Breaking: Autopsy reveals how Cyrus Jirongo died

Premium

Portraits of success: How inspiring are these books?

What you need to know:

- The lustre of the civil service may have faded for some like Betty Gikonyo and Maina Wanjigi as they answered the call of business but the dream of excelling as a career technocrat has been the goal of others — like Martin Oduor-Otieno.

The spate of (auto)biographies published recently begs the question of function. What are we to do with all these personal stories?

Why should the story of how one Kenyan made it from the village to the university in some glamorous city matter to the rest of us? And where is the story of those who never left the village?

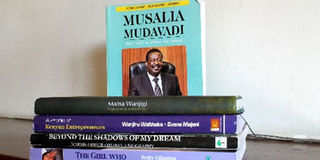

My arguments stem from the last five (auto)biographies that I have read — Betty Gikonyo’s The Girl Who Dared to Dream; Martin Oduor-Otieno’s Beyond the Shadows of My Dreams; Maina Wanjigi’s Shepherd Boy In Search of Virtue; the Musalia Mudavadi story as told by James B. Shimanyula in Man with a Vision for Kenya and A Profile of Kenyan Entrepreneurs by Wanjiru Waithaka and Evans Majeni.

The value of (auto)biography as history is undeniable. Personal histories of this kind become public undertakings because they help us to (re)construct the dominant aspirations defining a society from one generation to another.

Kenyan biographies demonstrate that access to education has been deified as the single most important ingredient for success. The pioneer generation sought colonial education solely as a means to a career in the civil service and that became their ticket to exponential transformation.

A job in the civil service came with a modern house, a bicycle or car, fashionable modern clothes and, maybe, a tendered garden. These trappings of modernity were necessarily interpreted as success.

Though they represent two different generations, the stories of Maina Wanjigi and Betty Gikonyo follow this essential path, underpinned by the ethos of leadership ingrained in both of them at their respective Alliance high schools. In the case of Maina Wanjigi, a stint in the civil service opened the doors to entrepreneurship.

At independence, the authority of the civil service emanated from the depth of knowledge embedded within it. Pioneer civil servants like Wanjigi played a big role in crafting government policy on land, agriculture and commerce.

With that fore-knowledge, Wanjigi was able to make investment decisions that became staggering successes, like Carbacid Limited, a Sh20 billion industry that supplies compressed carbon dioxide to food manufacturers in East and Central Africa. Transitioning from business to politics, Wanjigi initiated many communal business ventures in Kamukunji constituency.

Betty Gikonyo’s dream of becoming a doctor like her elder brother, Wallace Kahugu, drove her to excel at school and qualify to study medicine at the University of Nairobi (UoN).

Her stint in the civil service did transform the material quality of her life but by the time she had completed her post-graduate training in the early 1980s, the standards of excellence in the civil service had declined considerably. Her greater success, therefore, is seen to have come through private practice.

Presumably, the formula for success in her generation was not just in accessing education, it was dependent on qualifying in the professions — medicine, law, engineering and so on — and moving beyond the civil service.

Betty ultimately combined professional training with entrepreneurship. Establishing the Karen Hospital against huge financial odds is a remarkable story.

Unwittingly, perhaps, it unveils the mixed blessings of marrying a classmate who is within the same profession. But it also demonstrates that there are still sure-footed, brilliant men out there who are not afraid to let women rise, flourish and shine.

The lustre of the civil service may have faded for some like Betty Gikonyo and Maina Wanjigi as they answered the call of business but the dream of excelling as a career technocrat has been the goal of others — like Martin Oduor-Otieno.

He shone at school and university; was employed in the private sector; distinguished himself enough to be called up to the “Dream Team” that was assembled by the then Head of the Civil Service, Richard Leakey in 1999 to bring the rigour of the private sector to a government that was dogged by mediocrity. Martin later returned to the private sector, rose further up the corporate ladder and led Kenya Commercial Bank for seven years.

Stories of rural to urban migration via school paint a fairly linear formula for success in the yesteryears — hard work and sacrifice to excel in the local primary school; get admission to a national school; secure a place at university; graduate and get a good job. Is this still tenable?

And what of those who were born into a middle-class urban existence, what exponential transformation have they sought? What is their template for super-achievement?

The question is not just how people sustain wealth, it is also a question of how a head-start in life can be turned into a multiplier effect that ups social benefits for the majority.

These are difficult questions to answer because of the restraint with which the subject of an urban middle-class heritage is invariably handled in Kenya.

The reality of the vast majority has been the village-to-town template; overcoming poverty and marginalisation. Consequently, it is this version of the tumetoka mbali narrative that has gained credence as the authentic marker of our heritage.

The exclusions inherent in this master narrative create a false dichotomy. Poverty does not encompass every life outside Nairobi. Additionally, urban life is not a seamless stream of affluence.

Marketing a story

Martin’s battery of biographers have marketed his story as one “from the humble origins of village life in a slow and laidback lakeside village”. But Martin grew up in provincial privilege, driven to school by his father and cushioned by the securities of the Catholic Church.

In Musalia’s case, Shimanyula struggles to impose a tumetoka mbali narrative and does a really poor job of recreating the socio-cultural texture of the urban era in which Musalia was raised.

What did living in Kileleshwa in the 1960s and 1970s mean in the scale of city life? What was the philosophy of schools like Nairobi Primary and Nairobi School where Musalia was educated and how has that ethos served him in later life?

Navigating residential areas and schools that were only very gradually peeling off the colonial colour bar demanded certain social skills and a very fluid cultural disposition. Surviving those schools was in itself an achievement. Not everybody did.

The disavowals by these biographers are regrettable. The story of where children — like Martin and Musalia — who grow up with educated working parents derive their hunger from is one that needs to be heard if we are to succeed in re-defining success and amplifying socio-economic mobility.

With its strong focus on templates for wealth creation, A Profile of Kenyan Entrepreneurs does a better job of interrogating questions of inherited privilege and succession planning.

It interrogates failure as much as it documents success. Each one of the 13 entrepreneurs profiled narrates a humbling debacle. And they all provide useful lessons on innovation and self-actualisation.

Manu Chandaria was born into a family of successful traders. But by the time he finished his engineering degrees in America, family fortunes had dwindled considerably.

He could have walked away from his father’s struggle to make Kaluworks Limited profitable and secured a good job in the civil service or in a private corporation.

Manu chose, instead, to consolidate his engineering skills with the family’s experiences in commodity trading. He learnt from their failures and he grew by studying his context and its needs.

The Chandaria formula for consolidating success entails – education in designated professional fields in the best schools in the world; hands-on training in the family businesses; support to the next generation to venture out into new territories; philanthropy and community service.

Manu’s Midas touch also comes from his people skills. Knowing how to handle his competitors in Uganda back in the 1960s was not learnt in any school. It is a blend of the humility, acumen and appreciation of people’s needs that have also furthered his philanthropy.

Evidently, honing leadership skills is as important for a politician as it is for an entrepreneur.

Entrepreneurs debunks a few other myths about what it takes to attain affluence and to become a leader. From the story of Ibrahim Ambwere, the real estate mogul of western Kenya, we learn that education is not the sole catalyst for success and the city is not the only place to make money.

Building a town

While young men were streaming to the city in search of work, Ambwere left a lucrative carpentry business in Nairobi in 1959, moved to rural Chavakali and built a town. And when his children proved unable to manage his vast business empire, he revised his succession plan by marrying a third wife to help in expanding his horizons.

Nelson Muguku, Kenya’s largest poultry farmer, teaches us that making money does not have to be glamorous. Muguku left a dignified career as a teacher in 1957 to rear chicken, a job that was traditionally left to the young girls in the homestead!

Mogambi Mogaka debunks the myth of life in the diaspora as the hallmark of “making it”. In 1992 when the Kenyan economy was spiralling to its lowest, Mogaka went against the trajectory of settling to white-collar employment in the diaspora after a good education. He came back to Kenya, avoided the capital city and went off to transform commodity pricing in Kisii.

From Myke Rabar of Homeboyz Entertainment we learn that a hobby can yield serious money. His passion for music was so contagious that it absorbed his brothers and grew into a multi-million shilling family enterprise.

The stories of Mary Okello and Esther Muchemi are different from that of Betty Gikonyo. Mary and Esther did not simply extend the operations of their professions; they branched out into entirely different industries and revolutionarised them. Remaining within the line of your original training is not the only formula for success.

Failure to access credit is usually the point at which most ventures collapse. Jonathan Somen came from a privileged family but did not have banks falling over themselves to give him credit.

He looked to his family to pool their resources and invest in AccessKenya, which has since grown into a leader in the ICT industry.

The biographies of B.A. Ogot and Joseph Maina Mungai can help us evaluate the substance of a career in academia but from reading Entrepreneurs, it is already apparent that the tension we usually create between making money and generating knowledge that transforms lives positively is the ascetic vanity of the ivory tower and some of those who call themselves intellectuals.

Life writing is growing significantly in Kenya but untold stories abound. The forthcoming biography, Women in Public Spaces, from Dr Wambui Kiai and her team at the UoN will fill a significant void. Still, we need reflections that will offer other definitions and measures of success beyond money and status.

Additionally, a lot needs to be done to improve the literary quality of our biographies. Often the style borders on didactic motivational speaking and a preachy, self-righteous tone where sombre reflection complete with regrets and misgivings would work better to inspire the reader.

For instance, Betty Gikonyo’s religious beliefs intrude on her story with a fervour that threatens to seriously diminish the size of her readership.

When people write biographies before the November of their lives, theirs is more than an exercise in catharsis and reconciliation. We saw how Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father aided his political career. It is not uncharitable to say that Musalia’s biography was written with this kind of outcome in mind.

Musalia’s Dilemma

The only problem is, it does not get to the essence of Musalia. There isn’t even a mention of his life-changing dilemma, at 29 years, when he had to choose between what was fast becoming a successful career as a real estate valuer at Tysons Limited and the political pressure to take over the Sabatia parliamentary seat upon the death of his father. What tipped the balance? Have there been any regrets?

Shimanyalu’s book has value as an abridged political manifesto detailing Musalia’s campaign trail in the run-up to the 2013 General Election.

In similar fashion, the timing of Martin Oduor-Otieno’s biography reminds us of the teachings of the Chinese Cultural Critic, Rey Chow: “treasures of the past are most valuable when they are pawned for more pressing needs of the present”.

Biography can be a powerful self-advertising brochure. It is also a source of information and inspiration that can, properly used, help to build a national culture of enterprise and excellence.

Dr Nyairo is a cultural analyst. [email protected] Twitter: @santurimedia