Premium

Let’s encourage debate on university financing

Last minute rush: Students and parents return forms to the Higher Education Loans Board offices in Nairobi. Public universities in the past thrived on parallel degree programmes to raise cash.

Public universities are opening their doors to first-year students as the government rolls out a funding model touted as a game-changer in higher education. It is, however, a moment for tough decisions. Uppermost in the minds of students and their parents is securing funding.

Second is the courses the students will pursue, given the persistent practice of placing many in programmes they never chose, forcing them to spend their college years agonising about their career paths.

The central issue, though, is funding. Higher education financing is being transformed in a manner that is causing disruptions in the supply and demand chain.

From the outset, it must be acknowledged that transforming university funding is inevitable. The existing model has been overtaken by time and is unsustainable. Introduced in the 1990s under the Structural Adjustments Programmes, the model was based on a lower capitation level and fewer student population. The dynamics have changed.

The funding plan launched in May is based, among others, on the following principles. Every needy student should get access to full tuition. Two, allocation to students is graduated based on needs. Three, courses should be charged at the market rate to enable universities offer quality education and four, ensure universities operate with financial stability.

Based on these and from the supply side, public universities have introduced a unit-cost financing model, charging the courses at market rate and pushing that to students. The immediate effect is a steep rise in fees. Ideally, this should have happened a long time ago, but was always shelved for fear of the backlash from students, parents and the general public. This is why, though the universities introduced a Differentiated Unit Cost (DUC) financing model in 2016, the government bore most of the costs – 80 per cent – while students paid a small fraction.

DUC failed because of inadequate funding and delayed disbursement to the universities, pushing them to huge debts.

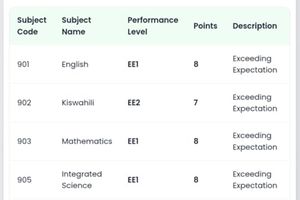

The new model categorises learners into vulnerable, extremely needy, needy and less needy. Concomitantly, scholarships and loans will be differentiated, with students from vulnerable and extremely needy backgrounds getting generous scholarships compared to the others.

Assessment for the scholarships and loans will be based on family socio-economic background, affirmative action and household composition and size.

This is a marked departure from the age-old practice where all students who qualified for university and were admitted through KUCCPS automatically got funding.

On paper, this sounds great but in practice, it cannot be guaranteed because of financial and administrative challenges.

Evidence is emerging that students have encountered numerous challenges when applying for funding. Accessing the University Funding Board portal, providing the requisite details and complying with the requirements has proved problematic. As at the end of last month, only 75,272 students out of 285,167 had successfully applied for scholarships and loans.

The second challenge is financial. The government has not provided sufficient allocation to meet the needs of all qualifiers. Although the government increased allocations to the Higher Education Loans Board (Helb) for bursary and loans, it is inadequate. In the current financial year, the government set aside Sh30.3 billion to Helb, a significant increase from the previous Sh15 billion, but it still leaves a funding gap of Sh18 billion.

It is these shortcomings that compelled Education CS Ezekiel Machogu to issue an order to public universities to admit all freshers without fees. Last week, the Cabinet also waived a requirement that a student must have a national identity card to secure funding. These are commendable but demonstrate the concern all along that the plan had not been properly thought through.

Which leads to the question, what should we do to create a sustainable funding model for universities?

The first step is to diagnose the real problem with funding and prescribe the correct medicine. The second is to fix logistical and technical hitches that surround the application and processing of scholarships and loans. Third is increased funding to Helb.

Beyond this, focus should shift to the universities and spur them to think carefully about their sustenance and stop depending on the Treasury. The practice across the world is that universities raise money to remain afloat.

In the past, universities thrived on parallel degree programmes to raise cash from fee-paying students, but that fizzled out.

Universities are hubs for ideation, research and experimentation and knowledge production – great endowments they ought to leverage on to raise funds. But this hardly happens. Paradoxically, many lecturers run successful consultancies and research projects but at individual level because the universities do not have institutionalised structures for those. Time is now to create structures for institutional consultancies, research and projects.

Scientific research leading to patents should take centre at the universities. Similarly, the institutions should engage in practical research that provides solutions to the nation’s challenges. It is questionable, for example, why the universities offer courses in agriculture but cannot help the country through research to attain food sufficiency.

Universities should also review their programmes and cut out those that are redundant, duplicated and obsolete, rethink their cost structures and rationalise expenditure, including trimming staff.

While acknowledging initiatives to revitalise university through new funding approaches, pertinent challenges persist. Thus, debate on university funding has to continue until sustainable models are attained.

Mr Aduda is a consultant editor. [email protected]