How devolution has powered women to political leadership

The seven women governors. Top from left: Cecily Mbarire (Embu), Fatuma Achani (Kwale) and Gladys Wanga (Homa Bay). Bottom from left: Wavinya Ndeti (Machakos), Susan Kihika (Nakuru), Anne Waiguru (Kirinyaga) and Kawira Mwangaza (Meru).

What you need to know:

- Kenya has yet to achieve the two-thirds gender principle in key leadership cadres, but more women now hold key political offices that influence decision-making at both national and county levels.

- The creation of the 47 counties marked the beginning of new positions, including women representatives, senators, governors, deputy governors and members of the county assembly.

Touted as one of the most progressive supreme laws in the world, the 2010 Constitution brought with it great promise and expectations for Kenyans.

Women were among the major winners, as it, in particular, laid the foundation for their increased participation in leadership through the creation of 47 counties.

The Constitution further introduced the two-thirds gender rule, which, though not yet actualised, provides for gender equity in elective and appointive leadership. It says no gender should occupy more than two-thirds of such positions.

Besides, the introduction of devolution was further meant to end discrimination and gender inequalities by promoting inclusion in the county leadership. Has it helped achieve this goal?

First implemented after the March 2013 General Election, devolution has increased women’s representation in the counties through several affirmative action initiatives such as leadership quotas in the assemblies and executive committees.

The assemblies have been applying the two-thirds gender principle through nominated seats. The Kiambu assembly, for example, has 86 members, 26 of whom are nominated: 24 women and two men.

Pacifica Ongecha is a beneficiary, having been nominated to the Kiambu assembly after the last general election. She notes that devolution has amplified the involvement of women in political leadership.

“Women have been elected as governors, senators and MCAs. The women MCAs have, in particular, been instrumental in championing issues that are sensitive and beneficial to women. We have a right to vote on all matters brought to the assembly, some of which touch on women and girls,” Ms Ongecha, a gender activist, tells Nation.Africa.

She, however, adds that those nominated should always strive to get elected in subsequent elections. “Women nominated MCAs and MPs should take these positions as a platform to venture into elective politics. Through devolution, we have made some progress, but we are not yet where we want to be.”

However, Ms Eunice Karoki, who served as Kiambu County executive during the William Kabogo administration, disagrees with Ms Ongecha, saying the impact of the nominated MCAs, most of whom were women, was not felt on the ground at the time.

“The nominated MCAs were not proactive at all. We, in the executive, never felt them. They lacked the voting rights on key critical matters touching on residents, including women. They had a big title but were powerless,” Ms Karoki tells Nation.Africa in an interview.

The former county official also faults the criteria normally used to pick the nominated MCAs, saying it could be the reason for their poor performance.

“Many of the nominated MCAs could not have been picked through merit. Some even did not even seem to know what their work entailed. I think there is a need to review the criteria used to pick the nominated MCAs so that we can have only those who only merit in order to maximise their performance,” she says.

Kenya got a historic number of female governors in the last general election. They are Susan Kihika (Nakuru), Gladys Wanga (Homa Bay), Cecily Mbarire (Embu), Wavinya Ndeti (Machakos), and Fatuma Achani (Kwale), Kawira Mwangaza (Meru) and Anne Waiguru (Kirinyaga).

The number of female deputy governors has also been rising since 2013, when seven were elected. The number rose to nine in 2017. Last year, eight female deputy governors were elected. A total of 115 women were also elected as MCAs.

Fridah Githuku, the executive director at Groots Kenya, describes devolution as a political academy for women leadership. This, she says, is evidenced by the gradual increase in the number of women elected as senators, governors, MPs and MCAs in the last three general elections and the transition by some women senators and reps to governors, MCAs to MPs and county executives to legislators.

“The proximity of the devolved system to the grassroots, where the majority of the Kenyan women are, also means devolution is reducing the long distance to power that had persisted since Independence and locked women out,” she tells Nation.Africa.

Besides enhancing involvement of women in political leadership, devolution has also resulted in more women assuming senior county positions. Between 2013 and 2017, they, for example, constituted 24 per cent of CEC members and 34 per cent in county assemblies countrywide.

Women reps

The 2010 Constitution also created 47 women representative positions as an affirmative action to increase the participation of women in political decisions, and build the profile of women in the national arena.

Additional nomination positions in the National Assembly and the Senate have been set aside for women primarily to boost their numbers and compensate for their historical marginalisation. However, despite some progress, there remain many barriers to the full political participation of marginalised groups in Kenya.

The gender rule dilemma stalked the 10th, 11th and 12th parliaments, with their four attempts to operationalise the rule failing to find a solution. The Constitution required Parliament to enact legislation to achieve this quota within five years, but numerous attempts have failed.

Last year, the number of women elected still fell below the constitutional threshold as only 30 women were elected to Parliament, representing 8.6 per cent women representation in Parliament. This is attributed to not just absence of a legislative framework but also cultural, financial, and political barriers and violence that still threaten women’s participation in the political space.

According to the analysis of the August 9, 2022 election done by the National Gender and Equality Commission (NGEC), out of the 290 constituencies, at least 29 women MPs were elected. This is a 30 per cent increase in the number of women elected from the single constituency as MPs in 2017 when only 23 were elected. This means even with the 47 women representative seats and nomination slots set aside for women, the National Assembly, which has 349 MPs, has only 80 women.

In the Senate, only three women were elected. This means the Senate – with 67 senators, including the nominated ones – only has 21 women senators.

Regional comparison

Despite the significant increase in the number of women elected, the two thirds gender principle has yet to be adhered to. Kenya is trailing in the East African Community, with its women’s political representation accounting for 21.4 per cent of Parliament.

According to a Perline monthly report, the Rwandan election of 2018 had 49 out of 80 seats in the Lower House going to women, representing 61.3 per cent. In Ethiopia’s 2021 elections, out of 470 seats, 195 seats went to women, representing 41.5 per cent. In Uganda, during the 2021 election, women garnered 188 out of 556 seats, representing 33.8 per cent.

To jumpstart the implementation of the gender rule, President William Ruto in December last year wrote a memorandum to the speakers of the National Assembly and the Senate in which he outlined the need to implement the constitutional requirement. “It is regrettable that implementation has become a conundrum. There is a profound sense that we have failed Kenya’s women and I believe it is time to make a decisive breakthrough,” he wrote.

Dr Ruto proposed a top-up of 40 more women in the National Assembly and the Senate as is the case in the county assemblies. The maximum number required to meet the two-thirds threshold is 26 in the National Assembly and 14 in the Senate. He registered his commitment to avoiding the Executive being plunged into a stalemate with the Judiciary as witnessed under his predecessor, Mr Uhuru Kenyatta.

Gender taskforce

Last month, Public Service and Gender Cabinet Secretary Aisha Jumwa inaugurated the Multi-Agency Working Group on gender rule, made up of both state and non-state actors. It is aimed at overseeing an inclusive process. Ms Jumwa expressed optimism that the dream of achieving gender rule will finally be achieved.

“There have been several attempts to implement the two-thirds gender rule from the MPs and the Executive, all of which have failed. We have now embarked on a new journey that has the support of the highest office in the land,” she said.

The CS noted that the process would begin with building consensus among stakeholders. Speaking last week when she opened this year’s Women Rights Convention organised by the Community Advocacy and Awareness Trust (Crawn-Trust), she said the team will collect views during public participation forums across the country.

She noted gender rule being part of the bipartisan talks as a sign of goodwill from the government and the opposition. “In the past, we have suffered from lack of political goodwill, but now we have it. We need the gender rule to be realised. We now have an opportunity to realise it. Each one of us has a role to play.”

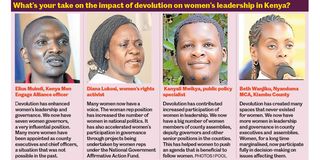

Vox pop

Daisy Amdany, the executive director at Crawn-Trust and the co-chair of the multi-agency group, says collaborations with government and other stakeholders will be key to achieving the constitutional requirement. She has commended the CS for taking a bold step in setting up the taskforce, adding it is now time to “stop doing theory and move to action”.

“We will need collaborations and work with the government to address the concerns of women. Until the gender rule is implemented, our democracy is at stake. It is our hope that we will celebrate at the end,” Ms Amdany says, advising women leaders and rights organisations to unite and work together to realise the principle. “We are stronger together. We need to pay a price. Doing nothing is costly.”

Jackie Mbogo, the chief of party at Re-Invent Kenya, has also challenged women to speak loudly about the two thirds gender rule. “The implementation of the gender rule is not negotiable. It is ours. It is our constitutional right and let us not speak in low tones about it,” she said.