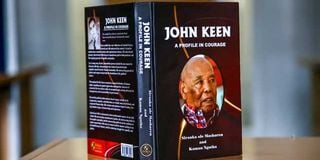

John Keen’s book ‘A Profile in Courage’ which chronicles the story of the journalist-turned-politician who died in 2016.

Political parties in Kenya organise grand events, their leaders dish out money and appear well-oiled as they make one declaration or another. Ever wondered who funds them?

The leaders hardly say it, but a book on politician John Keen – released almost eight years after his death – sheds light on who funded some party activities in the past, why the funding was made and how the money was used.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni is said to have sponsored an opposition party against President Daniel arap Moi.

John Keen: A Profile in Courage was launched in Nairobi on Friday. It is written by Sironka ole Masharen and Kamau Ngotho.

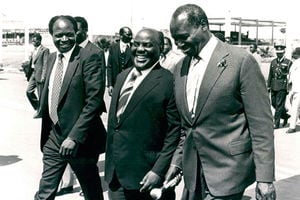

The book chronicles the story of the journalist-turned-politician who died aged 90 in 2016. It shows a side of politicians most Kenyans might never have known.

Keen observes that political outfits often got support – though the money was often misused.

In one instance, he notes that Jomo Kenyatta, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and Tom Mboya received financing from various powers – European nations for Jomo, the US for Jaramogi and the Soviet Union for Mboya. The common theme is that the politicians pilfered the cash.

“Even with this, Kanu was perpetually broke and at the mercy of auctioneers. It was no secret that Jomo Kenyatta, Odinga and Mboya pinched the donations. It was the beginning of a political culture that would blossom into insatiable plunder of public resources,” he says in the recollections that form part of the biography.

“I was involved in fundraising for parties I was associated with, but the pilferage so raised is a culture that has spread to the core of society. Attempting to uproot it was akin to sacrilege. Such an attempt has inherent grim risks – from social ostracism, business sabotage to death, depending on circumstances.”

To illustrate the point, Keen tells of an incident in which auctioneers descended on party premises. He saved the day by issuing a Sh1 million cheque. Keen thought the party, through his friend Mwai Kibaki – who was an official – would refund him.

“Kibaki, driven by a false sense of entitlement, refused to refund the money, saying the bailout was a donation to the party. After I had retired, I took him to court. The court ruled in my favour and ordered him to refund the principal sum plus interest, totalling Sh1.8 million,” he says.

Keen retired from active politics at the age of 70 in 1996.

The biography says when the Democratic Party (DP) was formed (in Keen’s home), it had a long list of backers “that wanted a quick end to the Kanu dictatorship”.

“The DP donors were mainly rich businessmen from Central Kenya whose economic fortunes had suffered considerably under Moi,” says the book.

That is where President Museveni emerges. The biography says that in 1992 after the formation of DP, and with a General Election approaching, Keen flew to London alongside Njenga Karume to meet an emissary of Mr Museveni. Museveni and then-Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi were against Moi.

“They brought to us (through the emissary) the equivalent of Sh10 million in American dollar currency. Museveni and Gaddafi wanted a regime-change in Kenya and secretly supported dissidence. We exploited the diplomatic hostility to good effect,” he says.

“Museveni, then a youthful and Marxist-leaning ideologically, loathed Moi because he suspected the Kenyan president was in favour of (Milton) Obote being president of Uganda.”

Among the gems in the book is where Keen compares Kibaki to a wheelbarrow. This is used to describe the sluggish nature of Kibaki in the days he had defected from the ruling Kanu party to lead the DP. Keen – then the secretary-general – felt frustrated with the man who would later become Kenya’s third president.

“To work with Kibaki, you must be prepared to push him like a wheelbarrow. He lacked self-drive and conviction in a cause,” Keen notes in the recollections.

The book packs history, power and money into one hardcover compilation, and there is no lack of humour. An instance is when Keen and Kibaki had a meeting with Jomo in the early 1960s. Jomo asked if they were married.

“When they answered in the negative, he laughed loudly and removed a cheque book from his drawer. He wrote each a cheque of Sh1,000 – a lot of money in those days. He said, ‘Never come back to my office until you are married men!’,” he says.

The biography also attempts to illustrate the stakes in the historical moments in Kenya, like the arguments for and against single-party rule. It includes the weight it bore when Kibaki had to quit from the government and join DP, when Moi’s deputy George Saitoti rebelled against Kanu and the “blunder” Raila Odinga made by shelving his presidential ambition for Kibaki.

Keen was at some point opposed to one-party state. When it happened, he was against a return to pluralism. He decamped from DP and returned to Kanu in 1995.

Hansard records reproduced in the book show that Keen was on the government’s side after the 1990 murder of Foreign Affairs Minister Robert Ouko, saying in Parliament: “People should not preoccupy themselves with rumours on who killed Dr Ouko, yet we have many problems to deal with”.

The book carries the last words Keen said as he died on December 24, 2016: “I have done everything I needed to do, with the best of my ability. Nothing else is left for me to do.”