Premium

International Mother Language Day and formula of celebration

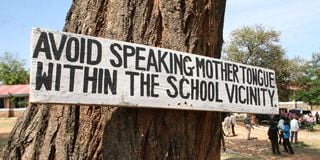

A notice pinned to a tree at Sangach Primary School in Marakwet East discourages speaking in mother tongue at the school.

“Ibutu maber (did you spend the night well)?” I greet you, as we do in Lwoo/Luo in Northern Uganda. You should answer, “Abutu maber (I spent it well)”. That is our belated celebration of International Mother Language Day, observed Wednesday this week, February 21.

I trust that you celebrated it with all due enthusiasm and decorum, by at least greeting in your home language those around you with whom you share this treasure.

Note that I said “home language” rather than “mother language”. This is because the “mother” label, attractive and emotive as it is, is sexist and also misleading in strictly scientific linguistic terms. First, it is discriminatory.

Whether you say “mother” or “father” language (or tongue), you are discriminating against one gender or the other. Secondly, we in sociolinguistics label a person’s languages in the chronological order in which he or she acquires them. Thus, we speak of a person’s first language, second language, third language and so on. In any case, one’s first language is not guaranteed to be the first language of one’s father or mother.

A person’s first language will most likely be the language most frequently spoken in the home and in the speaker’s immediate environment, whether that is Ekegusii, English, Kiswahili or Sheng. This is the awareness behind my proposition of the cautious term “home language”.

The term is, of course, also suggested by the Kiswahili concept of “Kinyumbani”, the popular label, especially in the Tanzania of my youth, for our indigenous languages. Indeed, I think it is the indigenous languages that the UN wants to highlight on International Mother Language Day, and they should adjust the name to suit the concept.

Another snag with the “mother language” label is that its sentimentality contradicts the scientific fact that language is a social, acquired skill. It is not “sucked from our mother’s breast”. A Chinese child raised in an entirely Luhya-speaking environment, even if suckled by a Chinese mother, will speak Luluhya as its first language, and will not find it any easier learning Chinese than any other Luluhya speaker.

These hard-headed observations point towards the main proposition I wish to make about our indigenous languages as we celebrate them at this stage in our history. My proposal comprises three interrelated parts.

First, we should approach our indigenous languages with an objective, well-informed attitude. Secondly, we should engage trained linguistic professionals in the development of our linguistic resources. Thirdly, we should lucidly and actively formulate and implement our language policies.

Regarding objectivity and rationality about our indigenous or home languages, as opposed to being emotional and sentimental about them, I am the first to admit that this is the “problematic” of language. A problematic is a serious complication which we acknowledge in a situation but to which there is no obvious solution. The only way to deal with a problematic is learning to live with it. A language, as linguists tell us, is a system of conventional vocal symbols used in human communication. Basically, a language is a means or a tool for exchanging information.

The “problematic” with the linguistic tool is that, despite the urging of linguists like me, we cannot help getting emotionally and passionately attached to our languages. This is partly because it is these very languages that convey our deepest feelings, desires, fears and aspirations to our fellow humans. But there are also the very profound psychological associations and attachments that we develop to the sounds, vocabulary, inflections and other structures of our languages as we use them. It is from these depths that poetry and great creative literature arises. Thus, you get people longing to operate in the languages in which their forbearers “lived, laughed, loved and died.”

That said, however, we must face the fact that languages are social and historical artefacts. They rise, thrive, change, and even sometimes die, in line with the changing social and historical circumstances around them. A language is considered to be dead when its last known speaker dies. Thus, many African indigenous languages have died and are dying because of the sociohistorical forces around them. Among the forces are foreign invasion, colonisation, urbanisation and globalisation.

Yet we cannot let these treasures disappear without a fight. Experts tell us that every language system is a storehouse of indigenous knowledge, including scientific knowledge, and the loss of any language is a loss of the specialised knowledge it stores. Moreover, the UN has told us that one’s native language is a fundamental human right. This is where the effort of everyone who cares comes in. Languages live and thrive through usage. It is up to us, the users of the languages, to make sure that they are proactively and increasingly used in all possible contexts, like speech, education, writing, media and cyberspace.

This is no mean undertaking, and it will require three main ingredients. The first is a systematic and general sensitisation of our populations to the value and legitimacy of our languages in all our development processes. This should include a concerted attack on the colonial hangover assumption that serious business can only be transacted in colonial languages. Secondly, we need a large and strong squad of skilful and well-trained linguists who should research, plan, formulate and spearhead the practical implementation of a policy of multilingual communication that does not disadvantage any of our languages.

Finally, African leaders and governments must have and show a genuine political will and commitment to progressive language policies. We hear many good things being said about our languages, as we did last Wednesday in many of our capitals and cities. But the sweet talk is often not followed up with effective practical action on the ground. I, for one, am still puzzled by the apparently indefinite “delay” by Uganda and Kenya to set up National Kiswahili Councils, as recommended in the protocols that set up the East African Kiswahili Commission.

Incidentally, Kiswahili, too, is a “mother language” to many in East Africa.

- Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and literature. [email protected]@yahoo.com