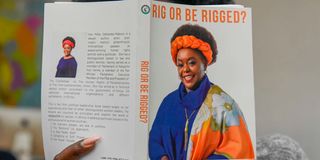

The making of a firebrand: Millie Odhiambo's 'Rig or be Rigged' tell-all

From left: Narc-Kenya leaders Martha Karua, author Millie Odhiambo Mabona and Homa Bay Senator Moses Kajwang’ during the launch of her book in Nairobi on October 1, 2024.

What you need to know:

- Millie Odhiambo, self-described as "painfully shy" in her youth, evolved into one of Kenya's most vocal and longest-serving female politicians.

- Her political journey began unexpectedly when, at 13, she secretly witnessed the vote counting for a pioneering woman candidate she admired.

- Falsely rumoured to be dating high-profile politicians, she initially leveraged these misconceptions to open doors, but now advises women in politics to rise on their own terms and avoid the "bottoms-up" approach to gaining power.

In her own words, Millie Odhiambo was born “a painfully shy” person. Through a mix of factors; identifying and seizing moments, paying attention to inner voice and counting on Providence, she has scaled the political ladder to become the current Parliament’s oldest serving (Member of Parliament) MP, and now a Minority Whip.

Imagine a 13- year-old girl in Homa Bay sneaking into a regional tallying centre, enduring all the perils of the dark, waiting on the tallying votes of a pioneer woman candidate she looks up to?

The year is 1979 and by then, only five women have been elected in Parliament since independence. In the hall where ballots for all constituencies in the region have been brought, she’s ensconced among multitudes of sweaty constituents, yawning, scratching and waiting to witness history being made.

At the turn of the clock midnight, and after a painstaking wait, it’s the turn of Karachuonyo Constituency votes to be tallied, and the young girl juts out her neck, eyes wide open, as one vote after another is counted, and placed at the candidates side.

At the close of the exercise, Phoebe Asiyo has floored the Kanu giant of the time Okiki Amayo who cries aloud, protests and demands a recount, pushing the exercise longer to dawn. As the sun rises, flashing her golden rays on the surface of Lake Victoria beneath, Asiyo is declared the MP-elect, and the elated young girl hops in jubilation to her home after recording history, with her eyes.

That is how “woke” Millie Odhiambo-Mabona was in her childhood, as can be gleaned from her recently launched book, “Rig or be Rigged?” It is a tale of grit, focus, relentless spirit to reclaim an original family dream and legacy.

For a girl whose doting father Harrison Odhiambo died two days after her seventh birthday in a boating accident while campaigning for the Karanchuonyo parliamentary seat, politics was ingrained in her at an early age. He had been a member of the former Regional Assembly for Nyanza, and the Chief Executive for Kanu in Nyanza.

At that age, the platonic relationship between a girl and her father is beginning to forge, and the thought of being suddenly separated for good, is as tragic as death itself. She not only lost a father, but also lost all the privileges that came with being around a powerful local figure.

“I had my initial glimpse of politics in the short time I knew him. I remember our house was always full of people who slept in every available space, including the veranda,” she says in the book.

Politics was an intrusive, extravagant and people-pleasing affair. But there was also awe, honour and service in it, making her somewhat confused as to whether to place it in her focus of life pursuits.

Throughout high school, university, initial stint as a civil servant working at the Attorney General Chambers, and later in civil society, Millie never fancied politics. The turning point, however, was in the year 2005 when a mix of factors placed her in the line of active politics.

Seizing the moment

She’d been an active member of the National Constitutional Conference in Bomas when it acrimoniously wound up, leading to a patch-up process which resulted in the now famous Wako Draft Constitution, named after former Attorney General Amos Wako, who took a raw draft to Kilifi and worked on it by himself before it was presented to the people for a national referendum.

These were confusing times. For close to a decade and a half, people had been fighting for a new constitution and now it was close to being delivered, but a heavy cloud of doubt as to whether this was it, hung loose in the Kenyan troposphere.

Millie was invited, through Prof Jacqueline Oduor, to pitch for the orange (No) side of the referendum in a television debate against the banana’s (Yes). She was initially reluctant on account of the short notice, but also because of the heavy political undertones the process was gathering.

In the end and after balancing the scales, she opted to participate and there and then, her political trajectory as an “Orange” luminary began in earnest, with the media shining a spotlight on her prowess.

“My presentation resonated very well with viewers and the media as demonstrated by the attention I received at the end of the debate. I noted the new-found look of admiration from members of the fourth estate,” she writes in the book.

From then on, she was invited to countless other debates, meetings and interviews, including one where she was paired with the country’s legal heavyweights of the late Mutula Kilonzo who was also her former teacher, the late Mirugi Kariuki, and prominent woman leader Beth Mugo.

“For the first time in my life, the media used the word leader to refer to me after the show,” she says.

Exit the orange versus banana campaigns, and the oranges converted themselves into Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) party, and Millie retreated to her activism. When the new party was undertaking grassroots elections, she stepped in to help his relative, the late Otieno Kajwang’, where she came face to face with intrigues and realities of political life.

Young, petite, and politically naïve, she was at one time ordered out of her own vehicle and told the owner had instructed that it be used by the party leader, Raila Odinga: “I did not look like I could own the car,” Millie says of the incident, which involved former Raila aide Silas Jakakimba.

Innovate, elevate… do not settle

After party primaries, she came up with the idea of a Western Kenya Presidential Campaign team, to repair the damage wrought on the party by divisive primaries. Luckily, the idea was endorsed by the rank and file of the party, including Raila.

In the book, Millie says they campaigned in more than 50 constituencies and of those, only two seats were lost to other parties. The presidential election of 2007 turned chaotic, and post-election violence rocked the country.

The party had, however, earned itself six nomination slots for Members of Parliament, and Millie was picked to be one of them. When the country picked itself up from the ghost of violence, it embarked on comprehensive reforms for which Millie would play a critical role, cementing her place in the political space she had carved for herself.

As a member of Parliament’s Justice and Legal Affairs Committee, every consequential legal reform executed between 2008 and 2013, including the formation of the Parliamentary Select Committee (PSC) on Constitution, passed through her hands.

She was also appointed to be among the group of 27 PSC MPs who negotiated the final draft in Naivasha. It is in here that she developed what she calls a “constitutional scar” usually covered by her trademark wig.

A little wound on her head courtesy of a bad chemical she had used while visiting a salon in Rwanda, had spread all over her head. And because of the wig she was wearing to cover it, coupled with the heat of Naivasha at the time, the head started producing pus.

“I lost all my hair after Naivasha,” she reveals in the book, saying the stakes were so high there that members even dreaded visiting washrooms so as not to lose out. She later sought specialised medical attention, but still wears a bald of honour to this date.

You would think after such a starling performance nationally, she would have it easy in her constituency the moment she decided to vie.

Tossing self in the fray

In the run up to her declaration to run for Mbita Constituency seat, everything that could go wrong started going wrong. First, her mentor and incumbent MP Kajwang’ threw his weight behind her cousin, despite convincing her to run for the seat.

On August 12, 2011 the day she was to officially declare her candidature, her mother - the only parent she had left, died.

Apparently, opponents had descended on her with all manner of slurs, including on the basis of her not having a biological child. Two days before she passed on, her mother called Millie’s sister in panic, fearing her child may be harmed in the campaigns.

“It was not lost on her that my dad had died in an accident several years earlier while vying for the same seat. I think she had a panic attack or a feeling of de javu of sorts that made her panic,” she writes.

Her grandmother similarly collapsed in shock, and died a day after her daughter’s burial. A young relative was involved in an accident on his way to Millie’s mother's funeral, was in an ICU for a month, and died too.

Rig or be rigged?” book by Millie Odhiambo Mabona pictured on October 15, 2024 at Nation Centre in Nairobi.

Her mother’s cousin who was at the funeral collapsed and died, and yet another of their cousin died in a road accident shortly thereafter. Devastated, Millie picked herself up from the misfortunes and trudged on.

She says she had to learn to freeze her grief, suspend the mourning, campaign and get over the concurrent betrayals, all at once.

After a whole year of positioning self, and campaigning, the actual party primaries were held on February 17, 2013. It was a baptism of fire for Millie as she came face to face with blatant rigging attempts in every manner of it.

When she, together with her team, stumbled on opponents marking fake ballots, they confiscated them and tore them apart, earning herself the reputation of a tough defender of her vote.

“The party was later informed that I was very violent, tore all the papers and urinated on them. In hindsight, I wish I had – you know, urinated on them,” she writes.

After pulling all stops to win the primaries, she realised there was one more battle she had to fight; getting the party certificate. For this, she had to crisscross Western all the way to Eastern, in Machakos where the party leader was holding a rally.

“I was informed by the party leader that he had been told that I had lost the primaries, that I had been violent and even urinated on the ballot papers,” she adds.

Later, after establishing the truth, Raila ordered she be issued with the certificate and the rest is history. She became the only woman elected in a single-member constituency through ODM in the whole country.

Invaluable lessons

In the book, Millie uses her experience to pass on lessons on access and maintenance of political power. In it, she offers invaluable lessons to upcoming women leaders including deployment of soft-power, identifying and dismantling rigging schemes, identification of “real owners of the party” and how to work around them, and how to engage with the media.

She says for better prospects at political leadership, aspirants must uphold human values, connect with the people at their level, embrace challenges as a springboard to greater things, be decisive and for women, avoid sounding like a whiner or griper.

One must step out there, dress to express self, know when to hold the tongue, and remember that all politics is local. The lessons are interspersed with personal anecdotes to drive the points home.

“Even though I am a practicing Christian and teetotaller, I have been a life member number three at the Parliament bar. In politics, long range planning is rare and weak. Decisions are sometimes made instantaneously at bars,” she says.

She advises aspirants to mind spouses of political figures as they have “residues of power that they can use against you.” She tells women politicians to be kind and fair to each other, and to avoid “pull her down syndrome” or PhD as she calls it.

Read also: What politics has taught us

She cautions women politicians against “bottoms-up” approach to accessing political power, recounting her own experiences. She confesses that one time a “super-rich male colleague” in Parliament tried to hit on her, telling her that she needed a socio-political financier to survive the game.

When she shared this with a woman colleague, she endorsed the man’s idea, asking her not to be mean with herself: “You need money for campaigns, give him, in any case, exchange is a fair game.”

She says although some women politicians sleep their way to Parliament, the best situation is where one rises up on their own terms, without having to become a hostage of carnal longings of a man. She says because of this few, women who earn it by their own stripe are disbelieved.

In the book, she says when she was nominated, she was initially assigned- through public gossip - to current President William Ruto who was a member of Pentagon, later Raila, and much later retired President Uhuru Kenyatta, for boyfriends.

“I was offended when I heard it, then a senior female colleague told me to use it as leverage. I, therefore, got cheekily quiet. I let people believe it. It opened doors,” she writes.

She also offers practical lessons to beginners, among them investing in planning, identifying a constituency, understanding the nature of the battle ahead, community mapping, constituting a core team for strategy, mobilising resources, popularising oneself and being culturally-sensitive.

She talks about the power of marketing and branding in politics: “I used to greet people using my Suba greeting; Geza Geza. The name became my identity and preceded me. It sold me more than my regular name Millie Odhiambo-Mabona.”

The book’s launch was supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.