Gurna’s Nobel win shines bright light on Tanzania’s neglected writing in English

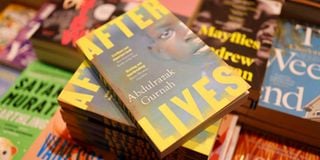

Copies of "Afterlives" by Tanzanian-born novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah are displayed at Waterstones bookshop in central London on October 7, 2021. - Tanzanian-born novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah, whose work focuses on colonialism and the trauma of the refugee experience, won the Nobel Literature Prize.

What you need to know:

- Perhaps more deserving of our readership as we savour the light of Gurnah’s Nobel achievement, is Tanzania’s works in English.

- Traditionally, Tanzania is the cradle of Kiswahili and literature in the same language has been its chief cultural export.

A day after UK-based Tanzanian author Abdulrazak Gurnah was declared this year’s winner of the prestigious Nobel Prize for Literature, I strolled into a few bookshops in down town Nairobi hoping to get a glimpse, if not a hold, of at least one of titles that have brought him instant fame. My inquiries, however, drew blank stares from the staff who had apparently not heard of such a writer, let alone the titles he has written.

Yet this is someone from our neighbourhood down south whose name and photograph international media had beamed to the whole world as winner of the most coveted award and whose penmanship of the ten novels, numerous short stories and essays they described in superlative terms.

A mini vox-pop survey in my modest social circles and a question tossed to some individuals, likely to have encountered the writer in their lines of duty or adventure, equally did not yield much. The majority of their responses began with the refrain, “To be honest with you…” or, “To say the truth…” as they pleaded not having read the man.

So, who is this old man said to have been born among us, in the jumuia of East Africa, fled for refuge in teen age, stumbled into writing aged 21, studied, wrote, taught and won a literature gold prize in retirement without as much a mention in our daily gossip?

Of course, the Swedish Academy that sponsors and manages the Nobel Prize works in mysterious ways. Its criteria is a top secret that has raised widespread suspicion and accusations of subjectivity in awarding the prize as the awardees.

For a while, we have waited for the Nobel gurus in Stockholm to name someone from our midst like Ngugi wa Thiong’o or such other household luminaries as M.G. Vassanji and Nurudin Farah. Then they surprise us with someone not previously speculated, at least publicly, as a possible contender for the prize in the region. Did the Nobel Prize Committee discover him for us?

Gurnah's well-earned fete

The brief bio accompanying the media stories of his Nobel victory is as brief as poem and comes with a rhyme: He was born in 1948, fled Zanzibar aged 18, and arrived in Britain in 1968.

But this is not to begrudge Prof. Gurnah his well-earned fete. Those who have read him affirm that he really deserves the award. An article, Tanzanian Anglophone Fiction: A Survey, by John Wakota lists Gurnah as a leading diasporic writer in Tanzania alongside Moyez G. Vassanji who lives in Canada. Their works, he says, enjoy canonical status inside and outside Tanzania as part of a national, regional and indeed continental canon.

The Nobel Prize Committee chaired by Anders Olsson described him as one of the most prominent post-colonial writers. Author Giles Folden dubbed him one of Africa’s greatest living writers.

Writing in Conversation Africa, Lizzy Attree hailed the Nobel literature prize as the biggest single prize purse. She says winning it puts a global spotlight on a writer who has often not been given full recognition by other prizes, or whose work has been neglected in translation, thus breathing new life into works that many have not read before and deserve to be read more widely.

Perhaps more deserving of our readership as we savour the light of Gurnah’s Nobel achievement, is Tanzania’s works in English. That it had to be a writer of English fiction from Tanzania, more so, Zanzibar, is quite telling.

Traditionally, Tanzania is the cradle of Kiswahili and literature in the same language has been its chief cultural export. We grew up on a diet of rich Kiswahili poetry, plays and novels by eminent writers from Tanzania like Shaban Roberts, Ebrahim Hussein and Mohammed Said Abdula.

Unexplored literary potential

What has been less talked about is the contribution of Tanzanian Anglophone writers in the region said to have been grossly ignored in studies about East African fiction. As a result, says Wakota, Tanzania people know more about other canonical African novelists than their very own Anglophone writers.

According to Wakota, the invisibility of Tanzanian English fiction is not due to the country’s inability to produce good quality Anglophone novels but challenges in accessing the texts both within and outside Tanzania.

One can discern that Tanzania teems with unexplored literary potential in English. In his award declaration statement Olssen says of Gurnah: “His work gives us a… picture of another Africa not so well known for many readers…”

James Carrey writes in Africa Writes Back of a similar observation that Prof. Molly Mahood College at University of Dar es Salaam made when she “discovered” a potential writer of fiction in English.

In her letter to African Writers Series (AWS) of Heinemann Educational Publishers Mahood chimed, “I think I have found a good Tanzanian writer… very impressed by the drive and energy of his writing… It seems to me the first novel from Africa that really tries to get into somebody’s mind… It gives the European reader a surprising insight into the life and customs of the Nyakyusa tribe of South Western Tanzania.”

This discovered writer was Peter Palangyo, a biology teacher-turned diplomat, whose novel Dying in the Sun was published in 1968, just as Gurnah was settling in the UK and nursing homesickness that led to his own writing.

So, who else will the Nobel Committee discover for us when the angel of Prize sails to our shores next time? Might we need to bet beyond “the usual suspects?”

Mr Kibet is an editor in Nairobi. [email protected]