President Uhuru Kenyatta and ODM party leader Raila Odinga during BBI launch.

| File | Nation Media GroupPolitics

Premium

How Kenya will look and feel like under a BBI environment

On March 9, 2018, President Uhuru Kenyatta and ODM leader Raila Odinga emerged from the depths of Harambee House to address an expectant nation. Months of political wrestling between them had divided the nation and heightened tensions, and their press conference, many hoped, would bring healing and repair the cracks.

In a televised speech, the two, after announcing that they had ended their differences and planned to work together for the nation’s common good, said they would roll out a project that would eventually become known as the Building Bridges Initiative, and which would be aimed at creating “a united nation for all Kenyans living today, and all future generations” .

That speech on the steps of Harambee House has finally metamorphosed into the Constitutional Amendment Bill, 2020, which is now billed as the answer to the perennial electoral, governance and economic challenges that have bedevilled the country since independence. In it many see hope, a rebirth of the nation, and a repurposing of its social, economic and political ambitions.

Call to action

In a way, therefore, nearly three years later since, and as the country prepares for a referendum, that big promise and the product of the Handshake are being tested by a national call to action that hopes to repair institutions and heal emotions.

The Nation spoke to experts on governance and leadership to get a feel of what the new Kenya, should the BBI be passed at the referendum, would look like. There were mixed opinions on the process of getting the proposals passed, as well on whether the country that emerges on the other side would be ideal. Some felt that the constitutional changes would herald the beginning of a new democratic dispensation that promotes equality and equity, others argued that, while those ideals are noble, they would be too costly to maintain.

The BBI Bill has so far been considered by 42 county assemblies, 40 of which have approved it. Baringo and Nandi voted against it while Mandera, Uasin-Gishu and Elgeyo Marakwet are yet to vote. Their opinion, though important, is now moot as the Constitution requires only a minimum of 24 county assemblies to approve such a Bill before it heads to a national referendum.

Promises and perils

From the two extremes, the BBI is full of promises and perils. But both the proponents and opponents agree that it will change the political and economic structure of the country if Kenyans approve the proposed amendments at a referendum, which many say will happen before June.

To the BBI advocates, the proposed constitutional changes will end Kenya’s cycle of electoral violence by ensuring inclusivity in decision-making and resource distribution; prop up an accountable Judiciary; ensure equitable gender representation at all public levels, including in Parliament; send more resources to the grassroots by enhancing the share of national funds to the counties; and introduce a Ward Development Fund.

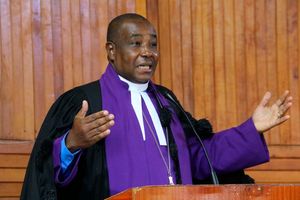

Former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga.

Rushed process

On the other hand, its opponents see a rushed process at the behest of two individuals whose political ambitions post-2022 are, at best, unclear.

“The 2010 Constitution was a revolution in itself. Now it is being torn into pieces, completely,” former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga told the Nation.

“It is going to give birth to a dictatorship, and the politics of division will come back. It will be a brutal dictatorship. That is what is going to happen. A dictatorship of the government and the Opposition. I think we are back to where we were in the 1990s, when we were fighting for the Second Liberation.

Dr Mutunga said the right procedures have not been followed in the process of nodding through the BBI proposals, and that public participation has been thrown out of the window, especially in county assemblies.

“Some people say that BBI is a coup d’état, I sympathise with that position,” he said.

“I think BBI has violated all the procedures. Even though they are going to get the result, they have not followed the constitutional procedures. People’s participation has been subverted in counties.”

The opponents have also raised issues with the cost of running an expanded Executive and Legislature, and also charge that the promised 35 per cent of equitable share to the counties is a mirage, given that the government has not been able to even attain the current requisite 15 per cent.

Prof Winnie Mitullah who argues that the extreme ends of the BBI debate are a pointer to how the post-BBI Kenya will look like.

Prof Winnie Mitullah argues that the extreme ends of the BBI debate are a pointer to how the post-BBI Kenya will look like.

“If this Bill passes, it will herald structural changes in key organs of the State and governance. But, really, it is a mixed bag. How we manage the process is going to determine if we get what we want — which is some semblance of unity,” she said.

According to Prof Mitullah, the near unanimity with which the county assemblies have approved the BBI Bill, if reflected at the referendum, would be good for the country heading into the 2022 elections.

Expanded Executive

With regard to governance, the BBI promises an expanded Executive consisting of a president, deputy president, prime minister and two deputies and Cabinet ministers.

While the President will remain the Head of State and government and Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Forces, the role of the Prime Minister will be at the behest of the President. The PM will supervise the day-to-day execution of the affairs of government, both as a member of the Cabinet and leader of government in the National Assembly.

The creation of the new Executive positions also remodels Parliament by bringing the government back into the Houses as the PM will sit in the chamber and some of the Cabinet ministers will be appointed from among the members of Parliament.

“It will change the way Kenya has been governed,” said Suna East MP Junet Mohamed, who co-chairs the National BBI Secretariat.

“Kenya has never had a broad-based governance system, except the one that was done after the 2007 post-election chaos on a ceasefire arrangement. Now we are going to have a broad-based governance system which is anchored in the Constitution.”

On that note, Mr Mohamed sees a blossoming Kenya post-BBI: “We expect that those leaders will be coming from different regions, different communities and different religions. That will create the desired inclusivity that we have been yearning for.”

Justifying the proposal for an expanded Executive, the taskforce that drafted the document hailed the new structure as more inclusive as “it will not generate the same bitterness and tension we see when the fight is for the position of the President”.

Share positions

But Deputy President William Ruto — who on Friday announced that he would not lead a ‘No’ campaign against the Bill — and his allies have often derided the proposals as a move by dynastic families to share positions among themselves instead of creating jobs.

“BBI is about how some people will share power,” the DP said on Friday in Nandi.

“But the most important issue we should be talking about is how we will be able to generate opportunities for jobs and entrepreneurship.”

There will also be notable changes to the Cabinet, with secretaries reverting to being called Cabinet ministers.

For the proponents of the BBI Bill, the biggest selling point of the proposed changes is that counties will now get 35 per cent of the equitable share of public funds, up from the current 15 per cent. In addition, it entrenches the Ward Development Fund in the Constitution, signalling more money to the grassroots. Already, the National Government Constituency Development Fund (NG-CDF), a devolved fund for which MPs are the patrons, sends billions of shillings to the regions every year. With more money going to the counties, the proponents envision creation of jobs for Kenyans.

Hollow proposal

Yet critics, like Dr Mutunga, see trouble in that proposal. Dr Mutunga says that the proposal is hollow because the national government has never been keen on meeting the bare minimum due to the devolved units under the current terms.

“If they are saying that counties are going to get 35 per cent, why are they not getting the 15 per cent now? If you talk to any of the governors they will tell you that their development budgets are not financed, and that sometimes even their salaries become a problem because the centre is not really complying with the Constitution,” said Dr Mutunga.

For Dr Mutunga and the opponents of BBI, fully implementing the 2010 Constitution would address the issues BBI is raising.

“After we got this Constitution we thought we had the victory and we did not do much to implement it. Now we have been caught with our pants down. The struggle is now going to be when people realise that this (the 2010 Constitution) was not a bad document after all,” he said.

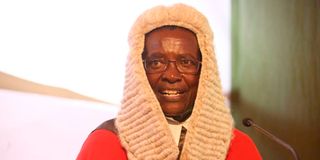

Former Chief Justice David Maraga.

Additional constituencies

In Parliament, there will be 70 additional constituencies and the re-introduction of the leader of official opposition, to be occupied by the runner-up in the presidential election. The new seats in Parliament are meant to take care of the two-thirds gender requirements, as there is an opportunity to nominate up to 180 additional male or female MPs, depending on the gender ratios, if the two-thirds requirements are not met at the ballot.

Before he retired, former Chief Justice David Maraga recommended to President Kenyatta to dissolve Parliament for failure to enact a law to entrench equitable gender representation. But the recommendation was challenged in court and the matter is yet to be decided. With the BBI, the supporters argue that such deficiencies will be dealt with and the creation of the 70 new constituencies will also bring services closer to the people.

Analysts at the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) have put the cost of the expanded Parliament at Sh3.7 billion a year, yet another potential turn-off for would-be BBI supporters. If Kenya has to nominate 180 women, the bicameral Parliament will have 640 members, up from 416, punching an extra Sh308 million hole in government coffers every month and Sh3.69 billion a year.

If the two-thirds gender requirement is met at the ballot, taxpayers will still have to pay an extra Sh726 million a year — or Sh60.5 a month — to cater for the additional MPs.

At the same time, the hierarchy in Parliament will also change. The new power structure, in order of seniority, will be the Speaker of the National Assembly, Prime Minister, followed by the Leader of Official Opposition. Currently, the order of precedence in the National Assembly is the Speaker, Leader of Majority and the Leader of Minority.

Other notable changes to the Constitution that county assemblies approved include the establishment of the Office of the Judiciary Ombudsman. This independent officer will be nominated by the President and approved by Parliament, and upon appointment will be an ex-officio member of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC).

Critics have pointed out that the proposal to create the position will interfere with the independence of the Judiciary as the holder of the office will be an appointee of the Executive who will be overseeing another independent arm of the government.

“The constitution vests in the JSC, an independent commission, the responsibility of ensuring the independence and accountability of the Judiciary. The result of the BBI proposal is a direct conflict and duplication of roles between the Ombudsman and the JSC. The risk of parallel complaints being instituted with the JSC as well as Ombudsman and the possibility of different decisions being arrived at is real and may result into a constitutional quagmire,” Mr Maraga noted before he left office.

With the country now assured of a referendum, possibly by June this year, the ongoing debate over BBI will determine the future of the country. And, by the look of things, it will be quite different from the Kenya many have grown up in.