Breaking: Autopsy reveals how Cyrus Jirongo died

Premium

Nkaissery: Pitfalls that came with sensitive docket

The then Internal Security Cabinet Secretary Joseph Nkaissery.

On the morning of Wednesday, December 24th, 2014, General stood on the lawns of State House, Nairobi.

In his right hand was the Holy Bible, aloft, as he took an oath of office to serve in the Jubilee government of President Uhuru Kenyatta as a Cabinet Secretary in the Ministry of Interior and National Co-ordination of Government.

This position is the apex of the country’s security docket.

I sat with several government officials and representatives from Kajiado on the veranda overlooking the lawn. I looked at General.

He didn’t appear to be as spell-bound as I was. He wore his trademark dead-pan expression, concealing all emotion, concealing his thoughts.

Also read: Exclusive: General Joseph Nkaissery and I

But his voice — clear, earnest, steady — told me what I already knew. This moment was the culmination of so much that he had worked for.

He was not the first member of the Kenya Defence Forces to serve in the civilian ranks of government.

Though he may not have had much contact with those who had made a similar career shift before him, General’s 29 years in the army and 12 years as a lawmaker and people’s representative had prepared him well for this opportunity to steer policy decisions on security in Kenya.

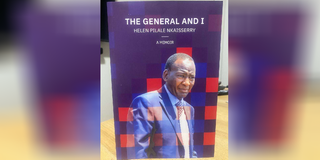

The front cover of the book.

General relished constituency work. He used to say, “Nimeandikwa kazi na wananchi [I am employed by the public].” Parliament, however, had begun to tire him.

He complained to me a lot about the careerism of some of his peers, their sloppy timekeeping, the crippling lack of quorum in the debating chamber, and a general lack of seriousness in the work of being a people’s representative. He longed for something more challenging.

Why did General get the call to serve in the Jubilee government? President Kenyatta gave his reasons in July 2017.

“When we formed government [in 2013] the one person I really, truly, felt we missed was General Nkaisserry… We had all sorts of issues at the time… especially in the security sector that required a major overhaul of how we did things. I was forced to go back and say, you know we had discussed, way back in the ‘90s of how we would do these things, and I called General Nkaisserry, and I said, ‘Let us forget about these barriers. Why don’t you come and let’s just rekindle what we started?’ ”

General, freshly elected on an ODM party ticket, was serving his third term. Jubilee had won the 2013 presidential race and Kenyatta formed a government allied to his party’s vision ...

President Kenyatta says that the day he made the call to ask General to join his Cabinet, “General did not hesitate even for five minutes. His point was, ‘I was waiting for you to call me so that we can get to work.’ ”

Even before the President made that call to General, there had been people talking to General to gauge his thinking about joining government ...

It was a fair amount of pressure but as General told me, “Let me just play it cool. Let me first of all understand the legal perspective before I go to say ‘Yes’ to something.”

There was a delicate balancing needed for the timing between the President’s announcement, General’s resignation, his vetting in Parliament, his formal appointment, and his swearing-in. Every step was fraught with complexities.

The strategising took a new subterranean energy. Unlike when he was leaving the military for politics amid numerous consultations with Maasai elders and tête-a-tétes with his friends, this time General kept everyone in the dark ...

The President’s announcement finally came on December 1, 2014. ODM legislators embraced it, boasting that the President was poaching from them because their party held “the tyranny of brains.”

General’s elevation was embraced by many, even before he jumped the hurdles of vetting by Parliament’s Appointments Committee.

General saw devolution as a great benefit in the work of national security. He wanted governors to help the mobility of the police with, for example, “every governor having two choppers in his own county, just in case when a crisis or emergency occurs in his own county.”

This view, which General expressed publicly on Boxing Day 2014, proved uncannily prescient three months later when terrorists attacked Garissa University.

General was in his customary flip flops and macawis working out at dawn on the morning of April 2, 2015 when we learnt of the Garissa attack. I saw the military man in him move into action. He was ready in a flash...

There was no hesitation when he called the police to say: “Prepare a helicopter. I’m going.” I tried to urge him to have breakfast. “Araram. We Mama hujui, sasa tuko operation! Wachana maneno ya chakula. Sasa tuko operation [Quiet. Don’t you know we are now in operation mode? Forget about food].”

Much later, when he called to let me know he was safe but wouldn’t be coming back to Nairobi that day, he was brief, almost curt on the phone.

I knew he hadn’t packed any clothes or toiletries for the trip, but I knew better than to ask him in that quick phone call how he was going to manage or when he would be back.

He was away for two days. As I commiserated with him over this harrowing assignment, he told me:

“You know, I told Mr IG [Inspector-General of Police] when he was getting into a plane with me, ‘Bwana IG, have you carried your change of clothes?’

He doesn’t know that these are not places you come and leave immediately, you know, prepare. So the IG tells me, ‘But General hata wewe hujabeba [even you haven’t carried an overnight bag].’ I said, ‘I’m fine! Nitaomba Wariamoja shati moja [I will ask a Somali to loan me a shirt] and as long as they give me something to shave my beard, I’ll be fine that’s the only thing that will disturb me.’”

That kind of light, inconsequential banter was the way General always put others at ease while bracing himself for the worst, and mapping strategies for a successful mission. In Garissa, he was joined by some elected representatives, including the Garissa Town MP Hon Aden Duale.

I learnt later that when they got to the university and Duale followed General through the gates, General said:“Eh, Mheshimiwa [Sir]! Now this is where we divide the goats from the sheep. You cannot follow me because, where I’m going, no civilian can go.”

General wasn’t going to rely on reports from his juniors about what had happened. If he was going to speak to the country about this attack as the minister in charge of security, he had to walk in there to see it for himself.

Someone tried to stop him at the entrance to the dormitories. His response was: “No, I want to warn you I am going to go everywhere.”

This time, what awaited him jolted even his own steel military mind and heart. One of the Administration Police (AP) officers in General’s security detail, a Maasai, told me later: “For once, we heard Mzee grunt, deep in his chest, and then he exhaled.” When a Maasai warrior makes that sound, you know the worst has happened and his response might be extreme.

General moved into the County Commissioner’s office to manage the rescue mission.

He was not going to leave Garissa until all 147 students who died that day had been identified, their bodies moved to mortuaries and the rest of the students and staff of the university had been accounted for. His hosts, the MPs, did buy him two shirts and a shaving kit.

That attack stayed on General’s mind for a long time. He made a quick visit to the UK to decompress, or perhaps for some other security-related reason.

General shielded me from the details of what he saw in Garissa and how the lapse between intel and the attack might have occurred. But, time and again, he regretted the pace of the courts in dealing with the suspects of this, and other criminal gangs, arrested over terrorist attacks.

“I wish there was some way of shortening these processes. Because the faster things are dealt with, the better,” he would say.

The disappointment

I wish I could describe fully how our lives changed from that Christmas Eve in 2014 when General was appointed a Cabinet Secretary. It was like the difference between day and night, between cold and boiling hot.

I used to be someone who could jump into my car at a moment’s notice and drive from Karen to Bissil with the radio tuned to my favourite Hope FM station.

Now, I became a person whose itinerary is the subject of intense consultations between drivers and the security men who were always outside our front door. It was as if the barracks had moved into our homes!

This sight of armed people at the gate in the vicinity of where we lived was something I had left in Lang’ata Barracks so many years ago. I had forgotten how to live so close to uniforms and guns. I frowned at these changes.

General held my hand and urged me to be patient, the men were just doing their jobs. I tried. We converted one of our outhouses in Bissil to create living quarters for the security detail.

General never allowed power to consume him ... If you made the mistake of bringing him bottled water at a public event as he sat on the podium, you would be surprised to find it there, untouched, at the end of the function.

It wasn’t that he feared being poisoned; it was that he was not going to elevate himself above the people who had gathered to listen to him. If he was thirsty, he argued, so were they; and they were out there roasting in the sun.

It was bad enough that he was under the canopy of a veranda or a tent, and they weren’t, he was not going to add insult to their injury by sipping water or worse, eating before they did. Being like everyone else was always General’s default position...

Our friend Sammy Risah says that, whenever General joined him and other members at their famous Landing Club, he would be alone, no driver.

As they parted ways, late one night when General was CS, Sammy was appalled that his old classmate was unaccompanied.

There is a forest between Landing Club and Karen, and Sammy knew that General, like all good Maasais always knew a back route, a shortcut, an off-the-beaten track passage that led home.

“I told him: ‘Why do you use this road at night, and you are alone?’ And then he asked me:“Unataka niende na nani [Who do you want me to travel with]?”

I said: ‘Come with the driver or your bodyguard’.

‘I am a General! Mimi nichungwe na askari [How can I be protected by a policeman]?!’”

The moment General got to Kajiado, as his former campaign manager Mustafa recalls, he would dismiss the chase cars and bodyguards and tell them: “Niko nyumbani, niko sawa [I am fine now, I’m at home]”.

That assurance would never stop his security team from doing their job. They would retreat to a discreet distance so as not to irritate him, but they would keep an eye on his movements.

I think it was in his time as an MP that General developed an interesting self-soothing habit. He would walk through the front door, usually, in the evening singing, “Asante ya punda ni mateke [the kick is a donkey’s shows of gratitude].That was the cue for me to ask:“Who is it this time?” In other words, who has betrayed you? And then he would start a story about the latest political backstabbing. ..

Despite this widespread political culture, General never stopped being straightforward in his dealings, even with political opponents.

His agemate Moses ole Sekento explained how, when there was a problem, General would seek him out. “We were not always on the same side in politics, but he would come, sit across the table from me, and then after we stare at each other for some time, I ask him: ‘What do you want?’ He would say straight: ‘You did this, and you were wrong.’ Then we discuss and finish it.”

Mustafa chuckles at the memory of the way General managed back talk. “You bring General muchene [gossip] and he picks his phone.

As you talk he is flipping his phone and answering you distractedly, ‘Eh? Naani [So-and-so]? He said that?’ And then he makes a call, and you hear the opening words and freeze, ‘Naani? So-and-so is here with me, and he tells me you said….’. You could not bring General rumours and lies because he would verify them on the spot.”

Speaking of instant verification, one time, I was travelling to Bissil when I got a call from an Airtel number. The caller spoke in halting Maa but I understood that he was saying a cousin of mine who, it had been said was a casualty in the El Adde attack on Kenyan peacekeeping soldiers, had been found alive.

The caller asked that I request a military helicopter be sent to pick my cousin in the bush where he was stranded allegedly with several Maasais. In gratitude, I sent the man some money via M-Pesa, momentarily forgetting he had called on an Airtel line. Next, I called General and shared the news excitedly. His reply was curt.

A few moments later, I got a call from someone at DoD and gave him all the information he asked for, including the number of the caller.

Thank goodness I had gullibly sent the man some money. That was how they tracked him down. When I asked General whether the man had led them to my cousin, he told me the entire operation was a hoax.

I was being used in the hope that my proximity to the CS would guarantee action and then the military helicopter would be shot down. What? So what happened to the man? In his usual reticence on security operations, General just brushed his hands to indicate, ‘finished’.

If his political life had exposed us to hypocrisy, now we were exposed to nefarious schemes.

Who could I trust?

At work, General was encountering his own share of dubious schemes. Saitoti tells me of one particularly outrageous one which left General disappointed to the point of being shaken. A very young woman from Kajiado went to Harambee House and insisted that she wanted to see General. He had an open-door policy, but he always asked for a brief on what a visitor wanted. Saitoti explains the policy, “He gave me the leeway to vet who comes in. Any talk of business and I just tell you can’t see him, but I will report it to him. He was not very good at delegating because he still wanted to know, ‘All those people in the waiting room, what did they want?’.”

The young woman from Kajiado insisted that her matter was personal, though she was a police constable stationed at Kamukunji in Nairobi.

“When I took her in to General, she said she wanted to be transferred.

General: ‘What is the problem?’

Woman: ‘I just want to go to a better place.’

General: ‘So where, do you have a place in mind?’

Woman: ‘Either Mlolongo weigh bridge, or Juja.’

General: ‘Why Mlolongo and Juja?’

Woman: ‘Hapo sitakosa kitu kidogo [It’s easy to get bribes there]’.

“I could see the shock in his face but he managed to say, ‘Sawa sawa its OK, muende muelewane, just go with this girl and see how to deal with that issue.’ I went out and told the girl ‘Just go to your station I will get back to you’.

General pondered that issue for a long time and he started thinking up reforms that transform the police service to rid it off rotten elements such as bribe-taking officers.

Also Read the first instalment: Day a furious Kenyatta blasted Gen Nkaissery at State House

Also Read the second instalment: The tense phone call that reassured me of Nkaissery's love for me

Also Read the third instalment: The General and I: Day grave seller sent me on a frenzied drive across America

©Helen Nkaisserry / Santuri Media, 2022