Premium

Binyavanga Wainaina’s spirit lives on in new collection of his essays

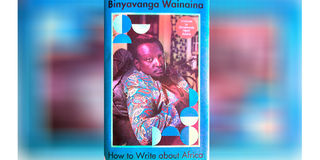

Acclaimed Kenyan author Binyavanga Wainaina.

It is more than four years since Binyavanga Wainaina died. In a world where news hardly lasts minutes, it is easy to forget the dead. But ideas don’t go away as easily.

Some specific experiences with some people long dead can remain etched in our memories despite the passage of time. It is not easy to forget Binyavanga Wainaina if one is from the book world in Kenya. Whether one had read his writing or not, Binyavanga (Binya to his close friends) was not someone to forget easily.

If you hadn’t heard of him, then you would have heard of Kwani? Or been familiar with some of the publications from Kwani? One may have disagreed with the claim by the Kwani? family of writers and followers that Kwani? shook the literary ground in Nairobi in the early 2000s.

However, it would be difficult to dismiss the claim since they indeed drew significant global attention to Kenya’s literature in the 21st century. The Caine Prize for African Writing might be a British award, but for many young African writers seeking to be read beyond the continent, this prize has been an important launchpad.

When Binyavanga won the prize in 2002, Kenya was firmly in the eyesight of the rest of the world. The country had just come out of a long period of a single-party regime. Kenyans were quite enthusiastic about the future. The new government promised socio-economic progress, justice, freedom, and equality, among others.

His story ‘Discovering Home’, could be read as a metaphor for millions of Kenyans who were ‘re-discovering’ their country after many years of injustice under a repressive state. For a young Kenyan who left the country to chase dreams beyond, writing or storytelling delivered him to his people in his country of birth.

Which is why reading the collection of his writing, How to Write about Africa (Hamish Hamilton, 2022; edited by Achal Prabhala), is a ‘re-discovery’ of some sort. First, this collection invites the reader once again into the life of Binyavanga. Here one meets Binyavanga the cook, the restaurant owner, the promoter of African cuisine, the failed-university-student-turned-writer-on-African-foods, fiction writer etc. Binyavanga the kwerekwere was determined to make a life for himself in a country that was waking up from a bad dream of hundreds of years of colonisation. How did a young Kenyan expect to survive and succeed in Cape Town, that very white of South African cities!

But Binyavanga was undeterred. This is where he decided to become a ‘food slut’, as his first published essay on food is titled. Binyavanga sought to introduce African delicacies in Cape Town, a city that was used to foreign foods. Thus, Maembe na Pilipili, Mushy Pea Mukimo, Shingo ya Kondoo na Maziwa Lala, Swahili Braised Chicken, Mutura etc found their way onto the dishes he and his partner made and onto the palates of his customers. Did they say that the way to a man’s (or woman’s) heart is through his (her) stomach! Food remains the most forceful means of bringing together people from different cultures.

Therefore, Binyavanga wasn’t just cooking and writing about people, he was also, literally and literarily, bringing people from different races, cultures, places together.

Equally, stories bring people together. To listen to a story is to literarily eat the author’s creative cooking. No wonder they speak of cooking up a story. For sure, stories are cooked, just like a cook imagines what the eaters of a meal will feel like, the writer has to work hard trying to visualise the audiences’ response to their story.

All of the stories in How to Write about Africa were published before and are publicly available, save for some, which are personal communication between Binyavanga and Achal Prabhala. Yet, rereading them is some kind of an encounter with the author. One is left wondering, how daring was this young Kenyan? How could Binyavanga have dropped out of school in a foreign land? Why did he think that he could become a writer and make a living out of it in a strange place? How daring was Binyavanga to imagine that he could make a living out of cooking? Who put in his head the idea of cooking African food for a people who were unused to it?

What spirit of daring made Binyavanga submit that story to the Caine Prize? How audacious of him to write back insisting that his essay was worth considering? Well, after winning the prize, Binyavanga would become bolder enough to establish Kwani? with his friends? But what made him think that the Kwani? fraternity would change the literary landscape in Kenya, as they claimed?

In other parts of the world, people who dare, the way Binyavanga dared (whether one agreed with his daring or not), are called discoverers, pacesetters or heroes. If there is a single memory that should always be associated with Binyavanga, it has to be that spirit to dare (which sounds fancier than challenge) — dare the establishment, dare culture, dare officialdom, dare the-way-things-are-done-here dictum etc. The essay that gives the book its title was one big dare.

Binyavanga was daring a whole industry, culture, tradition, institutions, communities etc that had produced and retailed a racist stereotype of Africa. How to Write about Africa remains one of the most mocking pieces of writing about representations of Africa by non-Africans and Africans. This essay is probably the most memorable satirical piece on how Africa is deliberately drawn by writers as poor, violent, cursed etc.

But this essay should be read alongside ‘How to be a Dictator’, ‘How to be an African’, and ‘The Senegal of the Mind.’ Only a maddeningly daring writer would have written these three essays alongside ‘How to Write about Africa’.

But having been born of a couple that dared cross ethnic and geographical boundaries in the 1960s; having been born in a country that was hardly a decade from the dark shadow of colonialism in the 1970s; having become a youth at a time when Kenya was in the grip of dictatorship in the 1990s; and becoming aware of the possibilities of freedom and self-advancement beyond his country, Binyavanga had to be an enterprising man to become who he became.

It is his literary and personal audacity that left the memories that one finds in How to Write about Africa; memories that carry the hope that Africans will one day free themselves of colonial thinking and become subjects of a world of humanity.

The writer teaches literature at the University of Nairobi. [email protected]