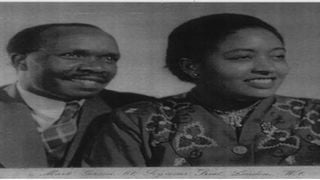

Henry Muoria and his wife Ruth during their early years in exile. They were the editors of colonial era publication Mumenyereri.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Celebrating the story and legacy of pioneer radio girl Ruth Muoria

What you need to know:

- The story of Ruth and her family helps us understand the social, political and economic progress of Kenya during the early years.

- Ruth was either a child of love or fate. Ruth’s grandmother, Pricilla Gikiro, had escaped a bad marriage in the rural Kikuyuland and settled in the then Masikini slums, an unplanned settlement in Nairobi.

When she left Kenya in 1954, and at the height of colonial emergency, Ruth Muoria was in her twenties – a young bride following celebrity journalist Henry Muoria who was also on the run.

Had her husband been in Kenya, and just like Mbiyu Koinange who also fled, he would have been a perfect trophy by the colonial government which was eager to nail down the elites behind the freedom struggle.

By the time she died on January 6, 2021 in London, Ruth, Henry’s third wife, had somehow been forgotten though her story has vividly been captured in the seminal work: Writing for Kenya; The Life and works of Henry Muoria which was written by her daughter Wangari Muoria-Sal, Cambridge University historian Prof John Lonsdale, Bodil Frederiksen of Roskilde University and Derek Peterson, a professor of African studies at the University of Michigan.

The story of Ruth and her family helps us understand the social, political and economic progress of Kenya during the early years – and especially the role of women born in the slums of Nairobi. It is both a gender story and a story of challenges and this, too, has been recounted by Dr Frederiksen, the scholar who first decided to put into perspective the Muoria family story and set of a series of publications.

Born Ruth Nuna in 1927, her father was an Asian trader named Jan Muhammed – the first generation of Asian traders who had arrived in Nairobi to seek fortune in the emerging town. It was in this new Nairobi town, that her mother Grace Njoki had been brought up as one of the first generation of African women who grew up in Nairobi town. Ruth was either a child of love or fate. Ruth’s grandmother, Pricilla Gikiro, had escaped a bad marriage in the rural Kikuyuland and settled in the then Masikini slums, an unplanned settlement in Nairobi. But this, together with a Swahili village named Mombasa, were closed down in favour of Pumwani and as the government started the £13,000 African public housing scheme at “Kariokor ”.

Middle class

In Pumwani, the women residents were allowed to build their own houses – and Luise White, in her book The Comforts of Home: Prostitution in Colonial Nairobi, argues that prostitution here was tolerated by the government although it was hard to distinguish between ‘urban relationships’ and sex for sale. But the Muoria family, which later grew here, would tell Dr Frederiksen that this was “a respectable and socially mobile middle class living with an emphasis on education and with women forming the hardworking core.” It was in this jungle that Ruth was brought up as her mother sold beer and let rooms that she had inherited from her mother Pricilla.

Life in Nairobi, as she would later recall, did not favour the girl-child. She was unhappy that despite her desire to get education she won’t be given the chance. Her mother still took her to school and she was taught ‘spinning and weaving’ and would later feature in some radio programmes, thanks to her Swahili, about baby care.

By the age of 19, she was already married off to a Goan, had a daughter and divorced. “He was not my tribe,” he would later say. It was on her way to her radio job that she met Henry Muoria – one of the most prosperous African publishers in Nairobi. By then standards, Muoria was rich: he had two cars, land, a permanent brick house, two wives and several children.

Ruth had many suitors and her mother was shocked that her daughter, brought up in town, had agreed to become a third wife and settle in the village. But Muoria had promised her that she won’t allow her to work on the farm.

By this time, Jomo Kenyatta had returned from his long sojourn in Europe and was criss-crossing the country revitalising Kenya African Union, the first nationwide political party. Muoria, by then Kenyatta’s Press Secretary, was in turn taking advantage of the rising interest in politics and his newspaper had become popular. Muoria once asked Kenyatta what will be the indicators that the British were getting ready to grant Africans freedom. And Kenyatta replied: “Those indicators will only come about when they start arresting a lot of our people and putting them in prison. It will also be proof that our people have really worked hard for what they believe to be their legitimate rights.”

Poverty

Both Muoria and Kenyatta had some semblance. Dr Frederiksen, in one of his papers, compares Muoria to Jomo Kenyatta: “Both began their working lives as herds boys in the southern part of Kikuyuland not far from Nairobi and were driven to the city by curiosity and poverty. They were mission-educated moralists and Kikuyu cultural nationalists.

They were polygamous patriarchs and entered into unions with highly independent and gifted women. Both were energetic entrepreneurs, and writing was one of their enterprises. They edited Kikuyu newspapers and perfected their writing skills in Britain.”

But their lives took different paths and had swapped their exile positions. A known pamphleteer, Muoria not only wrote and edited the radical Kikuyu biweekly publication Mumenyereri, but had also set up his own printing press selling upward of 10,000 copies. He was also the publisher of the radical Kikuyu political songs which had borrowed their melody from famous English hymns such that political messages would be passed disguised as Christian songs.

In his book, Defeating Mau Mau, Louis Leakey seemed astounded by the songs which could safely pass for common hymns: “If (colonial administrators) heard a large, or a small group, singing to the tune of ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ or any other well-known hymn, they were hardly likely to suspect that propaganda against themselves was going on under their very nose. They would be more likely to consider that a Christian revival was on its way.”

The songs had been published by Mumenyereri Printing Press which was supporting Kenyatta’s efforts to build KAU and also bolster the radical wing at Kiburi House, Nairobi.

So flourishing was this enterprise starting 1945 that by the time the emergency was declared in October 1952, Muoria was in London, and for just a month, seeking to purchase a modern printing press. His second wife, the Makerere-trained Judy continued to publish Mumenyereri, by then a biweekly. “She would travel to Nairobi, organise the printing material that Muoria had sent her, and get the paper out,” wrote Dr Frederiksen, a university scholar who has been studying the Muoria family.

Political upheavals

The emergency – and the political upheavals that ensued – then split the family and brought to a halt Muoria’s budding career as a publisher. It is said that before Judy was detained, she managed to transport the printing press to Nyathuna village in Kiambu where it had been for many years as a family totem.

Perhaps due to her mixed parentage, Ruth managed to reach Pumwani with her children and settled in Makadara. Muoria was by this time worried about the fate of his children and wives. He was also lonely in Europe where he could not get a job as a journalist. They said to get a job, you had to be a member of a trade union and to be a member of a trade union you must have a job.

To eke a living, he settled to a job he had abandoned in Nairobi: railway guard. It was demoralising. Luckily, Ruth managed to sell one of Muoria’s car, secure a passport and join her husband in North London where they settled with Henry who was now working as a London Underground train guard.

With Ruth by his side, Muoria continued writing – but never succeeded in publishing his thoughts. But his autobiography, I, The Gikuyu and the White Fury was published in 1994. In the book, he quotes Kenyatta acknowledging his role. “If I did not find a man like Muoria when I arrived back home from England, who came to meet me at Mombasa and wrote down what I told our people there in my first speech, who took the trouble to follow me home and wrote down what I told our people up and down our country in various meetings, and who published all those speeches in his newspaper, Mumenyereri, I would have been by now a forgotten man busy tending my farm at Gatundu.”

Muoria, in turn credited Ruth for his success. But by the time she died last week, in London, Ruth had actually been forgotten in Kenya – save for her celebrity status by scholars who are still keen to study the politics of Henry Muoria and the role of pioneer women in the freedom struggle.

[email protected] @johnkamau1