Premium

From 1982 coup to Moi's broken rungu: The day I spoke to his bodyguard

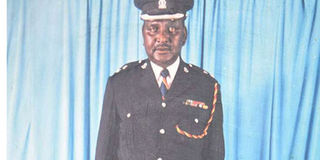

The late Senior Superintendent of Police Leonard Yator. He died at an Eldoret hospital on February 7, 2019. PHOTO | JARED NYATAYA | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Yator joined the colonial police at age 20 where he proved a diligent worker and was seconded to the escort of the colonial governor.

- At independence, he was inherited by the escort unit of the First President, Jomo Kenyatta, before he was made personal bodyguard to Vice-President Moi.

As we approached his home in Chuiyat village, Uasin Gishu County, I joked with the cheerful young man we had requested to be our guide. “Does the old man open his mouth except when chewing food?”

In all the years I had watched President Daniel Moi on television, not once did I catch his ever-there bodyguard blink or make a facial expression, let alone open his mouth. Senior Superintendent of Police Leonard Yator was a walking statue.

We found him in his compound supervising the feeding of his cattle in the afternoon.

Like the soldier he’d been all his adult life, you could tell he was suspicious of the strangers who had come to his home without invitation, but was careful not to show it until he established our motive.

“Welcome young men. But I don’t think we have met before,” he said as he led us to sit at the veranda of the main house.

INTERVIEW

From experience, I have always found it advisable not to beat about the bush when dealing with cops, serving or retired.

Being economical with the truth only heightens their suspicions. To the contrary, being upfront with truth makes them loosen up.

“We’re journalists from the Nation newspapers,” I said looking at him straight in the eye.

“We’ve come because we think you have a great story to tell as the man who has just retired after protecting our President for so many years.”

Not to give him a breather to think of how to respond, I fished from a manila envelope pictures of him standing next to the President at home and abroad.

“These are very good pictures. Where did you get them?” he asked. “We have so many of them in the Nation library,” I replied. His face brightened with nostalgia as he gazed at each of the photos.

“This is Buckingham Palace where we were guests of the Queen. And here we were in Sofia, the capital of Romania, where President (Nicolae) Ceaușescu and his wife are receiving us at the airport,” he said pointing at another photo where President Moi and his host are in knee-length heavy winter coats.

DILIGENT

The photographs did the trick. The old cop loosened up and agreed to an interview. I began by asking him to give us his background.

He had joined the colonial police at age 20 where he proved a diligent worker and was seconded to the escort of the colonial governor.

At independence, he was inherited by the escort unit of the First President, Jomo Kenyatta, before he was made personal bodyguard to Vice-President Moi.

He would remain in the same capacity when his boss became President and served until two years before the boss, too, called it a day in 2002.

I got into the meat of it by asking the retired policeman to recall the tensest and most dangerous moments during his tour of duty guarding Moi.

His first pick was a trip to Libyan capital Tripoli in November 1982 where President Moi was to hand over the chairmanship of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) — the predecessor of African Union (AU) — to Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

CIA PLOT

The circus had started the previous year when the OAU summit came to Nairobi and, as was tradition, host President became chairman of the continental body.

The next summit was scheduled for Tripoli to take place from August 5 to 8, 1982. But the US and her allies were determined that the rabidly anti-Western Gaddafi must not head the OAU.

During the Nairobi conference, the US intelligence, CIA, had sought and obtained permission to eavesdrop on the Libyan delegation.

Come the time to assemble in Tripoli, there was no two-thirds quorum for the summit to take place, forcing a postponement to November of the same year.

In any case, even were the summit to have a quorum, President Moi wouldn’t have been available to hand over.

By sheer coincidence, four days to the Tripoli date, there was an attempted military coup by the Kenya Air Force, which made it improbable for Moi to travel out of the country.

QUORUM

In November, President Moi had regained composure and travelled to Tripoli for the rescheduled summit. This time round, the turnout was even worse.

Of the 34 member states required for a quorum, only half showed up.

The Libyan leader went berserk having burnt a fortune in putting up a grand new conference centre and imported a fleet of limousines to ferry dignitaries to the continental meeting.

In his usual eccentricity, Gaddafi made the impossible demand that President Moi hand over the OAU chairmanship to him, quorum or not. The Kenyan leader refused to budge.

In one more stroke of madness, on the day President Moi was leaving the conference hall for home, rowdy youths showed up from nowhere chanting slogans in Arabic and charging in the direction of the Kenyan leader.

MOB

Yator recalled during my interview with him: “The unruly mob was dangerously moving in our direction screaming and hurling insults at President Moi in Arabic.

"The President’s safety was threatened and I had to act. I drew my two pistols and stood between the President and the unruly youths, my fingers on the trigger.

"President Gaddafi, who was just next to us chatting up Ethiopian leader Mengistu Haile Mariam, sensed danger and quickly waved his boys away.”

On the plane back home, a fuming President Moi remarked that he will only hand over the OAU chairmanship to Gaddafi over his dead body, bodyguard Yator recalled.

The Kenyan leader was to make history as the only one to have served as chair of the continental body for two consecutive terms, before handing over to the leader of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa.

Only weeks before the nasty encounter in Tripoli, Yator had the longest and most trying of all the nights he served his boss.

COUP

A few minutes past three on the night of August 1, 1982, word reached President Moi’s private Kabarak home in Nakuru that rebel soldiers in the Kenya Air Force had overthrown his government.

Thinking fast, bodyguard Yator figured it wasn’t safe for the President to remain in the farmhouse as rebel soldiers could decide to bomb it.

He wanted to evacuate the boss to the safety of a maize plantation at the far end of the 3,000 acre Kabarak farm, as they waited for the presidential escort commander Elijah Sumbeiywo to arrive from State House, Nakuru.

The President declined, insisting that if he was to die, it must be in his house.

President Moi only saw the point when the escort commander came and said the maize plantation wasn’t safe enough, and that the President be evacuated to the bush far north along the Nakuru/Eldama-Ravine Road.

PLANE SCARE

Yator and a few of the presidential guards remained with the President in the bush as Sumbeiywo returned to the farmhouse to monitor developments in Nairobi.

All along, Yator stayed shoulder-to-shoulder with the boss ready to take the first bullet fired should it come to that.

A decision had just been made that Yator and his men move the President even further north to Pokot territory, when word came that loyal soldiers were overpowering the rebels.

Back in the bush, it was the scariest night the bodyguard remembered ever spending with his boss. But to his delight, the President never showed undue panic.

It was a stoicism he had discovered in his boss much earlier when he was vice-president.

They were overflying Suguta Valley in the arid north when the light aircraft developed a mechanical problem, and the pilot had to make an emergency landing in the middle of nowhere.

The bodyguard remembers his boss clutching onto the window rail so hard during landing that it broke.

But he never panicked even as it took time for the rescue team to trace them in the bush, Yator recalls.

***

It was the same case on the night Vice-President Moi received information at his Nakuru home that President Kenyatta had died in his sleep at the Coast.

As the automatic acting President, Mr Moi was required to immediately head to Nairobi. With only three bodyguards, he hit the road to the capital city.

Yator sat next to him with a shotgun. The journey to Nairobi was as tense as it could get, recalled the bodyguard.

“But you couldn’t see it on Moi’s face. He remained calm, not once betraying what was going on in his mind, more so aware of the responsibility that lay on his shoulders now that his boss was gone.”

The same calm would show many years later on the budget day of 1997 when opposition MPs conspired to disrupt the speech once Finance Minister Musalia Mudavadi took to the microphone, with the President in attendance.

Come the hour, the all-time “bad boy” James Orengo rose on a point of order to stop the budget speech.

CHAOS

What followed was a chaotic session where opposition MPs heckled, placards in hand, and got into fistfights with parliamentary orderlies when they attempted to run away with the ceremonial mace, which effectively would have invalidated the House sitting.

All along, agitated presidential guards stood ready in the Speaker’s gallery waiting for a signal to jump over the rails to the chambers.

“We were annoyed at the provocation by opposition MPs and were ready to act. However, we were under firm instructions not to make any move unless instructed by the escort commander.”

INDIA

But there were also light moments during Yator’s stint as the man most trusted with the President’s safety.

Once during a State visit to India, President Moi’s famous rungu accidentally dropped, cracking the ivory handle (the rungu’s head-end was of gold).

For President Moi, appearing in public without the rungu was the equivalent of walking naked.

Yator was immediately dispatched to Nairobi to bring another rungu and a spare one. Henceforth, the presidential entourage would have a spare rungu when travelling, just in case.

***

Yet in another comical moment, an amorous member of the presidential delegation caused consternation at the airport in Lagos, Nigeria, when a call girl for whose night services he had declined to pay broke the security cordon and ran screaming to the VIP bay as President Moi and his host, Ibrahim Babangida, watched in amusement.

Yator recalled President Moi laughing loudly once they were airborne and telling the randy member of his entourage: “Chief, always pay for services rendered to avoid such embarrassment in future!”

***

Another time during a papal mass at Uhuru Park in 1995 by Pope John Paul, confusion in the arrangement at the VIP lounge had President Moi head for the papal toilet instead of the presidential dais.

But an alert Yator spared the boss embarrassment by quickly guiding him in the right direction.

***

As we parted with the old cop, I asked him whether he contemplated joining politics now that he had retired from police service.

“Not at all,” he replied with a sense of finality, “I will die a soldier”. He kept his word until he breathed his last at an Eldoret hospital on February 7.