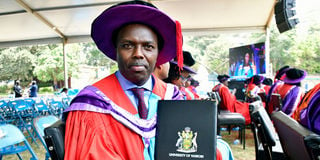

Keiyo South MP Gideon Kimaiyo graduates with a PhD in International Relations at the University of Nairobi on September 20, 2024.

Keiyo South MP Gideon Kimaiyo says as a young boy he vowed not to get married until he had completed his PhD.

The 37-year-old has now kept half of that promise. On Friday September 20, he graduated with a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in International Relations at the University of Nairobi's 71st graduation ceremony, and he can finally think about becoming someone's husband.

“In this department, we are graduating seven students (on Friday September 20), and Gideon is one of them. So, I’m very proud of them; they have worked very hard,” said Prof Patrick Maluki, the chairman of the Department of Diplomacy and International Studies at UoN, who also taught Mr Kimaiyo.

How Mr Kimaiyo won an elective seat as a bachelor is one of the twists in the story of an otherwise shy man with boyish looks and three master's degrees.

Is there someone waiting to fly him out of the waiting bay of self-imposed bachelorhood, when he should have had "at least seven" children by now, according to the standards set by his peers in the village?

He laughs at the question and chooses not to answer.

“But you’ve stayed true to your promise?” we ask.

“Yes, I’ve kept my promise,” answers the MP, who is serving his first term.

Does that mean he can now marry, even if it’s this Saturday?

“Hata kama ni hiyo Friday jioni (I can even do it on Friday evening after graduating),” he shoots back, laughing.

When I was going into politics, people said I wouldn’t be elected because I wasn’t married; that I should look for someone and do a quick wedding. I said 'No',” he says.

Keiyo South MP Gideon Kimaiyo being conferred with a PhD at the University of Nairobi on September 20, 2024.

To further illustrate how principled he is, he says he was not circumcised until he had completed his secondary education.

While most boys undergo the rite of passage in their early teens, he did so much later. This was not without its disadvantages, as he was often confronted with the derogatory word “ng’eta”, given to boys who had not undergone the ritual.

“What can a ng’eta tell us?” was a common question.

He decided to postpone circumcision because he did not want to follow the usual path for boys in his area. His reasoning was that it would do little to lift him out of the crippling poverty in which his family lived.

The sixth of nine children, he came from a homestead that sold alcohol, and there were many days when he would go home for lunch to find people enjoying their tipple but with nothing to eat because their parents were too busy to think of preparing a meal for the children.

But selling alcohol did little to lift the family out of poverty. So he decided to postpone his initiation.

“Mostly, when young people get circumcised, they start drinking alcohol (as they consider themselves old enough) then get married at a young age. I made a promise to avoid these,” says Mr Kimaiyo.

Growing up, something didn’t sit right with him about the way boys got wives very early in their teens and started big families with meagre resources.

“(If I didn’t choose a different path) I would be married with maybe seven children, because the rest of the guys (my age mates) are like that in the village, struggling with life like everybody else,” he says.

In an interview with Nation.Africa hours before he transitioned from “Mr” to “Dr”, the lawmaker described the highs and lows of his education journey. It was never pretty.

This is a man whose father used to pay his secondary school fees in kind by delivering milk. This was at Kiptulos Day Secondary School. He joined the school after leaving Tambach High School.

After completing his Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) exams at Kaptarkok Primary School in 2000, he was admitted to the iconic Tambach, which has produced many big names in the Rift Valley.

The only amount he ever paid as fees at Tambach was Sh8,000, which was raised through a fundraising campaign as he prepared to join Form One. By Form Three, the fees had accumulated and a change in management spelled doom for him when a principal who understood his plight left the institution.

He had to move to a day school.

“My fees were paid through milk, which my father was supplying daily to the school,” he says. “It was used for making tea in the school.”

He sat his Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) exam in 2004 and scored a B. He needed a B+ to go to university.

“After high school, I taught at Kaptarkok Primary School (his former school) as a volunteer teacher for two years. During this time, I tried to apply to several colleges. They gave me admission, but I could not proceed because of lack of fees,” says Mr Kimaiyo.

In September 2006, he was admitted to Kenya Utalii College. When he travelled to Nairobi for admission, he had nothing but Sh2,000 given to him by his former head teacher, Mr Luka Rotich. His uncle took him in and allowed the young man to try knocking on many doors.

“The reporting date was September 28. I reported with nothing, and I mean nothing—not even personal belongings. I lied to the admission officers that my parents had issues with their bank account; that all would be sorted out the following week,” he says.

Keiyo South MP Gideon Kimaiyo being conferred with a PhD in international relations by University of Nairobi Chancellor Patrick Verkooijen during the institution’s 71st graduation ceremony on September 20, 2024.

This was meant to buy time for him to get the fees. He tried numerous times to get an audience with Nicholas Biwott, the area MP at the time, and when he finally met him after several attempts and dead ends, he pleaded his case and Mr Biwott gave him Sh35,000 to secure his admission at Utalii.

He remembers being given Sh35,000 in cash by Mr Biwott’s personal assistant William Chepkut, and rushing to bank it.

It took weeks for the fees to be paid, and it was out of sympathy that he got a place at Utalii, long after other students had settled in.

“I was very lucky that in Utalii, you eat in the institution. You also get a mattress, a blanket, everything,” he says.

With contributions from relatives, he managed to get through the first year, but it was a mammoth task to pay the fees for his second and final year. Mr Biwott had been voted out of office in the 2007 general election, and things couldn't get any easier.

The family had to sell land.

It was hard to convince his siblings, but he made a promise.

“My father had to sell land. And I had to convince all my siblings that I would repay it. You can imagine how hard it is to convince someone in the countryside who hasn’t gone very far education-wise. I also had to convince them that if we sold the land, they would get a cut; I wouldn’t take all the cash. That’s how they accepted,” he says.

Selling the land meant he could pay his school fees for the whole year and his final exams.

“My college education was done. I promised myself to work hard. I was the best in my class. During graduation in Utalii, they usually have prizes. I scooped almost all of them. I would be called to the podium again and again,” Mr Kimaiyo recalls.

After Utalii, he worked as a travel agent, earning a modest salary that did not allow him to travel home often. He mostly lived with his cousin.

And just as he was about to leave for Finland in search of better opportunities, he secured a well-paying job at Kenya Airways.

The upward trajectory began.

He remembers spending his first salary to get electricity to his home.

Since then, he has bought land and built houses for each of his older siblings and sponsored the education of each of his younger ones. His younger sister, for example, had to return to standard eight after more than 10 years, even though she already had children, and is now a master's student working with the government.

“I’ve bought everyone land and built (each) a house; so all are okay,” he says, adding that he stopped the brewing and sale of alcohol at their home.

Mr Kimaiyo also sponsored the education of his nephews and nieces in an attempt to rewrite the family's history. He later extended this to other children in the area.

“How did I gain my fame? Well, I gave back to the community. I didn’t invest anything in myself. The only investment I have is my education. I don’t own land, I don’t own (anything else). I own my education,” he says. “When it came to the election, it was so easy for me because they had seen [what I had done for the community].”

From the diploma he earned at Utalii, he has since upgraded to a bachelor's degree from Moi University (tourism management), a master's in business administration (MBA) from UoN, and another master's from the United States International University-Africa (international relations).

He started his PhD before the 2022 general election campaign intensified, and took a break to take another stab at becoming Keiyo South MP, having come second in 2017. This time he hit the jackpot.

Mr Kimaiyo said he has made education a key priority in his leadership, ensuring that day schools are truly free, securing scholarships for every student who scores more than 350 marks in the KCPE exam, and seeking higher education opportunities for scores of learners.

“For me, it starts with education and ends with education. We have used education as a source of inequality instead of as a source of equity, where whoever can take their child to a private school has a higher chance of going to … university,” Mr Kimaiyo said. “If education was a source of equity, it could have helped the weak.”

Mr Luka Rotich, his primary school head teacher, told the Nation that Mr Kimaiyo had risen from obscurity to become a role model.

“He has done a lot. He is seeing far education-wise, and if he continues like this, we’ll have many people who will get help,” Mr Rotich said. “He is the first pupil from Kaptarkok Primary School to have a PhD. He is a role model now.”

Mr Rotich is one of the many people that Mr Kimaiyo brought to Nairobi for have a celebratory dinner after his graduation.

Mr Kimaiyo’s PhD project looked at China’s public diplomacy and how it has affected its image in Africa.

“When he joined, he was a very active student and was able to complete his coursework on time and we allocated him supervisors. I was one of his supervisors,” said Prof Maluki. “And he has walked the journey very bravely.”

In Keiyo South, people are busy on their farms, which have become smaller due to subdivision as the population has grown. They're tending to their potatoes, maize, vegetables and other crops, as well as looking for pasture for their traditional breeds of cattle, which don't produce much milk.

Residents hope their MP and his big dreams of education and electricity will change the trajectory of the place associated with Kenya's "Total Man".

“The driving force is poverty and trying to change home and the stigma we were facing,” Mr Kimaiyo said. He encourages those who make it to keep in touch with their home areas.

Of his latest feat, he says: “I can now marry. I am now free to marry.”