Notre Dame, Victor Hugo and a galley-slave of French literature

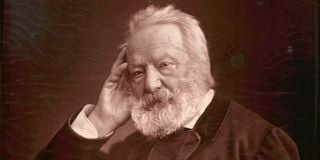

French author Victor Hugo.

Let us take a brief trip to Paris as you consider congratulating me on an “achievement” of which you had not heard. Paris is always a “happening” city, and 2024 has been yet another year when all roads literally led there. Our most glorious memories of Paris 2024 will of course be the Olympics, where Faith Kipyegon and her colleagues crowned us with indelible golden laurels.

Your congratulations to me, however, would be on a different aspect of Paris. This is the majestic Notre Dame (Our Lady) cathedral, which reopened just under a fortnight ago after a five-year restoration epic, following a disastrous fire incident. I expect congratulations because, curiously, I received deep condolences from a very good friend when news of the cathedral’s devastating fire spread over the media in mid-April 2019.

My friend’s sympathies surprised me because I really had no close personal links to the world-famous edifice. But on second thoughts, I realised that Peter’s feelings for me were justified, in view of my pretensions to French “langue et civilisation”, as our French professors offered it to us in our undergraduate days. I might have told you that my language major in my linguistics-language-literature (LLL) combination was neither English nor Kiswahili but French.

Indeed, upon graduation, my career could have taken either a French or an English direction. I was, in fact, offered admission to the elite Parisian “Ecole Nationale Superieure d’Administration” in 1970. But I did not go, because of the intense pressure from the Makerere English/Literature lobby, of which I told you some time ago.

Living legends

I, however, retain a keen and respectful interest in French and the best aspects of French and Francophone culture. Needless to say, my closest attachment is to the writings of the Afro-Caribbean greats of the 1940s-1960s, like Senghor, Laye, the four Diops (Alioune, Anta, David and Birago), Ousmane, Mariama Ba, Ranaivo, Rabamenanjara and the Caribbean Frantz Fanon and Aime Cesaire. These and many others were living legends of Francophone creativity, scholarship and leadership when we were growing up.

Inevitably, however, our French studies included a significant clutch of native French works cutting across the centuries. From the many authors I voraciously devoured or studied in my academic prime, I randomly remember many that I got to admire and like. Among these are the Renaissance humourist Rabelais, the ponderous essayist Montaigne and all-time comedian Molière. Of the poets, Lafontaine, Baudelaire, de Musset, Valery, Verlaine and Alphonse de Lamartine pop up.

Among the prose writers my favourites include Voltaire, Dumas, Verne, de Saint-Exupery, Camus and Gustave Flaubert. Flaubert taught me the importance of the “inevitable word ” in creative writing. Maybe I should also mention Honoré de Balzac, the stupendously prolific novelist that the French refer to as the “forcat” (galley-slave) of their literature. Balzac wrote compulsively and incessantly till his death, caused by coffee poisoning, as legend has it.

Linguistic theorisation

The reminiscences here transport me back to my hectic late 1960s and to the lecture theatres, seminar rooms and libraries of the Universities of Dar es Salaam and Tananarive (Antananarivo), Madagascar, where I was introduced to all this fascinating stuff. Moreover, this was in addition to the English (and African) Literature onslaught and the tough linguistic theorisation of my beloved mentors, the late Mohamed Abdulaziz and Wilfred Whiteley.

Did I tell you that, to add to my French credentials, I directed, in French, a play, Le voyage de Monsieur Perrichon (Mr Perrichon’s Holiday) with my undergraduate colleagues in Dar es Salaam? Starring the late Clement Maganga, and with me in one of the lead roles, we received quite enthusiastic responses in Dar and, later, in Madagascar, if I remember rightly, with the encouragement of our Dar teacher, Dr Pierre Legofic.

Clement Maganga, who taught with distinction at several universities in East and West Africa, was one of the founders of the Kiswahili Department at Dar University. He is best remembered for translating Mariama Ba’s So Long a Letter into Kiswahili.

But back to Notre Dame, the French author who is my main connection to it is Viscomte Victor Hugo. Hugo is recognised as one of the exponents of the French literary Romantic Movement, which flourished mostly in the nineteenth century. This movement was a reaction to the overly formalistic rationality that dominated French thought and creativity in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

French Romanticism advocated spontaneity and individuality as opposed to the rules and formalities of the previous age. French romantics, like Hugo, projected emotion over reason, emphasising intimacy and free, unfettered exploration and expression, with the human being immersed in raw nature. Romanticism sought to reach for the sublime and infinite depths and heights of experience.

Ideals of romanticism

Hugo was ardent in his pursuit of the ideals of romanticism, even in the face of fierce opposition. The first performance of his play, Hernani, in 1830, was disrupted by opponents who felt that romanticism was decadent self-indulgence. His “novel”, Les Miserables, in its earnest effort to advance romanticism, ended up being one of the longest prose works in the French language.

But Victor Hugo’s most direct connection to the great cathedral is his narrative called, just that, Notre Dame de Paris (Our Lady of Paris). In it, a physically deformed bell-ringer at the cathedral struggles to save a gypsy young woman whom some hypocritical men threaten to burn as a witch. The plotters’ intentions are in fact to disguise or revenge for their rejected lustful advances towards the woman, Esmeralda.

Quasimodo, the bell-ringer, offers Esmeralda shelter in the towers of the Notre Dame cathedral. You can see the subtle imagery here, as the gypsy woman herself becomes “the lady” (dame) of the cathedral. A beautiful movie of this story was made by Disney some years ago, and should be available somewhere online. It is called The Hunchback of Notre Dame, one of the English translations of Hugo’s title.

Meanwhile, if you are in Paris one of these days, go over and have a look at the rejuvenated Notre Dame. It, like the other great medieval cathedrals of Europe, is a testimony to the strong faith of those who built it, with what we would regard today as rudimentary technology.

Christmas would, indeed, be a good time to go. You would most probably hear “Il est né le divin enfant” (he is born, the divine infant) sung or pipe-organed there.

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and literature. [email protected]