Premium

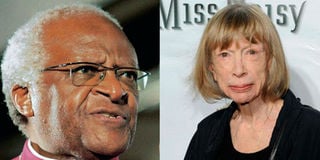

Desmond Tutu and Joan Didion: Double tribute to towering icons

Archbishop Desmond Tutu (left) and journalist Joan Didion.

“In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act. You can disguise its aggressiveness all you want with veils of subordinate clauses and qualifiers and tentative subjunctives, with ellipses and evasions — with the whole manner of intimating rather than claiming, of alluding rather than stating — but there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space,” so once wrote American writer Joan Didion, who passed away in New York on Thursday December 23, 2021.

Three days later, far away and near warmer waters, on December 26, Archbishop Desmond Tutu passed away in Cape Town.

Earlier in her life, Didion had written devastatingly accurate dispatches of a simpler and less desperate time and place when she wrote about 1960s America. She told stories with a languorous, dream-like quality. Like one surveying a scarred land, her prose took a darker turn as America reeled, clamoured and reverberated with disasters, conflicts, failures, fiasco and false starts. Her literary mood shifts in great swoops and glides as she grapples with the vicissitudes of life — sometimes in boisterous, hyperbolic cadences and frantic ebullience and, at other times, her prose was rich in tears and grief.

Archbishop Tutu was the leader of the South African Council of Churches and later became the Anglican archbishop of Cape Town.

At first glance, Didion and Archbishop Tutu don’t seem to have anything in common as the former was a clear-sighted and perceptive writer and the latter an ever-smiling Anglican priest. However, both Didion and Archbishop Tutu had much in common. They both attempted to make meaning out of the puzzled uncertainties of our world. And both took a stand on what they believed in. As Didion explains it, she invaded our most private spaces with her words. On Didion, English novelist Zadie Smith writes that Joan showed her that “a woman could speak without hedging her bets, without hemming and hawing, without making nice, without poeticisms, without sounding pleasant or sweet, without deference, and even without doubt”.

Racial justice

And so was Archbishop Tutu – he stood to be counted even when threats loomed in extravagant menace. Dubbed “an exuberant apostle of racial justice,” he was unequivocal against apartheid in South Africa — engaging in dangerous and extreme close-quarters combat with the powers of the day. He was a brazen risk taker by instinct and a hard charging, hard-driving warrior of social justice and this won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984. After the fall of apartheid, Archbishop Tutu chaired the controversial Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which sought to reconcile blacks and whites. He then became an international crusader for human rights outside his native South Africa.

Both Didion and Archbishop Tutu used words to great effect. Didion is known for her great word choice and her unforgettable sentences. As New York Time’s Frank Burini wrote, “She belonged, in some measure, to the school of New Journalism, which integrated techniques associated with fiction into nonfiction. She had an eye for detail that was a kind of X-ray vision. She had an ear for absurdity no less acute. And her sentences — dear Lord, her sentences! She was… a sorceress of syntax, with a cadence to her words and a music to her paragraphs that were utterly spellbinding.” Indeed, reading Didion could be unsettling; like slipping into a fever.

Archbishop Tutu, on the other hand, used words in spirited oratory and funny parables on the pulpit and in other forums to skewer the set of ideological assumptions under apartheid that whites were superior to blacks; ruffling feathers in the process.

Motivation

Both Didion and Archbishop Tutu became “interpreters of myths”. For Didion, through her pen, she confronted the human experience, especially the questions that puzzled us: mourning, marriage and even migraines and other aches. No matter how dark the matter, Didion would stare at the shifting kaleidoscope of the darkness and come through the other end with some momentary glimmer of consciousness and understanding. She probed shockingly deep into the inner depths of the soul; into what one writer called “the root of the personality, the deep springs of motivation, the dark agonies that produce sleepless nights or dysfunctional days”.

In the same way, Archbishop Tutu was also an interpreter of other people’s feelings; giving voice to the oppressed. A former aide wrote that, “when he speaks he speaks for all — yet he utters the most secret sorrow of your heart.” Like Didion, Archbishop Tutu could reach the depths of the soul and give voice to the heart’s deepest sorrow — thereby becoming a real champion of the downtrodden.

Though both Didion and Archbishop Tutu have now gone to the land of no return, they leave behind legacies of words that will speak to generations to come. As they say in Latin, Venerunt, viderunt, vicerunt —They came, they saw, they conquered.