Premium

Reuben Nzioka Mutua, the forgotten hero of prison reforms

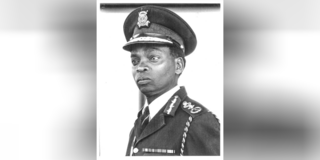

The former Commissioner of Prisons, Mr Reuben Nzioka Mutua. He died in Nairobi on May 26, 1986 following a road accident.

As Kenya prepares to celebrate its 60th Madaraka Day, the country reflects on the heroes and heroines that have shaped the modern nation.

While some of these leaders are well-known and have been honoured in past independence commemorations and other occasions, some are less known and their immense contributions risk being lost in the fog of the country’s collective memory.

One such leader was Reuben Nzioka Mutua, the second African Commissioner of Prisons. In his time, Mutua was famed for his principled stance and singular dedication to duty.

An upcoming biography of the man, Commitment, Diligence and Faithfulness, depicts him as having been so principled that he was one of the few civil servants who could stand up to then all-powerful Minister for Constitutional Affairs, Charles Njonjo.

Mutua defied Njonjo numerous times despite the latter’s larger-than-life role in government. The most notable case was when he declined Njonjo’s bid to irregularly release a murder convict. He thrice defied Njonjo when the minister instructed him to include the convict, Benson Mbugua Kariuki, in the list of those earmarked for presidential amnesty in 1981.

A report by the Weekly Review in March 1984 during the judicial inquiry into allegations that Njonjo had planned to overthrow President Moi, which is cited in the forthcoming book, provides a glimpse into Mutua’s rare principled stance.

The book narrates how Moi was duped into releasing Kariuki, on Jamhuri Day of 1981. Moi was to release 2,172 petty offenders but the name of Kariuki — who was serving 10 years for murder — was sneaked in at the last minute, bringing the number to 2,173.

Mutua had flatly refused to obey Njonjo’s order to release Kariuki before he finished his prison term and the minister had to use other people to insert the extra name on the list. According to the book, the insertion was so clumsy that the typeface was visibly different.

At that time, civil servants and ministers feared Njonjo, who had amassed great influence by dint of having been instrumental in putting Moi in power.

Kariuki, a coffee farmer, had been convicted of killing his estranged girlfriend, Elsie Muthoni Njau, who had cancelled their planned marriage.

On March 16, 1977, Kariuki went to Njau’s house in Nyeri to reconcile with her but found her with Police Inspector David Kamau. He whipped out his pistol and shot Kamau twice.

Kamau managed to escape, whereupon Kariuki turned the gun on Njau and shot her twice in the forehead. Kamau was the main witness and claimed that though he had known Njau since 1967 he was not her lover. The judge sentenced Kariuki to death.

Kariuki appealed and the sentence was reduced to 10 years for manslaughter.

The inmates Moi was to release were those that did not have more than six months to serve as of November 20, 1981, and must have served at least a third of their sentence.

The cover of the book Commitment, Diligence and Faithfulness by RN Mutua.

Prison commanders submitted their lists to Mutua, who in turn compiled a master list. The name of Kariuki — who was in prison at Kibos, Kisumu — was not on the list.

Mutua’s efforts to stick to the law were thwarted when Njonjo — who was also the minister in charge of prisons — inserted the name of Kariuki.

Mutua’s stickler-for-rules mien in the office extended right into his home. He would never allow his children to be taken to school in government vehicles. Some of his children remember being ferried to school and back in Mutua’s derelict Peugeot 204, which was prone to sudden breakdowns.

Mutua would also not allow his children to report to school with anything from government stores; not even a pen or pencil, preferring to send them to a kiosk on the way to school to buy whatever they needed.

In a humorous story that his wife Teresia told the couple’s children, on the day that Tom Mboya’s cortege was to pass through Nakuru, Mutua (then the Rift Valley provincial police officer) stood at the door and politely cautioned her; “No matter what you hear in your office today, don’t come out to the streets.” He then left for work, with his day entirely focused on containing the riotous crowds of mourners.

Teresia, more out of curiosity than defiance, immediately stepped out of her Standard Chartered Bank office to get a feel of the action. She said that as soon as she was outside, a policeman in camouflage hit her on her knee with a club so hard that she could only crawl back to the office for cover. When Mutua returned home that evening and saw her limping around the kitchen, all he asked was, “Did you go to the place I told you about?” She did not say how she responded.

Born in Kiitini sub-location of Kalama location in the then Machakos District in 1932, Mutua attended government schools in Machakos and then proceeded to Maseno in Nyanza Province before joining the police force as an assistant inspector in 1955. He rose through the ranks to senior assistant commissioner of police in charge of Central Province.

Mutua’s eldest daughter recalls her father telling her that he had to harvest sisal leaves, beat them into twine and sell them to raise his school fees. He also learned, from a young age, to hitch rides on trucks over 400km from his village to school in Maseno.

Because of his personal experience, Mutua had a very high regard for education and made sure he educated not just his children but also siblings, nephews and nieces.

In 1977, President Kenyatta promoted him from provincial police officer to Commissioner of Prisons, the first cross-service deployment for the Kenya Prisons Service. He succeeded Andrew Saikwa, the first African to hold the post after independence in 1963.

Mutua is remembered for bringing changes that made Kenya’s correctional facilities more humane. During his eight-year tenure, he introduced compulsory training for warders and oversaw significant reforms in the prison system, including improving conditions, introducing vocational training programmes for inmates, and implementing measures to reduce reoffending rates.

His long tenure in the Prisons Service earned him the nickname Mutua wa Magereza (Mutua of Prisons). Mutai died on May 26, 1986 following a road accident. He was driving to Nairobi from his Emali home with his wife when his Peugeot 504 collided with another car near the present Jomo Kenyatta International Airport and Mombasa Roads junction. He died at Nairobi Hospital two days after the accident while his wife survived it with injuries.

President Moi eulogised Mutua as a loyal and patriotic Kenyan who cared for the welfare of others. The then Attorney-General, Mathew Guy Muli, described him as an officer who worked with humility.

Moi rewarded him with an offer to buy land in Emali in recognition of his contribution to prison reforms. It was on this property that Mutua was buried at a funeral attended by the then Vice-President Mwai Kibaki.

Mutua exemplifies what can result from clarity of purpose, dedication to duty and integrity of character for public servants.