Students take part in Worldskills Kenya National Competition at Dedan Kimathi University of Technology in Nyeri County on August 31, 2023.

Darwin Mbogo, a 20-year-old student, was ecstatic to be among the thousands of 2023 Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education (KCSE) examination 2023 candidates selected by the Kenya Universities and Colleges Central Placement Service (KUCCPS) to pursue studies at a Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institution.

After completing Form Four at Grassland School in Nyahururu, Mbogo knew precisely what academic path he wanted to take, regardless of the grade he attained.

“I had a mean grade of C in the national examination. All I wanted was to join a TVET institution and pursue my dream training. My dream was realised when KUCCPS placed me at Kiambu Institute of Science and Technology,” Mbogo says, adding that TVET was the safer option due to the lower fees compared to university.

“My parents will pay Sh36,000 for the first semester, excluding accommodation, whereas a university would demand at least Sh70,000,” he says.

“I would have applied to a private university, but it would be a bigger burden to my parents. TVET is more affordable. I’m going to study cyber security and app development.”

The tech-savvy Gen Z adds that unlike universities, TVET institutes sharpen one’s practical skills.

“During my high school days, there was a lot of talk about certificate holders hiring people with university degrees, including doctorates,” Mbogo says.

His keenness towards TVET was also fuelled by the time it take to complete compared to conventional academic programmes.

“Courses take one to three years. There is no competition for space in TVET colleges unlike universities where almost everyone wants to be,” he adds.

A university degree has been seen as the pinnacle of academic achievement and a sure path to success for eons.

In recent years, however, a growing number of students has been going against the grain, choosing to forgo traditional university courses in favour of technical programmes – even when they score highly in KCSE examinations.

University education

As the cost of university education continues to soar and the job market becomes increasingly competitive, the appeal of technical colleges as a cost-effective and career-focused alternative is undeniable.

This shift in priorities raises thought-provoking questions about the value society places on different forms of education and the changing perceptions of what constitutes a successful career path.

Omondi Ngota, a former lecturer at Kabete National Polytechnic, has witnessed the shift in perceptions towards TVET, as graduates demonstrated their success in the job market.

He says when TVETs started as Technical Training Institutes (TTIs), student numbers were extremely low.

“There was a belief that anyone who went to those colleges was an academic failure. They have been proved wrong with time, especially when Kenyans began seeing the graduates make it in life,” Ngota says.

Society long equated university education with prestige and upward mobility. Once viewed as a fall-back alternative for those who could not make the cut for university, TVET institutes now attract students who seek hands-on training, industry-relevant skills and accelerated career paths.

From automotive repair colleges to the state-of-the-art kitchens of culinary schools, a new breed of students is embracing the practical, vocational approach to education.

Ngota highlights the growing recognition of TVET qualifications, even among university graduates.

“At Kabete National Polytechnic where I was, there were students who had university degrees. They came for diplomas, with the trend growing with time,” he says.

When it comes to hiring trainers, there is preference for those with practical experience over mere academic papers.

“When a TVET institute declares vacancies for trainers, it will seek people with master’s degrees, but when it comes to selection, the interviewing panel will be more interested in the individual who has a diploma in that course,” he says.

According to Ngota, TVET learners are ready for self-employment, as the hands-on training equips them with the necessary skills to perform their craft independently.

“The trainees are prepared to do their own work and not wait to be hired,” he adds.

For some fields, Ngota urges combining a diploma with a degree for a well-rounded skillset.

“If I have enrolled for a course in electrical engineering, I would preferably do a diploma, then proceed for a degree programme. It needs to be noted that papers are critical too, especially for management roles. It is good to combine the two for some courses. One gets a better chance in the work world,” he says.

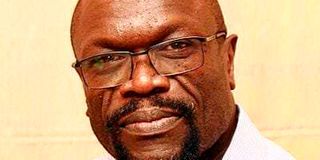

Omondi Ngota, former lecturer at Kabete National Polytechnic.

Ngota provides an interesting perspective on the shift towards TVET, attributing it partly to the proliferation of forged university certificates.

“When local universities started offering parallel programmes, their papers became suspect,” he says.

The “River Road degrees” phenomenon made it challenging to verify the authenticity of certificates.

“It became almost impossible to tell if people really had the degrees they claimed to have acquired,” Ngota explains.

The TVET certificates were hard to forge as they were issued by the Kenya National Examinations Council.

“It is at this point that TVET certificates started gaining respect,” he says.

Ngota also touches on the practical value of education.

“The element of having a degree started waning when people realised that you can actually have the paper but still fail to put food on the table,” he says.

Employers, he says, prioritise practical skills over academic credentials when hiring for technical roles.

TVET students’ motivations are as diverse as the fields they pursue. Some are driven by a desire for financial independence at the start to their careers, while others are drawn by the promise of ready skills that align with the demands of today’s rapidly-evolving job market.

Defying conventional expectations, Mary Abisai, who scored a mean grade of B in the KCSE examination at a national school in Nairobi, has made the decision to pursue her passion for culinary arts at a TVET institute.

Abisai will soon join Kenya Utalii College, renowned for its culinary courses.

“I know it has come as a shock to many that a B student would join a TVET institution. I have gone for skills instead,” she says.

The condensed short duration of TVET education appealed to Abisai’s desire for expediency, enabling her to bypass the extended commitment required for a degree.

“Why would I go to a university for four or more years when I can develop my skills at a TVET for just two?” she asks.

Forgoing the traditional university path in favour of TVET was deliberate for Abisai. Her dream is to be a chef. Since childhood, Abisai was fascinated with the kitchen.

Despite her parent’s efforts to convince Abisai to pursue Medicine, she remained steadfast in her aspirations. The decision to take the TVET route was driven by an understanding of the time and resources needed to get the skills she craved for.

“She has dreamed of being a chef from a very young age,” her mother told Higher Education.

So, what could be driving this educational renaissance? Ngota says TVET diploma courses are designed to equip students with practical, hands-on skills.

“The small class sizes in TVET colleges have enabled more focused practical training compared to universities. Diploma institutions usually have about 30 students per class as opposed to universities that can have as many as 300. Practical lessons are not given much attention at university,” Ngota says.

According to the 2024 placement report released by KUCCPS two weeks ago, a total of 75,718 applicants secured places in TVET institutes, including 11,991 who qualified for degree programmes.

Education Cabinet Secretary, Ezekiel Machogu, said the cumulative approved capacities in selected institutions were 1,078,806, with 278,006 in universities (degree), 769,820 in TVET colleges and institutes, 13,808 in teacher training colleges and 17,172 in the Kenya Medical Training College (KMTC).

As Kenya marks a Century of TVET this year, experts attribute the growth of its popularity among young people to the abundant opportunities offered.

According to Erick Katana, the principal of Bandari Maritime College in Mombasa, the preference for TVET is rooted in the emphasis of the institutions on practical, skills-based training, which aligns with employers’ demands.

“TVET courses are more skills-based than theory-based. This is what companies all over the world are looking for,” Dr Katana says.

TVET Authority Director-General Kipkirui Langat, echoes the sentiments, highlighting the investments by the government in revamping these institutions as a driving force behind the surge in interest.

During a public lecture at Bandari Maritime Academy in Mombasa on May 21, Dr Langat stressed the important role TVET institutions will play in revolutionising higher education in Kenya.

“The government is promoting critical skills that had been neglected for long, providing huge opportunities for young people in areas like welding, maritime, agriculture and construction,” he stated.

“We want to show young people the areas with opportunities in TVET. We are providing access to training.”

Kenya’s commitment to exporting a skilled workforce has encouraged young adults to pursue TVET courses.

The country has signed bilateral labour agreements with several nations, offering employment prospects that entice young people, according to Dr Langat.

Michael Vallez, the founder and Director of GFP International – who delivered the key lecture at Bandari College – urged students to embrace vocational training “because it offers job opportunities”.

“Vocational colleges are very important. Take up courses in TVET colleges and employers will come looking for you. The Kenyan government must upgrade its TVET institutions with modern machines and trainers,” Vallez, who is an engineer, said.

At the same event, the Education Cabinet Secretary said the government has prioritised modernising and repositioning TVET institutions to align with labour market demands, economies, and needs of society.

“The goal is to promote skills development for empowerment, productive employment and decent work. We want to facilitate the transition to more digital, green and inclusive economies and societies in line with the 2022-29 Unesco strategy for TVET,” the minister said.

He highlighted the historic significance of TVET in Kenya, tracing its roots to the colonial times when industrial education was introduced to train Africans in practical and technical skills.

According to Patrick Muchemi, the principal of Kabete National Polytechnic – the oldest TVET institution in the country – this shift is driven by campaigns promoting skills acquisition and the job prospects offered by vocational training.

“On top of that, the trainees are learning from students who have completed university education, some with advanced degrees, but who remain jobless. There are thousands of university degree holders who have not secured meaningful employment for years,” the principal says.

Kabete National Polytechnic has admitted many 2023 KCSE examination candidates, some having scored high grades but chose the institution instead.

Muchemi, an expert in construction, says courses in construction, engineering, electrical engineering and hospitality are among the most sought-after by students who complete KCSE tests.

Notably, many female students are showing interest in traditionally male-dominated courses, indicating a shift in perceptions by the society.

According to Muchemi, some students opt for TVET after failing to secure university admission due to cluster subject requirements.

“They think of starting from a lower level – diploma. There is also a notion among company executives that those who start from the bottom make good employees when it comes to skills acquisition,” he says.

Political leaders have also played a role in promoting vocational training, highlighting the demand for skilled tradespeople like plumbers, welders, hairdressers, construction workers and mechanics.

Stanley Muindi, the Director of Technical Services at the Kenya National Qualifications Authority, says many students are opting for TVET due to the emphasis by employers on skills acquisition.

Employability

“Education is viewed for employability and not just for grades, performance, labels or certificate purposes. If education is key to getting employed, mobility and lifelong learning, then TVET is the master key,” Muindi says.

He cites the Unesco strategy for TVET and the 2016-30 Kenya National TVET Blueprint, which identify vocational education as the greatest enabler of employment.

“The moment you have a technical and vocational skill, you stand a higher chance of getting hired,” he says.

The expert adds that employers are seeking competent workers who can perform specific tasks, rather than focusing solely on academic degrees.

“Employers are interested in people who have competency, not certificates, diplomas, bachelors, masters or doctorate degrees. They want a competent worker who can perform the task given effectively,” he says.

As labour markets, economies and societal needs rapidly evolve, emphasis is quickly shifting to competence.

Says Muindi: “If you have a skill in tilling or are an expert in doing ceiling boards, you will be hired based on the competencies you possess, not the diploma or degree. These skills are found in TVET colleges. It should be noted that young people no longer want to spend an eternity at an institution of higher learning and even more looking for a job.”

Instead of pursuing five-year engineering degrees, Muindi notes that many individuals now prefer shorter courses that lead to employment opportunities.

While the allure of TVET continues to grow, some students still insist on pursuing university degrees.

John Nyabuti, 23, who sat his KCSE examination at Nyakeore Secondary School in 2023 and scored a B-(minus), is delighted after being placed at Kabianga University to study Agriculture Extension and Education.

“I have always dreamt of acquiring a university degree,” says Nyabuti who expects to join the Kericho-based institution in August.

“I know TVET programmes sound better but a degree is what I want. I will be an extension officer and an educationist on completing the four-year course.”

Similarly, Victor Lemashon, 18, who completed his secondary education at Cheptenye Boys High School was elated on learning that he had been placed at the University of Nairobi for a Bachelor of Arts in Theatre Arts and Film Technology course.

Societal pressure

Lemashon scored a B plain in the KCSE examination. The teenager acknowledges the appeal of TVETs.

“My first option was Software Engineering at Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture Technology. I know many peers are opting for TVET because of the time it takes to complete the programmes. The high university fee, frequent strikes by students and lecturers and other social issues are the other determining factors for joining these institutes,” he says.

According to Lemashon, societal pressure and parental expectations often influence one’s decisions to pursue university education. He urges parents to stop putting pressure on their children to pursue particular courses.

Mr Machogu acknowledges the contribution of educators, trainers, professionals and partners who have been the backbone of TVET courses in Kenya.

“From cutting-edge technology and engineering solutions to advancements in healthcare and sustainable development, our TVET graduates have made significant contributions in many fields,” the minister says.

“We will host exhibitions, demonstrations and competitions to highlight these accomplishments and inspire a new wave of talent and creativity to mark 100 years of TVET in Kenya.”

The Cabinet Secretary emphasises the need to strengthen partnerships, linkages and collaborations between TVET institutions, the private sector, employers and development partners to ensure the programmes continue to evolve and meet the demands of a rapidly changing world.

With the objective of mitigating challenges like low perception and access to TVET, the centennial celebrations, according to Machogu, will seek to inspire hope among citizens and ignite interest in the potential of TVET colleges to spur employment, inclusivity, equity, entrepreneurship, lifelong learning and decent livelihoods.