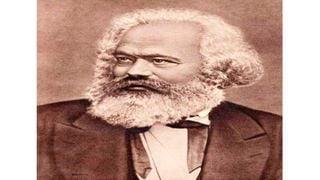

Karl Marx

| PoolWeekend

Premium

The ‘madharau’ mentality, a bane poisoning all our social relations

What you need to know:

- If you turn up at the matatu stand decently and neatly dressed, you are madharau.

- If you are wearing a tie, probably required by your employer, you are madharau.

The ghastly and beastly assault on our motorist sister on Wangari Maathai (Forest) Road on Friday last week shocked all us exposed to it. Mercifully, the law has stepped in and is taking its course, so our comments must avoid prejudicing the proceedings. My take on the incident, however, is that it is a horrid symptom of the growing toxic madharau mentality in our society.

Did you know that you are a madharau? Yes, you are, and if you did not know it, I will show you a few of the many ways in which you are unmistakeably a madharau. This Kiswahili word means “contempt”, “despising”, “looking down upon” or even “arrogance”, and it is in several of these senses that many of your neighbours may regard you as madharau.

If you turn up at the matatu stand decently and neatly dressed, clean-shaven and generally well groomed, you are madharau. If you are wearing a tie, probably required by your employer, you are madharau. The briefcase in which you carry your papers, the glasses you don for your weak vision and the newspaper you carry for your later reading, all these mark you out as “madharau”.

If you speak English, you are madharau. If you speak Kiswahili with a reasonably standard accent, you are madharau. If you drive a car, even if you do not own it, you are madharau. And if you are a woman, in addition to all the other markers above, you are very madharau.

Madharau thus becomes the main epithet for characterising, stigmatising and potentially victimising all those who do not subscribe to the mtaa/ghetto underworld culture that rules such operations as the matatu and bodaboda services. The main players in this class of people have pessimistically defined themselves as the “wretched of the earth”, rejected and despised by organised society, and your encounter with them is fraught with a simmering confrontational negativity.

Social classes conflicts

Logically, madharau should be something you do or show, rather than something or someone that you are. Unfortunately, because of our sharply stratified society into socio-economic classes, you are likely to be presumed guilty of madharau unless and until proved otherwise. You are, thus, madharau, in the eyes of a rival class, because of the class to which you seem to belong.

The reality of different social classes, or statuses, in society dates further back in human history than most of us can project. The reasons for the class differences are also difficult to determine or exhaust. They range from gender through ethnic descent and regional origin to occupational prevalence. Significantly, the classes keep changing as societies evolve.

The main problem with social classes is that they arbitrarily determine the distribution of the economic resources of society. Most of our understanding of social classes in East Africa is based on nineteenth and early twentieth century socialist thought developed by such scholars and practitioners as Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin (a predecessor of Vladimir Putin). These leaders identified the main social classes in their societies as the rich aristocrats, the well-to-do bourgeois, middle class or gentry, the working class or proletariat, and the struggling poor.

In Tanzania where, I was introduced to these ideas, they took these class differences very seriously in their development planning in the early years of uhuru. Their Kiswahili designations for the social classes are mabwanyenye for the feudal aristocracy, makabaila or walala heri for the middle class, makabwela or walala hai for the working class, walala hoi for the struggling poor and mafukara/hohehahe for the destitute poor, also called “lumpen proletariat”.

The 19th-century European socialists noted that there were strong animosities and conflicts among the social classes, especially between the middle class, which controlled the money and the technology, and the working class, which had only its labour to sell, often very cheaply. The socialists called and agitated for a revolution in which the lower classes, especially the working class, would overthrow the middle class and, hopefully, establish a “classless” society.

Concept of familyhood

Socialist revolutionary experiments have been carried out in different parts of the world, but they have often not worked out as well as their advocates had expected. A classic example is Russia and its Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and its satellite neighbours. Its disintegration after nearly a century of struggle has led to several problems, including the current conflict in the heart of Europe.

African socialist-inspired leaders, like Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, believed that the best way to manage our class differences and conflicts was to emphasise the concept of “familyhood” in our societies. Our social and economic circumstances may differ for various reasons. Yet we remain literally related at many levels. Our social classes are not like the castes in some countries, out of which one can never move. This belief in our relatedness (udugu, with no “n”) is what lies at the root of Mwalimu Nyerere’s policy of ujamaa. Other practices, like the umuganda (weekend communal work) of Rwanda, also promote this social unity.

Most of our countries, however, have left our social classes mostly to fend for themselves. Some of us even deny that such classes exist, which is a very dangerous burying of our heads in the sand. You and I, I believe, belong to a sort of middle class. We are really at the centre of the transformation of our societies. We are the lawmakers, the preachers, the managers, the administrators and teachers our societies.

We must lead the fight in pulling up our relatives in the struggling working and destitute ranks. First and foremost, we have to give respectful recognition to those less advantaged than ourselves. Secondly, we have to share with them the faith and tactics of self-improvement. This means engaging them, meeting them at a grassroots human-to-human level.

If we remain egotistically absorbed in only improving our lot, dismissing and avoiding the “walala hoi” and “mafukara hohehahe” as hooligans and outlaws, we will be justifying their dealing with us as perennial “madharau”.

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and [email protected]