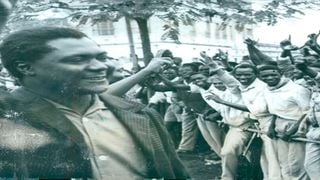

Tom Mboya greets his supporters after winning the election in 1963.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Celebrating 65 years of the political mischief ahead of general elections

You must have heard by now that the proposed changes to Political Parties Act is to favour Raila Odinga’s Azimio la Umoja. Now, let me take you through a short 65-year historical sojourn and you will realise that politicians belong to the same forest – and are only after their own survival.

The first beneficiary of political chicanery in Kenya was the grandmaster of electoral politics, Tom Mboya - and that was before independence. For those thinking that the ongoing drama over Political Parties Bill is a matter of life and death, please, don’t sweat the small stuff for every election comes with its own package of mischief. I would have been surprised if we never had.

Let’s start from the beginning in 1956 when Mboya returned from Ruskin College and found that his nemesis Argwings-Kodhek had taken over Nairobi with his Nairobi District African Congress. While Mboya wanted to vie for the Nairobi seat, the electoral laws, put in place while he was away, dictated that one must have higher education evidenced by either a degree or diploma.

Mboya did not have such papers – and did not have either of the other attributes spelt by the electoral law. He had not served in the military or in civil service for a continuous seven years, his salary was not above £240 a year and was not above 45.

With Mboya out, on a technicality, the colonial government realised that the man they hated as a block, Argwings-Kodhek, would be the ultimate victor. As Kenya’s first African lawyer, Kodhek’s oratory and nationalist manifesto and his pro bono defence of Mau Mau freedom fighters had earned him friends and enemies in equal measure.

Electoral laws

By the time Mboya announced his candidature on December 6, 1956, political pundits were rather surprised how he would navigate the electoral laws. But a week later, the government hurriedly pushed through the Legislative Assembly an amending ordinance that now redefined education to also include a scholarship offered at tertiary level if the candidate had finished the course. Mboya had in 1955 received a scholarship to study Industrial Management at Ruskin College, Oxford – a small institution which gave adults with little or no education some training.

As Mboya’s biographer, David Goldsworthy later noted in the book Tom Mboya: The Man Kenya wanted to Forget, ‘presumably the government framed the amendment with Mboya specifically in mind, though its motives can only be guessed.”

It was this election that saw the election of Mboya in Nairobi, Oginga Odinga (Nyanza Central), Bernard Mate (Central), Daniel arap Moi (Rift Valley), Ronald Ngala (Coast), James Muimi (Eastern), Lawrence Oguda (Nyanza South) and Masinde Muliro (Nyanza North) as members of Legislative Council (LegCo).

Before the elections, Mboya is thought to have engineered a coup within Kodhek’s Congress party with notable defections to his side and which included Kodhek’s ‘suspension’ as Secretary General of his party for ‘gross misconduct’.

While Mboya went on to win the Nairobi seat, it is sad that both died six months apart in 1969: Kodhek from a mysterious road accident along today’s Argwing’s Kodhek Road in Nairobi and Mboya from an assassin’s bullet. And that marked the end of Kenya’s two most promising leaders.

But before he was killed, Mboya had helped ruthlessly manipulated electoral and party laws (some quarters say he was used by Kiambu mafia) in order to tame Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. So frustrated was Odinga that in 1966, when a plot was hatched to dilute the position of Kanu vice-president with the creation of regional vice-presidents, he quit his position and formed the Kenya People’s Union.

While the law allowed one to simply cross the floor without an election, the way Kadu members had done in 1963, the electoral law was swiftly changed stop any further defections to KPU. It was the defection of Achieng Oneko on April 25, 1966 that annoyed Kenyatta. Next day, he told a Kanu Parliamentary Group meeting that anyone who had defected should be expelled from Parliament. But Speaker Humphrey Slade told Jomo that this was unconstitutional, and nobody had such powers. It was Mboya who proposed that the Constitution should be amended to have those who defected seek new mandate from the electorate. On April 28, Parliament was re-called, and the amendment rushed through the House. It is still with us today.

Both Charles Njonjo and Mboya would be back in the House in December 1966 seeking to abolish the Senate which was, on the floor of the House, labelled ‘a nuisance.’ Parliament was told that this was being done to foster unity instead of engaging in “futile disputes that turn the Assembly into a talking shop”, according to Njonjo.

Capitalism

The only opposition came from KPU with Mr Odinga warning that unity cannot be achieved through capitalism. “The right road for Kenyans to achieve unity was that of Socialism. Things were not okay in Tanzania until president Nyerere found that the road to unity was the road to socialism.”

Odinga warned that the abolition of Senate would only empower Jomo Kenyatta to do what he liked when Parliament was dissolved. “The president was already the head of government, head of state, and head of Kanu. To give one man all these powers might be alright at the present time but in future might prove to be a mistake and could land the country in a lot of trouble.”

Odinga was right – and with the death of Senate, there was no one to offer any more checks. It was during the heated debate that Njonjo was likened to Hitler by Kisumu Rural MP Tom Okelo-Odongo after Njonjo had used the same phrase ‘futile disputation’ which was once used by the Nazi leader when referring to British Parliament.

In order to lure the MPs to pass the Bill, the Act extended the life of Parliament by two years from June 1968 to June 1970 and thus they got a two-year extension. All this was pushed by Mboya, the mastermind of election laws.

Another electoral mischief and which was personalised was on the Kenyatta succession. In 1964, both Mboya and Njonjo had helped to change the presidential succession laws by providing that if the president died, the National Assembly would pick one of its own for the balance of the term. There was fear that Jomo might die in office and in such a scenario, Jaramogi would become the president. Thus, this law was another bid to lock out Jaramogi from the Kenyatta succession. For when, Jaramogi left – and Kenyatta appointed Daniel arap Moi (after Joe Murumbi’s resignation) – the law was changed again giving the Vice-President six months as interim president before an election.

With Odinga and the Senate gone – and with Moi under the wings of Njonjo – the next obvious manipulation of electoral laws centred on the presidency. There was fear that Mboya – after Kenyatta had a heart attack in July 1966 – was eyeing the seat and might command the numbers. Another threat was from the populist J.M Kariuki, the Nyandarua North MP. In March 1968, a constitutional amendment was done giving the vice-president a six-month period to act before a presidential election. It was this clause that would later fuel the Change-the-Constitution movement in 1976, which was aimed at stopping a possible Moi presidency.

But the anti-Moi group was outsmarted and outfoxed by the Njonjo-Kibaki axis which supported the Moi presidency. Later, the two would be the first to fall: Njonjo in 1983 and Kibaki in 1988 when he was demoted from Vice President.

In May 1982, after former Kitutu East MP George Anyona had called for the return of multi-party democracy, it was both Njonjo and Kibaki who rallied the MPs to unanimously pass the constitutional amendment. Kibaki moved the procedural motion reducing the publication of the Bill from 14 to six days. He said the idea was to guard Kenyans “against confusing agents.” The Bill was moved by Njonjo and the rest is history.

Nomination

Some of the notable electoral bad manners took place in 1988, when Kanu was the sole party, was that if one got 70 per cent of the votes during the nomination for the March elections, the person would be declared unopposed. It later emerged that those who controlled the counting also controlled the outcome. This way, Moi was able to control who got elected leading to bitter fallout and new clamour for multi-party in 1990.

With the demands, and political upheavals, Moi not only agreed to pluralism but also the formation of the Electoral Commission of Kenya which had constitutional powers. This was led by retired Chief Justice Zaccheaus Chesoni who was appointed by President Moi together with his commissioners.

A push by the civil society from 1990 to level the electoral ground was abandoned by the politicians and while they were sure to beat Kanu it was clear they did not mind the powers enjoyed by the presidency under the old Constitution. A similar scenario emerged in 1997 when rather than change the Constitution to guarantee free and fair elections the MPs supported the Inter-Parties Parliamentary Group (IPPG) which locked out civil society from any further deliberations. They passed the minimum reforms laws – only again to be beaten by Moi.

Our history is littered with so much political chicanery ahead of elections that it is now hard to discern what is in the interest of democracy – and what is purely driven by politicians personal agenda. We have had our fair share of gerrymandering, a politicised map-making process, and electoral laws crafted for short term benefits of either an individual or a political party.

It is now 65 years since the original Mboya mischief of 1956 and it is only when you look at the bigger picture that you see the game plan.

So, my fellow Kenyans, don’t sweat the small stuff about the drama in Parliament over Political Parties Amendment Bill. All those politicos, fighting, yelling, and dancing on the respectable floor of the House are birds of the same feathers - same WhatsApp group. They are fighting to survive. (Happy New Year!)

[email protected] @johnkamau1