How rape culture led Tarana Burke to launch Me Too movement

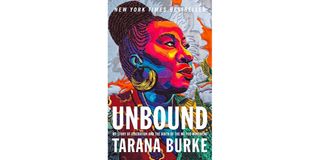

The cover of Tarana Burke's memoir, Unbowed: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement.

What you need to know:

- Tarana grew up in the Bronx, the fourth largest of New York City's boroughs and the most impoverished of its five locales.

- Just after she turned seven, while playing outside, a boy older than her took her by the hand, walked her to a dark secluded corner in a partially abandoned apartment and defiled her.

Tarana Burke's conscientious work spans three decades of labouring with effusiveness for communal healing and justice for victims of sexual violence.

She has received numerous accolades, including Time Person of the Year in 2017, Time 100 Most Influential People in 2018, Sydney Peace Prize in 2019 and USA Today Woman of the Decade in 2020.

Tarana grew up in the Bronx, the fourth largest of New York City's boroughs and the most impoverished of its five locales. Just after she turned seven, while playing outside, an older sadistic boy in her close-knit Bronxdale neighbourhood took her by the hand. He walked her to a dark secluded corner in a partially abandoned apartment and defiled her.

She was defiled again at nine by another boy eight years her senior at Sacred Heart Primary School. Before she became a grown-up, Tarana did not understand what rape was, hence could not relate it to her recollections. Words like rape, molestation, and abuse were foreign to her.

They had no definitions, no context, even though she was often informed by her mother to prevent boys from touching her private parts.

Therefore, when she thought of her defilement, she didn’t hold her abusers liable and instead blamed herself. To her, they didn’t abuse her; she had rather broken her mother's rules and committed an offence. It was this naivety that gave her thoughts a uniform sense of disillusionment and prevented her from identifying as a survivor.

Also read: We must fight rape culture in Kenya

Most victims are brainwashed and psychologically manipulated by perpetrators and communities to believe they have been complicit in their own abuse. Therefore, they don't speak out because of the intense shame and fear of being ostracised, as society bashes women who speak out, prompting many victims to stay silent.

It was only after Tarana read one of her mum's books, I know why the caged bird sings by Maya Angelou, that it dawned on her that she had been defiled.

Maya wrote of being molested by her mother’s paedophile boyfriend, Mr Freeman, when she was eight. Until then, Tarana's mind had not understood that defilement was perpetrated on innocent girls. It altered her mind and she no longer felt alone.

Tarana's memoir, Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the birth of the Me Too Movement, discusses broadly how black women are at disproportionate risk of rape. Sixty per cent of black women report being subjected to coercive sexual contact by age 18.

As a teenager, Tarana joined a civil rights organisation called 21st Century Youth Leadership. It funded her scholarship in 1996 as a 22-year-old to Alabama State University in the southern city of Selma.

She began travelling throughout the US with the 21st Century Movement and spoke whenever people authorised her space. She articulated her Me Too idea and how the exchange of empathy between survivors of sexual violence could be a tool to empower women towards healing and into action.

Me Too's purpose was to inform survivors that they are not alone. It was to let women, particularly young women of colour, know that they had a voice. It was beyond a hashtag and was the beginning of a larger conversation and a movement for radical communal healing.

Self-worth

She turned her focus to building a sense of self-worth in black girls. What she saw missing in several girls was a connection to how valuable their lives, current and future, were.

Therefore, Tarana focused on boosting their self-worth by providing them with mental tools to counteract the messages of worthlessness the world was instilling in them.

She wanted them to know their history, to think profoundly about the contributions they wanted to make in their communities, and to figure out how to achieve that.

She also wanted them to feel seen, heard and valued. Many of her sessions took place in local schools twice a week. The girls engaged in plenty of oral communication.

It took a while to get them used to talking after previously being bashed that they were too loud, too nosey, too talkative, or just too much. Once they opened up, their reveals became fluid.

Some of Tarana’s participants included two middle school girls who were gang-raped, one of whom tried to commit suicide as a result. Another of the gang-raped victims became pregnant at 14 and was made to keep the baby as punishment by her relatives.

Another girl was in the local foster care programme with a baby she’d had by her mom’s boyfriend and was pregnant with a child of another sexual abuser.

When her daughter, Kaia, was nine, Tarana candidly asked her to confide in her if anything sexually unusual ever happened to her in the past. Kaia wrote down how she had been sexually abused by a boy during a school gateway.

The continual perplexing heartbreak propelled Tarana to valiantly establish and champion Me Too globally.

The reviewer is a novelist, a Big Brother Africa 2 Kenyan representative and the founder of Jeff's Fitness Centre (@jeffbigbrother).