Premium

How Jomo Kenyatta govt failed to resolve colonial land question

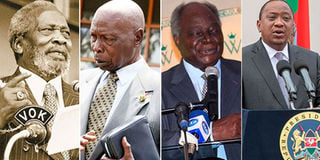

Kenya's presidents since independence, from left: Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, Daniel Arap Moi, Mwai Kibaki and Uhuru Kenyatta. As the country gears towards its 13th General Election, there seems to be no cure in sight despite political promises to resolve the land problem, one of the most contested issues in independent Kenya.

After 70 years of British rule in 1963, the new Jomo Kenyatta government was left with one headache: Land. Some 59 years later, and as the country gears towards its 13th General Election, there seems to be no cure in sight despite political promises to resolve one of the most contested issues in independent Kenya.

While the regimes of Jomo Kenyatta, Daniel arap Moi, Mwai Kibaki and Uhuru Kenyatta attempted to find solutions to the nagging problem, albeit with limited success, the leading presidential contenders for the August 9 election – Orange Democratic Movement leader Raila Odinga and Deputy President William Ruto – are making similar promises.

Land grievances and rights, more than anything else, informed Kenya’s struggle for independence as poverty and squatter problems started to cause tension after the British policy to create what Dane Kennedy – a professor of history at George Washington University – calls “Islands of White” backfired.

Before independence, White settlers occupied an equivalent of three million hectares, half of which was suitable for cash crop growing while the remaining was suited for large scale livestock production. An estimated 3,600 White settler families, constituting only one per cent of the population, occupied about 20 per cent of Kenya’s arable land while six million Africans were pushed to the so-called Native Reserves and “tribal lands”.

Uprooted from ancestral lands

The alienation of the best land reserves for White settlers uprooted families from their ancestral lands and altered the country’s demography.

Later policies set in place to address the emerging problems complicated an already complex problem.

Eight years to independence, the 1955 East African Royal Commission – set up to review economic development in the three British colonies of Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika – recommended that the government policy should move towards advocating individualised freehold tenure and the creation of private property rights in “tribal” lands. This policy is still followed as a solution to the nagging land problem.

The thinking, then, was that the privatisation of property and the sanctity of a title deed would trigger an economic boom in the reserves – and that the switch to individual land ownership would silence the clamour for independence in what settlers thought was the “White man’s country”. Thus, a White settler’s title deed would, under the law, be equivalent to a title deed held by an indigenous Kenyan.

A year earlier in 1954, the Swynnerton Plan – named after colonial Permanent Secretary of Agriculture R.J. Swynnerton – had proposed the displacing of indigenous land tenure systems with private property rights along the lines of English land law and as a response to the Mau Mau rebellion. This consolidation and titling of land took place at the height of the state of emergency, triggered by the Mau Mau fighters’ violent demand for land rights.

New set of bitter squatters

While it was the first time the government agreed to individualise land ownership in rural areas where land was either communal or ancestral, the consolidation created a new set of bitter squatters after 1963 – the former freedom fighters.

It would also create the first cracks in the Kenyatta government as radicals like Vice-President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga continued to push for allocation of land to African victims of colonial expropriation.

The latter fell out with the President largely over the land question less than three years after independence to form the opposition Kenya People’s Union (KPU). He was joined in the KPU by Mzee Kenyatta’s jailhouse colleague from the “Kapenguria Six”– the freedom fighters whose arrest by the colonial regime in 1952 marked the beginning of the state of emergency – Bildad Kaggia.

The other freedom fighter to fall out with Jomo Kenyatta over land policies that simply replaced colonial masters with a new African elite was another member of the Kapenguria Six Fred Kubai.

Another was Kenyatta’s first private secretary at independence and later assistant minister Josiah Mwangi Kariuki – a populist MP who was assassinated in 1975.

Nagging question

In the first decade after independence, the fate of tens of thousands of central Kenya men and women who had been detained and dispossessed of land while away in camps, was to become the nagging question.

Similarly, the future of ancestral lands that had been converted to Crown land and given to settlers was becoming thorny. This was mainly so in the former provinces of Rift Valley, Central, Eastern, Western and Coast.

During the Lancaster talks on a new Kenyan constitution and in independent Kenya, the Land Order-in-Council of 1960 which introduced the “willing-buyer willing-seller” policy was adopted, mainly by British bureaucrats, to provide for the conversion of (native) leaseholds into freeholds and to govern the transfer of land in the White highlands.

Though controversial and not embraced by settlers – who wanted the government to compensate them and they walk away – and the African nationalists – who wanted the land free or Britain picks the bill – the policy would later inform land transfers in Kenya.

Willing-buyer willing-seller

Conservative elites in Kanu, led by James Gichuru and Tom Mboya, who had initially resisted the willing-buyer willing-seller policy, would later adopt it. However, it was opposed by some radicals and Mau Mau fighters, led by Gen Baimunge, who refused to lay down arms until it was settled. These fighters were hunted down by the Kenyatta government in Mt Kenya forest and killed.

By silencing radical voices, the Kenyatta regime embarked on land transfer financed with loans from the World Bank, Germany and Britain.

Beneficiaries were to pay back the loans with interest but as it emerged later, only the poor were repaying while the well-connected elites, who had also posed as landless, reneged. The unpaid bills were picked by taxpayers since Treasury had to pay.

Also, as the poor lined up for the settlement farms on offer, the African elites – mostly made up of colonial beneficiaries, politicos, civil servants and homeguards – managed to purchase land under the “willing-buyer willing-seller” framework thus sabotaging the overall programme.

This created a new middle class as the elites started to replace settlers in the highlands as earlier proposed under the failed Yeomen scheme.

New African middle class

The Yeomen scheme had been created during the state of emergency, and in a bid to create a new African middle class in the White highlands. The idea was to have different races live together in the highlands and silence calls for the region’s opening up.

That way, it was thought, the demand for the transfer of land would cease and settlers in the White highlands would not be targeted by nationalists. Under the Yeomen scheme financed by the World Bank, the few elite Africans were to get some 5,000 acres each and would farm alongside Whites.

While this plan collapsed, it would inspire the Z-Plot scheme which was mooted by the Kenyatta administration to allow elites take over choice farms. Under this programme, the elites allocated themselves colonial farm houses and 100 acres on the lands offered for settlement.

As the projects started, the initial question on whether White settlers should be compensated for their land – and who should pay for it – continued to inform opposition politics.

Settlement plan

While some radicals within Kanu, including Vice-President Odinga, insisted that the White settlers should not be paid and that land should be free to the landless, the British government pushed the moderates to agree on a settlement plan in which the new government would get loans to purchase land and offer it for sale to the landless.

This not only increased the number of landless Kenyans at the dawn of independence but also created political tensions over failure by the Kenyatta government to resettle squatters for free. It would also raise political temperatures in the Rift Valley as some Kalenjin politicians – led by William Murgor, also known as Bwana Firimbi – threatened to start war if Kikuyus and other tribes bought farms there.

In July 1963, a month after Jomo Kenyatta was elected Prime Minister, the matter was raised in Parliament by Gideon Mutiso who demanded to know whether “indigenous people were to be resettled in their own lands” and if settlement schemes should be for free. It was a tricky question.

After a meeting to deliberate on an answer, attended by Gichuru, Minister for Agriculture Bruce Mackenzie, Minister for Lands and Settlement Jackson Angaine and Parliamentary Secretary Ministry of Finance Mwai Kibaki, it was agreed that seizing land from settlers “is now history” and to “try to reverse it would destroy the economy”.

Economy tottering on collapse

It was this fear that Mzee Kenyatta would inherit an economy tottering on collapse as white farmers relocated that led to the snail-paced handover of farms and settlements.

Secondly, while it was thought that there would be enough money to buy all the land in the “Scheduled areas” also known as White highlands, the cash crisis kickstarted a private treaty land-buying spree that tilted the balance in favour of the political elite, senior civil servants and businesspeople.

The White settlers opted to sell their land, in the willing-buyer willing-seller policy to the elites, who could access bank loans, or to organised land-buying companies. Money was paid through law firms rather instead of the settlement fund.

Records indicate that most of the political leaders, businessmen and land-buying companies capitalised on the government’s inability – or reluctance – to purchase all the farms on offer and took advantage of the confusion to acquire land, either for a song or through grabbing. They could also target abandoned farms.

Free-for-all buying spree

Thus, the failure by British government to commit more money to purchase land in the White Highlands and lack of political will to settle the poor for free, is today regarded as the trigger to this free-for-all buying spree which left the penniless struggling.

The then argument was that if the land were given away for free, the value for land owned by Africans would be reduced to little or nothing, no one would be able to borrow on the security of his land and that nobody would lend the government money to lend to settlers for development of this land.

As Angaine told parliament in 1963: “There is no provision whereby the minister can exempt poor settlers from paying for their land. Moreover, the government is required to repay the money it has borrowed for the purchase of the land. For this reason, no exemptions can be made.”

The transactions that took place in this period would inform the tribal relations in Kenya – and the clashes that have been witnessed since 1963. That a government policy allowed individuals – led by President Kenyatta and his ministers – to acquire thousands of acres and left millions with unresolved land problems has always been thorny.

The institutions that had been set up to deal with adjudication, consolidation and registration of land finally failed to settle the landless. Fifty nine years later, politicians are still promising to solve the problem.

Will they?