Premium

The promiscuous ruler of our colonial state

The colonial rulers promoted the role of Maharajas in their pursuit of their principle of ‘Divide and Rule’

One feature of British India was the existence of the Maharajas and Nawabs, the latter being the Muslim version of the former – the maharaja being a more popular and frequently used term. In fact, the colonial rulers promoted the role of Maharajas in their pursuit of their principle of ‘Divide and Rule’. Until the British left India – the subcontinent was a patchwork of more than 500 princely states and the princes ruled one third of the country and just over one quarter of the population of India.

The autonomy granted to these native states by the colonial government depended on the size of the state, the treaty negotiated by the British and the princely state and above all by the tenacity with which their forefathers had negotiated the terms of the treaty.

Thus the Nizam of Hyderabad, the Maharaja of Mysore, Baroda and Kashmir had a much greater say in the running of their own state. They were indeed monarchs of all they surveyed but there were also small states which were like specks on the regal firmament. Junagadh, to which I belonged by virtue of being born in Bantwa, was one of them.

Bewitching

‘They were gods to their people,’ wrote Ann Marrow, the British authoress, referring to the princes. ‘They were bewitching, wanton, cruel, generous, lovable, ascetic, charming and hedonistic. They claimed descent from the sun, from the moon and the Aryan tribes dating back centuries before Christ,’ she added.

Romance

This is what Nehru, the first prime-minister of India, had to say referring to their eccentricities in his characteristic manner. ‘I like to believe that this is all true because it lends some romance and enchantment to the drab rule in India’.

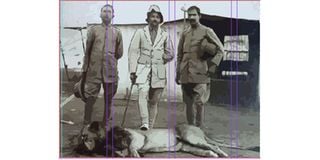

In my view, the princes belonged to a strange breed. They were known to weigh themselves in silver, gold and diamonds to celebrate the length of their reign. Their hobbies included shooting tigers and elephants, and their palatial drawing rooms were embellished with trophies they had bagged.

It must be said to their credit that they contributed greatly to Indian arts and culture, sports and charities. Indeed, they were some of the most colourful personalities of the subcontinent. They were frequently seen on race-courses, cricket fields, tennis courts and polo grounds.

They also built architectural monuments in the form of palaces, temples and mosques. Soon after the protective British rule ended in 1947, Vallabhbhai Patel, the deputy prime-minister of newly independent India, abolished the princely states with a stroke of his powerful pen.

In line with many others of his ilk, the Nawab of Junagadh — Bantwa, my place of birth was a part of it — had both an eccentric and also a promiscuous streak. The former manifested in his love of dogs. His hobby of rearing pedigree dogs was well known in his realm and I heard that when the kennels became unsuitable for his dogs, they were converted as hostel for students of Bahauddin College, built and run by the state where I studied for Inter- science, equivalent of ‘A’ levels now.

Expensive dog-food

It was also rumoured that the dogs were shampooed every morning, fed on expensive dog-food, given exercises and won prizes at international dog shows. When the Nawab’s pet dog and bitch were married at the palace, it was declared a public holiday and when one of his champion dogs died, it was a day of public mourning. One can see the point of what Nehru said!

It was, however, the Nawab’s promiscuity that helped me to concoct a funny story and give a phoney reason for me to become a doctor. The first time I ‘experimented’ with it was in 1968 at my Rotary Club lunch meeting at the ‘New Stanley Hotel’ in Nairobi.

I was asked to give ‘My Job’ talk as a new Rotarian, inducted the previous year. This talk gives a new member an opportunity to introduce himself in his own words, with special reference to his job; it is really meant for him to break the ice with his own Club. It is a 15-minute talk delivered after a sumptuous, three course lunch.

My audience consisted of about 70 Rotarians, most of them septuagenarians, some even in their 80s used to siesta after a few pink gins and a heavy lunch.

I started my speech by saying, “When I was qualifying as a doctor, I was often asked why I had chosen medicine as my career. There were two topical reasons at the time. It was either the missionary zeal of Albert Schweitzer to serve the sick in the hot torrid jungles of Africa or a burning ambition to discover a cure for cancer and collect the Nobel prize in medicine in the rich setting of the Concert Hall in Stockholm.”

As I saw my listeners wilt, I added.”I can’t claim either of these lofty motives. In my case it was the fact that I was born in Junagadh state, ruled by a Nawab. Being Muslim, he could marry only four wives, which he promptly did. To satisfy his wildly polygamous nature, he set up a harem in one of his lavish palaces, where he accommodated about 1,000 concubines of different ethnicity, like a collector’s items.”

My audience was now fully awake, as I continued. “Since antibiotics against sexually transmitted diseases were not available then and it was below the Nawab’s dignity to use anything himself, he appointed a full-time doctor. I met this guy while I was deciding on a career. He described his job in a funny way and said. “The salary is not very high but there are a thousand perks attached to the job!’ As I heard a loud applause, I went on. “My mind was made up; I wanted his job when he retired!”

Malcolm Macdonald, the last Governor of Kenya and Special British Representative to the country, was at the meeting as a Rotarian, and he sent me a letter of congratulation. Typical of the man, never to lose the common touch!