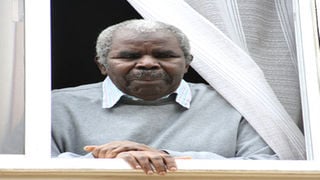

The late Gerishon Kirima at a balcony of his house in Kitisiru on August 7, 2010. The city tycoon passed away on December 29, 2010 while undergoing treatment at a hospital in South Africa.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

How Kirima built his multibillion-shilling empire

What you need to know:

- At the dawn of independence, he was employed by the Royal College as the resident carpenter, and he started operating a small workshop in Bahati.

- Kirima had, by 1967, emerged as one of the astute African businessmen. He had started as a carpenter and knew the art of creating wealth by being frugal.

In 1976, Gerishon Kirima placed a notice in the Kenya Gazette that he and his G.K. Kirima and Sons company would not be held accountable for any debt incurred by his relatives, family, or staff without his express authority.

That is how the billionaire ran his empire. Kirima was frugal – a billionaire who was the king of bean counters.

Thirteen years after his death, Kirima is back in the news after the High Court declared that he was the owner of the vast land in Nairobi’s Eastlands that had been occupied by squatters and sold to unsuspecting investors by brokers, cartels, and land sharks. It is true.

I have seen Kasarani MP, Ronald Karauri, question how Kirima acquired the land. One needs to see the land transaction files at the Kenya National Archives, and it is all there.

Kirima had, by 1967, emerged as one of the astute African businessmen. He had started as a carpenter and knew the art of creating wealth by being frugal.

At the dawn of independence, he was employed by the Royal College as the resident carpenter, and he started operating a small workshop in Bahati, the hub of African entrepreneurs. It was in the Bahati workshop that the family would eke extra cash.

They also run another workshop in Kaloleni where his first wife, Agnes, would attend customers. From here, she brought up her children.

Kirima was parsimonious, albeit thrifty, with the little money he earned. He opened bars and restaurants, taking advantage of the rural-urban migration, which had brought thousands of people to Nairobi to seek work.

Banks were looking at this emerging class of entrepreneurs to support – as white settlers sought buyers of the vast ranches they held. Again, the Kenyatta government had no money to purchase all the land on offer.

The land Kirima bought used to be owned by an Italian farmer, Domenico Masi, a cattle rancher, who had opted to leave the country.

Kirima purchased the land and cattle and became one of the major meat suppliers in Nairobi. But rather than enter the trade as a wholesaler, Kirima had opened his Kirima Butcheries and tapped into the emerging African middle class in Nairobi’s Eastlands and the city’s environs.

During this period of Africanisation of business, Kirima fought to break the Kenya Meat Commission monopoly by opening his abattoir in Njiru and entering into the most lucrative trade: meat supply. It was not surprising that he added 108 acres from British settler Charles Case, the son of an Ol Kalou rancher, William Herbert Case. His next purchase in the same area was the 472 acres in Njiru he purchased from Percy Everley Randal – a South African rancher who had sold most of his land to the UK-based Magana Kenyatta.

With these ranches, Kirima established himself as a rancher keeping beef animals, supplying Nairobi with meat, and breaking the Kenya Meat Commission monopoly, which had ignored steers from African-owned farms. Alternatively, they underpaid African farmers.

This pro-settler attitude would mark the demise of KMC for its history was the history of colonial meat supply. Previously, during the colonial days, the government had established the African Livestock Marketing Organisation to regulate the animals from African farms destined for KMC.

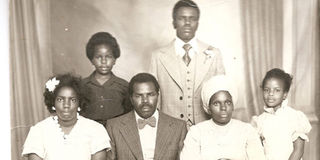

A younger Gerishon Kirima with his wives and children. Photo/FILE

Kirima had seen this opportunity, and he had brought together all the African butchers to demand their inclusion in the meat industry. As chairman of African Butchers – later Kenya National Butchers’ Union – Kirima became the voice of the multimillion-shilling industry.

Njiru was part of his ranch, the space in which he was to build his empire. Before independence, Africans were not allowed to buy high-quality meat from KMC, and the areas identified as “African locations” were supplied with low-quality meat – only fit for roasting.

After independence, this low-quality meat was identified in KMC parlance as FAQ, meaning Fairly Average Quality. That would be anything from hooves to offal meat, and each butchery had its quota, which was not guaranteed.

It was this monopoly that Kirima sought to fight since KMC was the only licensed supplier of meat in Nairobi butcheries. But there were pirate suppliers, and police and council askaris were always on the lookout.

But ranching was not as profitable as Kirima projected, and so he was left with real estate in an area that was not inhabited. The price of meat was government-controlled, curtailing the development of the meat industry.

Many other farms in the vicinity – but owned by cooperatives, including the Kiambu Dandora Farm and the Embakasi Ranching Company would also collapse to the same fate. And like Kirima’s Njiru Farm, they have faced the same problem with squatters.

Kirima ventured into the transport industry, and his Kirima Bus Company was one of the most flourishing in Central Kenya and competed with Dedan Njoroge Nduati’s Jogoo Kimakia Bus Service.

It was these two African-owned companies that would challenge the British company Overseas Trading Company (OTC) on the central Kenya route. But Kirima Bus Company did not survive for long after Kenyatta issued a decree that allowed Matatus to enter the transport business from Nairobi to other towns in 1973.

Kirima and other transport entrepreneurs, Muhuri Muchiri, Oginga Odinga, Tom Mboya, and Nduati, were some of the first casualties. But before he sold the buses, Kirima was in a group that asked Kenyatta to intervene.

But Kenyatta is reported to have told them to invest in Matatus if they think they are eating his business. Kirima then folded his transport company and was allowed to start his abattoir in Njiru.

As KMC naively marketed its “up-market” beef, the Kirima group snatched the growing lower-end market and promoted the consumption of roast meat to build a viable meat industry.

Because of that, Kirima became the love of many Nairobi dwellers and was elected a councillor and Nairobi Deputy Mayor.

Despite his dismal education, he was elected as MP in Nairobi. Meanwhile, he had ventured into coffee farming and real estate and his children would not be spared. They would join the other coffee pickers and at the end of the month, they would also be sent to collect rent from his rental houses in Nairobi’s Eastland.

Despite the wealth he had, Kirima was not sophisticated. He never showed off his wealth. It is no wonder that people wonder how such an inconspicuous man turned into a billionaire.

When he lived, one could spot him around his Kirima Building, opposite Jeevanjee Gardens, Nairobi, in the company of age-mates or taking tea in the eateries nearby.

Court succession documents showed that Kirima’s estate could rake in Sh20 million monthly. One day, Kirima came to Barclays’ Bank Market Branch with a bag full of money. He had apparently walked from the nearby office.

Then the daughter came rushing and asked him: “Why should you risk?” Kirima looked at the daughter and wondered who would dare take his money.

It is perhaps this kind of faith that saw him watch his estate invaded by squatters. His later years were drama-filled: Witchcraft stories, a new wife, deaths, and threats. As diabetes took a toll on him, people took advantage of his estate and started selling plots.

With poor eyesight and still hanging on to the properties, Kirima watched as politicians also used his land as bait to attract voters. Kirima was not alone. All the land owned by land-buying companies in Nairobi’s Eastland would be invaded in a similar fashion.

By going to court, the Kirima estate wanted to right the wrongs done to a pioneer African businessman.

It is the story of how systems in Nairobi have collapsed – to the extent that even Nairobi MPs do not know the history of that land. It is also the story of billionaires who failed to push their empires to new frontiers.

[email protected] | @johnkamau1