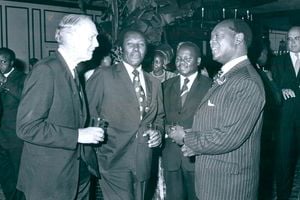

Then vice president Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and president Jomo Kenyatta.

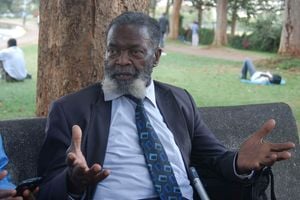

Detained, jailed, and politically isolated, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga was never silenced. Thirty years after his death, the nation that Jaramogi envisioned as he fought for radical change is still a dream.

Jaramogi had a stand: "Our independence struggle was not meant to enrich a minority. It was to cast off the yoke of colonialism and poverty. It is not a question of individuals enriching themselves but of achieving national effort to fight poverty in the country."

Caught between pseudo-nationalists, capitalists, and loyalists, Jaramogi opted to force change from without, and in 1966, he resigned as Jomo Kenyatta's vice-president to launch his political party, Kenya People's Union. From this platform, Jaramogi naïvely thought he could articulate his policies, engage in a national discourse with the ruling party Kanu, and call for an ideological shift. He was wrong.

The British had already set up a propaganda unit, the Information Research Department (IRD), which ran a three-year campaign, the Special Editorial Unit (SEU), which was used to frame him as a Communist and as a threat to Kenyatta.

In 1965, the unit authored a pamphlet disguised as from People's Front of East Africa. It praised Jaramogi as a "great revolutionary" who would get to power through a new political party, the Kenya Socialist Party. It also dismissed Mzee Kenyatta's government as "reactionary, fascist, and dishonest."

As it emerged recently from declassified British papers, this propaganda was the work of IRD, which sent 80 copies of the propaganda leaflet to several journalists and insiders in the Jomo Kenyatta government.

Finally, the article was published by the Daily Telegraph, and one of the Special Editorial Unit Officials went to check whether their cover had been blown. It wasn't. According to SEU's John Rayner, "Kenyatta had thought it to be the work of the Chinese, (Tom) Mboya had considered it to have been put out by Odinga (Jaramogi), and that Odinga had claimed that it was the work of the CIA."

Historians now appreciate that Jaramogi was fighting some shadowy propagandists who wanted to protect British interests in Kenya. As archival records show, the British had, for a long period, intercepted Jaramogi's luggage and letters. At one point, when he was a member of the Legislative Council (LegCo), Jaramogi was blocked by immigration and customs officials as he returned from a Cairo meeting, where he had held talks with President Nasser: "My luggage was combed through by customs officials; I was half stripped as they searched my person. My diaries and all papers were taken from me and stamped and sealed. And my passport was impounded."

Father and son meet at the elder Odinga’s Bondo home for the first time since Raila was released from detention after five years in February 1988. Raila inherited the phobia that was generated for his father by the CIA and MI5.

Jaramogi died on January 20, 1994 without knowing the contents of British Intelligence File KV2/40, which covers the 1960s period, that he described in his autobiography as "difficult". The difficulty, he argues, was because of a "concerted world press campaign to elevate Tom Mboya to the unchallenged leadership of Kenya Africans."

The first entry to the file was a letter dated November 10, 1960, written by the Director of Intelligence and Security, Mr B. E. Wadeley, to the colonial Security Liaison Officer in Kenya and Uganda.

"As you are aware," he wrote, "an operation was mounted on this person (Oginga Odinga) when he arrived at Nairobi Airport on October 26, 1960, on completion of a visit to the United Arab Emirates and London."

"Without his knowledge, 356 documents on his person at the time were photographed. We are now examining these and will be letting you have a report on their contents in due course."

That explains the incident at the airport on October 26, 1960 when Jaramogi's passport was impounded, and he was kept busy arguing with immigration and security officers. It is long forgotten that Jaramogi was returning from seeking scholarships for Kenyan students and from fundraising to support the nationalist struggle.

Interestingly, what was labelled a factional fight between Tom Mboya and Jaramogi was, according to documents declassified over the years, a larger plot to preserve British interests. It was a scheme by the British to create a political rift that would remove Jaramogi from the centre stage of Kenya's politics. His socialist ideals, which he argued would transform Kenya, were openly dismissed by the capitalist wing within Kanu.

Jaramogi Oginga Odinga (left), his wife Mary and their son Oburu Oginga at their Kileleshwa home in Nairobi.

At independence, Jaramogi had envisioned a "government for the working people." He was worried that the government was concentrating on "propaganda about its housing record" even though it had spent less on housing. He was also concerned that the Kenyatta government had refused to give free land to the landless and those displaced during the independence struggle.

He called for the "distribution of free land to the neediest, including squatters and those who lost their lands in the struggle for independence, either by expropriation or through land consolidation." This call was seen as Jaramogi's opposition to Kenyatta's post-colonial Hakuna cha bure remark on redistributing settler farms to landless for free. It was also against the British insistence on a willing-buyer, willing-seller land policy. While Jaramogi was not calling for the vacation of land already owned by Africans, his vision was that land acquired from European settlers should not be sold to the poor.

Also Read:The curse of Kenya’s vice presidency

It was these frustrations that made him raise his voice above those who thought that Western capitalism, the platform on which the colonial and neocolonial ideology operated, was the solution to Africa's underdevelopment.

Jaramogi called for a radical change in land ownership, and after he launched Kenya People's Union in 1966, he committed to "secure this change [and] to correct the highly unjust and inequitable present distribution of land." Jaramogi had hoped that competitive multi-party democracy, based on specific issues, would evolve in Kenya.

During this period, Kenyatta set up a secret Cabinet Security Committee led by Dr Njoroge Mungai, James Gichuru, Daniel Arap Moi, and Bruce McKenzie. According to historian Charles Hornsby "Its remit was to identify and respond to the main threats to Kenya's security. Kenyatta explicitly directed the committee that the threat was internal and came from Odinga."

In his 1967 autobiography, Not Yet Uhuru, Jaramogi complained that "forces of imperialism…have the whip hand over our economies." What Jaramogi advocated was for an economy in which Western interests were not paramount and where new African nations decided the price of raw materials they produced.

KPU leader Jaramogi Oginga Odinga (with cap) in an exchange with President Jomo Kenyatta in October 25, 1969, shortly before Mzee's bodyguards opened fire and killed about 50 people in Kisumu.

His other concern was the mushrooming of shanties in urban areas and the neglect of workers. He wrote: "In the towns, the workers are as over-crowded as they were in colonial times, three or four families sharing a house, and beds all around the walls." He blamed the political elite that this was a ticking bomb and could lead to an uprising. He argued that workers were willing to wait for the fruits of independence only if they were confident that the government was "composed of leaders genuinely concerned with their future."

Jaramogi felt that the leaders were less concerned on the setting up of industries which could offer decent jobs and accused the Kenyatta government of "evading responsibility for the development of this sector."

Rather than listen to Jaramogi, the leaders accused him of "seeking to replace the president" and undermine the government. "The same group of politicians who had opposed me when I advocated the release of Kenyatta from detention were now telling the president that 'Odinga wants to overthrow your government.

In Kenya, Jaramogi was labelled a Communist – a tag that he constantly denied: "The allegation 'Communism' has always been a convenient weapon. During the Colonial times, Kenyatta was termed a Communist, and the freedom struggle was labelled Communist inspired. Politicians have made use of the anti-Communist smear not because they hold confirmed political views but to use a stick to beat those campaigning for real consultation with the people and against corruption in public life."

But was Jaramogi a Communist? "I am not a Communist, but I have been a constant target of anti-communist forces for all the years of my political history."

The vision that Jaramogi had while setting up KPU never materialised after the entire leadership was detained following the 1969 Kisumu killings. The ban denied Kenya a chance to see a presidential contest between Kenyatta and Jaramogi and the first political tussle based on ideology. It was a long wait.

In November 1990, Jaramogi surprised Kanu after he announced that he intended to form a new political party. In his New Year's press release, he declared: ‘1991 is the year for political pluralism." He was right.

The push for political pluralism gained momentum, and Jaramogi returned from the political cold as the symbol of Kenya's second liberation. As the father figure in the formation of the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), he was instrumental in pushing Kanu to abandon the single-party regime. It was a battle that he won. It was part of the Kenya he dreamt about.

By vying for the presidency in the 1992 General Election on a Ford Kenya ticket, Jaramogi returned to the fold and gave a generation of politicians a chance to enter competitive politics. Most young politicians, identified as "young Turks," rallied behind him. His Ford-Kenya party was radical and progressive. As a human being, he faltered, too, as age and political traps were put in his way. On January 20, 1994, he passed on. To his credit, Jaramogi had emerged as the father of the second liberation, having struggled against Kenyatta and Moi to return Kenya to competitive politics.

Forgotten is that Jaramogi was a central pillar of Kenya's liberation war and played a crucial role in alerting Kenyans of the emerging corruption and elitism. For that, he was ostracised and banished. But history did not forget.

- [email protected]; Find him on X: @johnkamau1