my mind. One is of a lone elephant standing close to the road as I was passing Tsavo East.

I was thrilled but not surprised, because I was looking out for elephants.

But what did surprise me were those massive upside-down trees, with bare branches that look like roots and a girth that competes with the height.

Baobabs have continued to fascinate me. I see them as, like the elephants, truly African. I see them as symbols of something important for much of the African continent – the resilience that is needed in a harsh and unpredictable environment.

So, it has been a great pleasure reading Rupert Watson’s second edition of his ‘The African Baobab’ that has just been published.

Rupert trained as a lawyer in the UK; he has practised as a lawyer here in Kenya; but I reckon the work he loves best is studying and writing about natural history.

Evolved formidable resilience

Preparing for both editions of this book, he has travelled in all regions of the continent where baobabs are found – east, west and south. He has closely observed many of the trees; he has done his reading about them; he has told their stories.

Recently, I have been experimenting with the AI application, ChatGPT. I know that if I asked it to write about the characteristics, the distribution and the uses of the baobab tree, I would get, instantly, well-structured information, gleaned from articles, papers and books available up to a couple of years ago.

But you wouldn’t get the presence – the thoughts, feelings and wit of a writer. And you do get all those things with Rupert Watson.

In the introduction to his first chapter, Rupert elaborates on the theme of resilience: ‘Baobabs are living monuments, the oldest natural things in Africa, outliving every plant and animal around them. These trees have evolved formidable resilience in order to survive in some of the driest, rockiest areas of this continent.’

Rupert also retells some of the myths that explain why the baobab looks to be such an upside-down tree.

It was the first tree that God created, the story goes. After a while, it complained that it wasn’t as tall as the surrounding palms. So God made it taller.

It then complained that it didn’t have flowers like the flame trees. So God gave it flowers.

Medical and nutritious uses

When it complained that it didn’t have fruit like the fig trees, God got so angry that he pulled up the baobab by its roots and thrust it down into the ground head first.

In the chapters that follow, Rupert justifies why he calls the baobab a tree of Africa, as everywhere else it grows it seems that seeds have drifted on the waters or have been carried on ships.

He discusses how the trees’ short-lived flowers are pollinated, often by bats; then how their seeds are dispersed, often by baboons. He explains the threats to survival, as human populations expand and baobabs have to hang on in dry and rocky terrains.

He describes how an individual baobab is a community of plants, animals, reptiles and insects – what he calls a ‘forest in itself’. He reviews how the trees became shrines for traditional religious practices.

Finally, he celebrates the very wide range of medical and nutritious uses there are for the pith that surround the seeds, the seeds themselves, the leaves, the flowers and the roots.

In this short article, I haven’t done justice to Rupert Watson’s book. All the tales he tells are engaging; the many photographs are superb.

It is available at selected bookshops or from the author on [email protected]. It costs about Sh3,000

John Fox is Chairman of iDC His email is [email protected]