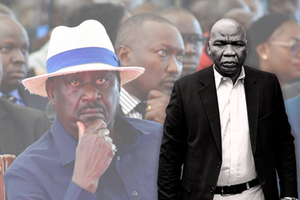

The late George Oduor has been a part of Jaramogi's and Raiila Odinga's family since the late 80's.

“Danding Cojuangco (an associate of President Ferdinand Marcos of Philippines and the head of San Miguel Corporation) arrived an hour late, escorted by his security team. Coca-Cola had security around Keough, the company president. Members of the two security teams were eyeing one another nervously, since they were all carrying weapons… Imelda Marcos (the first lady and wife to President Marcos) decided to join us at the hotel, arriving a shortwhile later, her security team in tow. Now we had three security teams operating independently… A few minutes later… someone dropped a metal chair on the parquet dance floor. I saw the security guys reaching for guns. Imagined a shootout involving the president of Coca-Cola, the head of San Miguel, and the first lady of the Philippines. The end of my career flashed in front of my eyes. It took a few seconds — it seemed like thirty minutes to me at the time — for the security teams to realise it was only a chair and to put down their weapons. It was a very scary moment”.

These words by Neville Isdell, a former Chief Executive Officer of Coca-Cola, on a 1985 trip to the Philippines, highlight the work bodyguards do and the split-second decisions they make that can mean life or death — with hearts racing, blood pounding in their temples and hands firmly on the triggers of their guns. One of the people who lived this nerve-racking reality was former Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s long-time bodyguard, George Oduor, who died on Wednesday, April 2, 2025.

Mr Oduor’s gaze around Mr Odinga was stern and as hot as an invisible sun. In his job, Mr Oduor, like other bodyguards, relied on his training. This vigilant training is highlighted in the book, In the Secret Service: The True Story of the Man Who Saved President Reagan’s Life by Jerry Parr who in 1981 was the bodyguard standing next to President Ronald Reagan when John Hinckley, Jr., stepped out of the crowd, and aimed his gun at the president. The president was shot but probably had his life saved by the quick-thinking Parr and his colleagues.

Parr writes that “For the first week after President Ronald Regan’s inauguration, every time the president left the safety of the White House, I stuck so close I could smell his aftershave… I could sit behind him to survey the room. I had a good eye, trained to see trembling hands, darting eyes, sweat on the forehead… a disturbed look on the face… clothes or shoes that didn’t fit in… a bulge in an overcoat… a purse clutched a little too tightly”.

Mr Oduor probably also relied on something else less tangible: a soldier’s natural instinct to smell danger.

Lawyer Silas Jakakimba said that Raila cried over the phone while speaking of Oduor’s death. Maybe Mr Odinga remembered joyous evenings with Mr Oduor by his side. Or maybe the times they looked at the stars in the sky at night — clusters of galaxies as far away as their dreams. Or maybe the long-forgotten smells came back: the familiar scent from an afternoon in Mr Odinga’s days as a young politician, the curve of the open sky, the odour of invisible but persistent flowers, fallen leaves, old leather mixed with the smell of various cereals — a confused mass of images conjuring a world in which Mr Oduor was by his side, a world now gone for good.

Mr Oduor saw Mr Odinga handed back and forth by fate between opportunity and risk — from Mr Odinga’s days as Member of Parliament to failed presidential candidate to Prime Minister to folk hero and Kenyan tsar — sometimes gruff and impulsive but always energetic. Mr Oduor found himself at the forefront as a silent observer of Kenyan history unfolding before him, especially the bareknuckle politics with its scratching, clawing and backstabbing. Unfortunately, he has gone before writing his memoirs. An African proverb says that: “When an old man dies, a library burns”. It feels like a library has burnt down.

Had Mr Oduor written his memoirs, they would probably have been entitled, “Standing Next to History: Protecting Raila Odinga — the Enigma of Kenyan Politics”. One of the chapters would probably be devoted to the close shaves when Mr Odinga’s life was in danger and what Mr Oduor did. Mr Oduor’s memoirs would have been riveting.

Memoirs are “a collection of memories that an individual writes about moments or events, both public and private, that took place in the subject’s life”.

There are several reasons why Kenyans should write their memoirs. The first one is preserving one’s legacy. Memoirs allow individuals to document their lives and “share their experiences with future generations, creating a lasting legacy”. Mr Oduor’s memoirs would have narrated to future generations what it was like to protect Mr Odinga.

The other reason for writing memoirs is to pass wisdom and life lessons. Most memoirs are written later in life after people have amassed a lot of experience in the business of living so they can advise others on what worked and what didn’t work.

May more Kenyans write their memoirs. We owe it to future generations to do so.

The writer is a book publisher based in Nairobi. [email protected]