JM Kariuki (left) and President Jomo Kenyatta.

On Sunday, March 23, 1975— a fortnight after the brutal assassination of JM Kariuki—President Kenyatta’s inner circle orchestrated a grand military spectacle through the heart of Nairobi. By displaying state power, Jomo Kenyatta was sending a signal to dissenters that the government would crush any flicker of dissent.

As the tanks growled and rolled down the avenues, the soldiers, clad in full regalia, marched with steely precision, as a reminder of the regime’s unyielding grip. The silencing of JM had ignited nationwide outrage, unleashing a wave of defiance the government had not anticipated. Public anger was reaching new heights as fear gripped the political elite.

On that day, jets from the Kenya Air Force roared over Nairobi, as Jomo Kenyatta, in military uniform, stood resolutely upon a makeshift dais, receiving the salute with an air of unassailable authority. Jomo watched as the armed forces—army, navy, and air force—marched in a calculated display of might. Flanking the President were Vice President Daniel arap Moi, Army Commander Jackson Mulinge, Kenya Air Force Commander Dedan Gichuru, Navy Commander Jimmy Kimaro, and Chief of Police Bernard Hinga. The message was unmistakable: the regime’s command over force remained absolute.

A portrait of Nyandarua MP Josiah Mwangi Kariuki, popularly known as JM Kariuki.

Kenyatta’s aim was to reassert control over the volatile political landscape. It is said that Cabinet ministers, once eager to showcase their status, now avoided flying the national flag on their vehicles, wary of drawing attention. Public rallies, once a stage for political theatrics, had been banned as well as any demonstrations.

A new Kenya was being born.

Loyalty ceremonies

Beyond the show of military might, a series of loyalty ceremonies unfolded in central Kenya and Nakuru. Delegations, handpicked and rehearsed, made the pilgrimage to Kenyatta’s Gatundu home, pledging unwavering allegiance to the aging leader. It was an orchestrated display of submission, a desperate attempt to shore up a crumbling facade of unity. Only violence and silencing of the alternative voices could rescue the state.

In Parliament, MPs hitherto subdued had found a new voice. The leader of government business, Daniel arap Moi was forced to apologise after he misled the House on JM’s whereabouts: ‘I did it in good faith. I am sorry, I am sorry.’

As Moi would later write in his autobiography, Kariuki’s murder affected the Kiambu politicos who bore the blame: “The Kiambu elite took full advantage of [Kenyatta’s] incapacity, exploiting his name and regularly forging his signature on official purchasing documents as they feathered their own nests. It was as if the murder of J. M. Kariuki signalled a free-for-all as the ruling elite scrambled for their own piece of Africa. Within a matter of months, the country teetered on the brink of economic and political anarchy. Land-grabbing became the norm, police-sponsored robbery was endemic, while ivory poaching and coffee smuggling, thanks to a worldwide boom in prices, reached epic proportions.”

The late politician Josiah Mwangi (JM) Kariuki.

As JM was buried, Mwai Kibaki was the only Cabinet minister who dared to go to Gilgil where the legislator was laid to rest. With quiet resolve, he made it clear—his presence was not political but personal, a tribute from a friend. He would later be accused by Wanyoike Thungu, during a loyalty pledge mission to Gatundu, of being disloyal. In the Kenyatta succession, Kibaki belonged to a group that rallied behind Vice President Daniel arap Moi who was disliked by the Kiambu elite, apart from Charles Njonjo, the attorney General. At the funeral, Central Provincial Commissioner, Simeon Nyachae, was heckled as he struggled to read President Kenyatta’s condolence message. The message from the people was clear— and their grief had turned into anger.

In the corridors of power, fear and calculation reigned. Kenyatta and his senior ministers retreated from public view, their absence a tacit admission that some battles were best fought from the shadows.

On 14 March, Parliament, long subdued, finally found its voice. In an unprecedented move, it appointed a Select Committee to probe Kariuki’s brutal murder. At its helm was the outspoken backbencher Elijah Mwangale from Bungoma, joined by Butere’s Martin Shikuku, the fiery Jean Marie Seroney, and a cadre of Kariuki’s closest allies. Their mandate was clear—to unearth the truth.

Kenyatta moved swiftly

Enraged by his ministers’ faltering resolve, Kenyatta moved swiftly. He convened an emergency Cabinet meeting, his fury palpable. One by one, his ministers stood before him, and one by one, they were made to pledge unwavering loyalty. There was no room for dissent – not under Jomo Kenyatta.

As reported yesterday, the Parliamentary Select Committee, undeterred by mounting obstacles by police and Kenyatta men, laid bare the grim truth—government officials stood implicated in the assassination of Nyandarua North MP.

In Parliament, the battle lines were drawn. Attorney-General Charles Njonjo, ever the government's shield, mounted a staunch defence. With calculated political precision, he urged the House to merely ‘note’ the report rather than adopt it, dismissing its conclusions as ‘biased and prejudicial.’ He hadn’t realised that the tide had turned. He also invoked the principle of collective responsibility in order to lock in government figures.

After a marathon debate, the unthinkable happened. The government suffered a rare and humiliating defeat. Backbenchers, emboldened by the moment, joined forces with rebels from within—Cabinet Minister Masinde Muliro and Assistant Ministers John Keen and Peter Kibisu defied the party whip, standing on the side of truth. When the final vote was cast, the report was accepted, 62 to 59. Asked why he voted against the government, Masinde Muliro said there was no collective responsibility in murder.

President Kenyatta poses for a group photograph with the Parliamentary Select Committee, which presented him with their report on the murder of JM. Kariuki.

Kenyatta’s wrath was swift and unrelenting. The three dissenters were unceremoniously dismissed, their defiance met with the full force of presidential authority. Loyalty was now not a matter of conscience—but an unbreakable decree.

None of those implicated in the report was asked to vacate their positions pending investigations.

Initially, the government sought to contain the fallout through orchestrated loyalty demonstrations across Central Province, Embu, Meru, and Nakuru. Led by Kikuyu MP Kihika Kimani, these rallies denied any government involvement in Kariuki’s murder, called for national unity, and attacked those spreading "rumors." Kenyatta himself, despite his declining health, delivered fiery speeches, warning of severe consequences for anyone threatening the stability of his rule. In one instance, he declared in Nakuru, "We shall have to trample the wreckers underfoot, to finish them off completely... we shall mow them down like grass." In Mombasa, he reinforced this message, ominously suggesting that "Those who speak ill of the government and propagate rumors... should realise that pangas are still in stock and could be put to use if the need arises."

At the University of Nairobi, students and intellectuals, emboldened by Kariuki’s radical populism, openly protested. A month after JM’s death, the newly-elected MP for Dagoretti Dr Johnstone Muthiora died of “blood poisoning” at a Nairobi hospital – triggering another wave of speculation. Dr Muthiora had defeated Kenyatta’s relative and physician Dr Njoroge Mungai after being backed in the race by Charles Njonjo. Again, riots hit University of Nairobi and 95 students were arrested, and the university was closed. For many years, every anniversary of Kariuki’s assassination became a recurring flashpoint for student-led demonstrations – a remainder to Kenyatta’s government that this was a pending issue.

Over the next two years, a crackdown of the media, academia and parliament started as state systematically dismantled dissenting voices. Eight prominent MPs—Jean-Marie Seroney, Martin Shikuku, Chelagat Mutai, Wasike Ndombi, Peter Kibisu, Mark Mwithaga, Koigi Wamwere and George Anyona—were either detained or jailed on politically motivated charges.

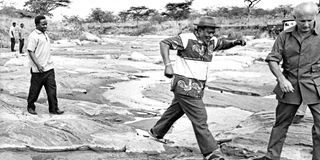

Jomo Kenyatta (centre) during a visit to Lake Bogoria. Behind him is his then secretary, JM Kariuki.

Wamwere was detained in August 1975 for demanding accountability on the land-buying schemes in his Nakuru North constituency. The same month, Mark Mwithaga, vice-chair of the Kariuki Select Committee, was jailed for a “domestic assault” case that had taken place two years. Kibisu, who had voted against the government on the Kariuki report, was jailed for assault in October, 1975.

He was charged on the same day he was sacked and subsequently lost his seat. Seroney and Shikuku found themselves detained without trial over remarks made within the House—once considered a bastion of free speech. On the evening of 9 October 1975, Seroney, serving as Deputy Speaker, refused to compel Shikuku to substantiate his provocative assertion that "Kanu was dead."

When Kihika Kimani demanded clarification, Seroney, with his characteristic audacity, delivered the now-infamous retort: "We don’t substantiate the obvious." This boldness disturbed the establishment, culminating in their arrest and detention on 15 October 1975, right within the halls of Parliament. In the aftermath of JM Kariuki’s assassination, the post-JM Parliament had become a perilous ground where free speech was no longer sacrosanct.

At the University of Nairobi, lecturer Ngugi wa Thiong’o was detained for staging the Kikuyu play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I will Marry when I want) which was critical of elite capture of the state. This was a lesson to the radicals within the academia that creative writing could also be criminalised.

Kariuki’s assassination thus marked the definitive transition of the Kenyatta state into an era of intensified repression. What had once been a loosely managed system of patronage, allowing limited space for dissent, became an outright authoritarian regime. Fear replaced debate, and targeted purges silenced even the most resilient critics. While the state emerged victorious in crushing opposition, Kariuki’s death radicalised a generation, setting the stage for the political turbulence that would follow Kenyatta’s eventual demise in 1978.

Kariuki’s death was more than just the silencing of a political firebrand. His death reworked the Kenyatta succession as a formidable challenger had been eliminated from the race. Interestingly, the assassination had shattered the credibility of Moi’s Kiambu adversaries, who found themselves implicated, directly or indirectly, in the orchestration of his demise. The political landscape shifted as the anti-Moi group tried other means to get rid of him.

The 1976 Change-the-Constitution move was a brazen attempt by the Kiambu mafia to eliminate Moi as a contender. This was silenced by Njonjo—though other plots, including the setting up of an elite Anti-Stock Theft Unit as a political machine was one of the post-JM plans to manage the Kenyatta succession.

By setting up the unit in Nakuru, where Kiambu power-brokers held sway, it was thought that if Kenyatta died in Nakuru they would control the transition. Luckily, Kenyatta died in Mombasa as Eliud Mahihu, the Coast Provincial Commissioner and JM’s friend watched. Geography, timing, and political miscalculations sealed the fate of those who had sought to sideline Moi.

In Central Kenya, Kariuki’s assassination became the lens through which the Kikuyu analysed the Kenyatta regime—a betrayal so profound that they never forgave him and the Kiambu mafia.

Tomorrow: The lasting legacy of JM

@johnkamau1 email: [email protected]

Also read:

PART I: The day JM Kariuki vanished