Lawyer Pheroze Nowrojee who was representing Mr Raila Odinga at the Supreme Court.

When Pheroze Nowrojee’s grandfather, a train driver, lost his job with the Uganda Railway after 16 years of service, the family was forced to pack up their lives and return to India. But they did not go quietly.

Pheroze’s father — Eruch Nowrojee — wrote a letter to the King, asking for justice and fair play.

By then, the Nowrojee family had relocated to India but returned to East Africa after the senior Pheroze was recalled and reappointed as an engine driver.

From that moment, the Nowrojee family never returned to India and always chose to fight and root themselves in East Africa — a land that had already become intertwined with their identity, struggles, and hopes.

When he died on Saturday, April 5, lawyer Pheroze Nowrojee — the son of Eruch — had become an inseparable part of that legacy.

Senior Counsel Pheroze Nowrojee.

Relentless in carrying forward his father’s fighting spirit, he championed the cause of the downtrodden in the corridors of justice. It is a story he tells vividly in his book, A Kenyan Journey, where he reflects on the enduring lesson passed down from his father: that power must always be challenged, and justice must be pursued — no matter the cost.

“Like his father before him, [my father] too had little liking for tyrants, grand or petty, or for injustice. And like his father before him, Eruch too was tied to the country.”

Journey of leadership and justice

Pheroze’s intellectual journey began far from the Kenyan courtrooms where he would later earn his place in history. He pursued law at the University of Delhi, one of India’s most prestigious institutions, immersing himself in the philosophies of Mahatma Gandhi, whose doctrine of non-violent resistance to oppression deeply resonated with him.

He was equally drawn to the political thinking of Jawaharlal Nehru, whose vision of a secular, just society shaped Pheroze’s understanding of leadership and justice.

Senior Counsel Pheroze Nowrojee. PHOTO | FILE

His quest for knowledge then led him to the London School of Economics, where he encountered a wider array of progressive thought. He was later admitted to the Bar and Lincoln’s Inn.

Here, he refined his legal mind and developed a deep appreciation for the principles of human rights and constitutionalism. These were not just academic interests — they were the tools with which he would later confront some of the most repressive regimes in Kenyan history. He later received a master’s degree from Yale University.

Fight for human rights

When he returned to Kenya, Pheroze Nowrojee quickly established himself as more than just a capable lawyer; he became a defender of the oppressed, a man for whom the law was not just a profession but a calling.

It was during the harsh years of the 1980s, under the repressive regime of President Daniel arap Moi, that Pheroze stepped fully into the national spotlight. The government’s ruthless crackdown on dissidents — particularly those linked to the underground Mwakenya movement — saw hundreds arrested, tortured, and detained without trial. Most lawyers kept their distance, wary of attracting the wrath of the state. But not Pheroze.

He stood firmly beside the accused, offering not just legal defence but moral support. In the courts, he challenged the very constitutionality of the sedition laws weaponised against his clients. He argued passionately that the suppression of free speech and political expression was not just a legal issue but an affront to the soul of the nation.

Among those he defended was Koigi wa Wamwere, the unyielding activist whose confrontations with both the Kenyatta and Moi regimes were legendary. Pheroze became his steadfast counsel, navigating treacherous legal terrain to protect Koigi’s right to speak, to dissent, and to dream of a freer Kenya.

In those days, his client list read like a roll call of Kenya’s political dissidents and reformers: from Koigi wa Wamwere to Raila Odinga, whose detentions without trial were a grim hallmark of Moi’s authoritarian rule. In each case, Pheroze fought tirelessly, often risking his own safety.

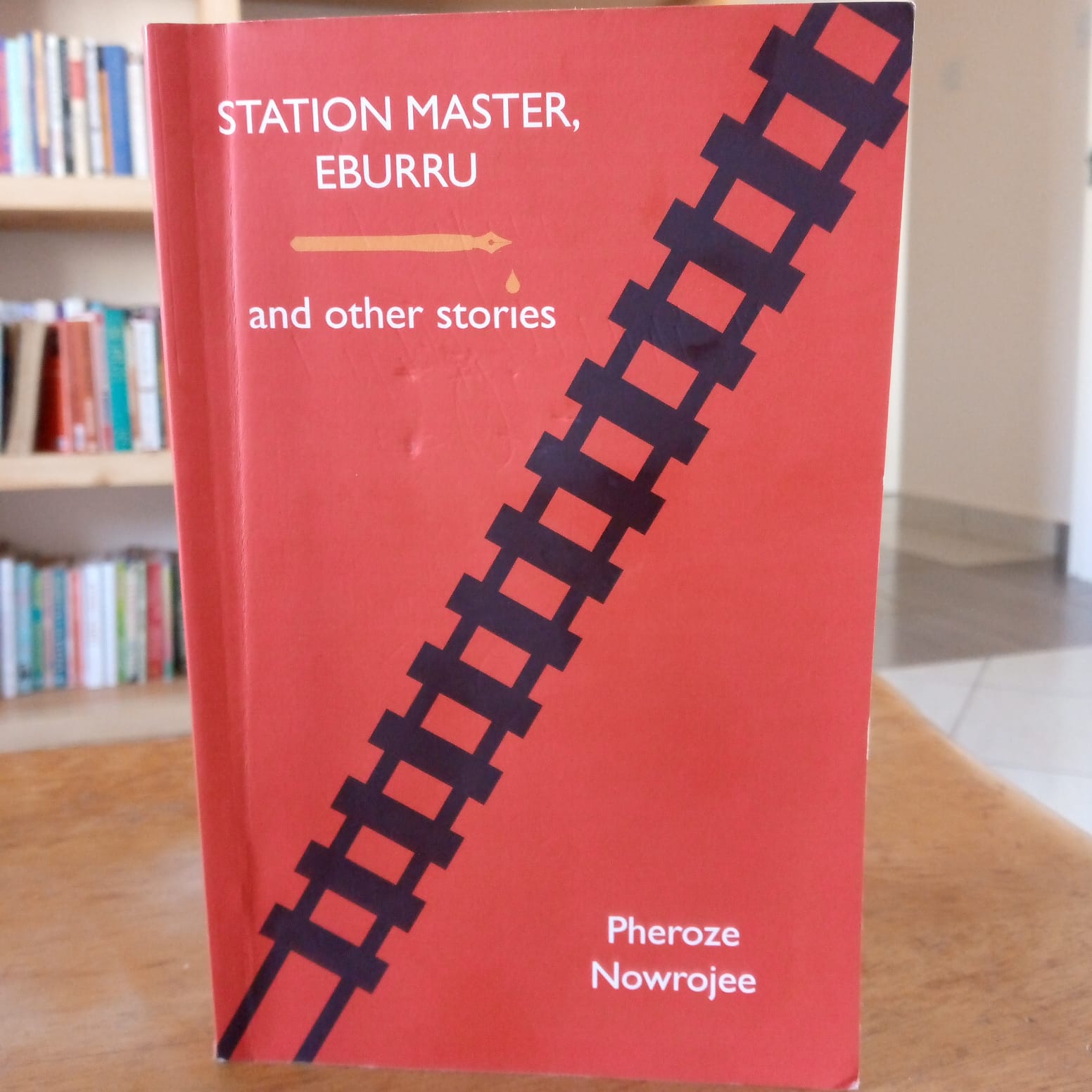

In Station Master, Eburru and Other Stories, lawyer, poet and author Pheroze Nowrojee paints an intimate portrait of the colonialism experienced in Kenya.

In the court rooms, Pheroze publicly and persistently questioned the legality of detention without trial. His arguments helped expose not only the unjust nature of this colonial-era provision but also the broader authoritarianism of the regime that clung to it.

But Pheroze Nowrojee’s critique of power did not begin or end with the Moi government. He was equally unsparing in his assessment of the Jomo Kenyatta regime, which he accused of fostering a culture of elite enrichment at the expense of the public good.

"He chose to let his government move resources from the poor to the rich. His followers moved from legitimate sources to illegitimate sources. They took public land, trust land, government money, donor money, parastatal money, always actively disregarding the fact that land and money were the land and money of the people," Pheroze once observed with unflinching candour.

For Pheroze, the struggle for Kenya’s liberation did not end with the lowering of the colonial flag — it continued in the daily fight for integrity, equity, and justice in governance.

Teamwork

Pheroze Nowrojee was not alone in this fight. He was part of a formidable collective of radical lawyers who dared to imagine a different Kenya: Paul Muite, Gitobu Imanyara, James Orengo, John Khaminwa, and Mohammed Ibrahim, among others. Together, they formed the vanguard of Kenya’s legal resistance, challenging the regime’s excesses in courtrooms and public forums alike.

Lawyers Philip Murgor (left) James Orengo and Pheroze Nowrojee.

They defended political prisoners, questioned the legitimacy of one-party rule, and fought for the expansion of civil liberties. Through their collective efforts, they laid much of the legal groundwork for Kenya’s eventual political opening in the early 1990s.

In one case, Martha Karua recalled: "I remember Pheroze Nowrojee finding us outside the court and coming in to help us and to lead us. He really rescued us. He led us in a very gallant manner."

Under the Moi regime, Nowrojee never lacked a human rights case to defend. These ranged from the right of assembly, sedition, to other Bill of Rights cases. In 2001, he had gone to a police station to check on his clients when he was arrested and beaten by the police. In Parliament, Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi protested: "Why was Pheroze Nowrojee, a respected elder in this country and a man with a heart condition..."

When Dr Willy Mutunga was picked as the President of the Supreme Court, it was whispered in the court corridors that Pheroze, had it not been for his advanced age would have been a better candidate due to his depth of legal philosophy, his international legal stature, and his calm, deliberate temperament.

Pheroze stole the limelight in 2017 during Raila Odinga’s presidential election petition when for 40 minutes he delivered a submission that many believed helped to overturn Uhuru Kenyatta’s victory – the first time an African court had nullified a presidential race.

As Kenya continued to grapple with questions of justice, equity, and governance, the legacy of Pheroze Nowrojee looms large. He leaves behind not just a rich body of legal scholarship, but also a living tradition of courage in the face of tyranny.

@johnkamau1