President Uhuru Kenyatta (centre), Deputy President William Ruto (left) and opposition leader and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga during the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) report launch in Nairobi.

| File | Nation Media GroupPolitics

Premium

The making and breaking of political alliances

What you need to know:

- Political elites in Kenya belong to the same WhatsApp group.

- The only difference is that a few of them are administrators inviting others to join.

Many people from outside Kenya find political developments in the country confusing and difficult to understand. A common view is that Kenya is always restless and shaky. They have the image of a country tottering and tending to collapse. But there are still others who view Kenya as incredibly resilient.

At one time the country appears shaky and unstable. But within a short period of time, the country regains momentum and moves on. And as it moves on, politicians are at war with one another again. Those who were friends suddenly become hostile to one another. They become opponents and bitter foes.

The present political situation shows this incredible state of development. In the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections, President Uhuru Kenyatta and his Deputy, William Ruto, were together running on the same party ticket. They mobilised support from their respective ethnic groups and won the election. On the opposite side was ODM leader Raila Odinga.

In 2013, Mr Odinga formed an alliance with ethnic elites from other regions. He had Mr Kalonzo Musyoka from Ukambani; and Mr Moses Wetang’ula in Western Kenya. In 2017, Mr Musalia Mudavadi joined them to form the National Super Alliance (Nasa).

Today, these alliances have literally broken up. They have broken up after President Kenyatta and Mr Odinga ended their hostility. In March 2018, they agreed to work together, “shook hands”, and established the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), in which there have been proposals to amend the constitution to create conditions for inclusive politics. The BBI has literally killed the existing alliances. It is gradually shaping up new ones.

This picture of changing alliances; falling out; and teaming up again and leaving the country somehow on the move confuses outsiders. Other countries in the region lack this resiliency. They are held together by the ‘Big Man’ who provides direction on everything.

This is not so in Kenya, at least since the exit of President Daniel arap Moi in 2003. There is no ‘Big Man’ but several ‘Big Men’ always in competition at the national level. This form of competition is repeated all the way to the grassroots.

Who shapes politics and violence in Kenya?

If Kenya does not have one Big Man to drive major political events, what then makes it easy for the several Big Men to drive political developments and to compete without collapsing the country? Why can’t any of these Big Men dominate others?

The Big Men of Kenya’s politics are leaders of only the large ethnic groups. They get to leadership by mobilising their large communities to compete. This is made possible by several things. One, Kenya practises a ‘winner-takes-all’ politics. At election, those who win control political power and begin by excluding those who lose. Those who lose also begin immediately to craft new alliances or challenge the existing one.

Two, Kenya uses an election system in which numbers determine everything. And it is not the population figures that matter. The number of registered voters matters. This is because to win a presidential election, the constitution now requires a winning candidate to have 50 per cent plus one vote.

There is also the requirement that one must have visible support in at least half of the 47 counties by acquiring not less than 25 per cent of the votes in at least half of these counties. This is an incentive to form alliances to compete at election time. To get the numbers, elites turn for support even from rival politicians. One must seek support from even the rivals because they have informal power and control over their groups. This makes the alliances to be rarely stable.

Political stability or political violence around election and after results from how the alliances and political deals are made, maintained, and managed. Broad based alliances comprising many ethnic politicians lead to stability. This happens because it helps the leading politicians to secure their political and economic interests.

This in turn gives hope to their communities, which are made to believe that their future is tied to the future of these politicians. And since the government and the presidency are a dominant feature in power arrangements, communities keep on waiting for the turn for their elites to be in power to benefit.

The organising question for election

But making of alliances and fragmenting them is not the main factor that leads to instability and violence. The questions the alliances crafted for mobilising political support is central in determining whether the election is going to be peaceful or violent.

In 2007, for instance, there were two competing questions presented by the two main alliances at the time. President Mwai Kibaki’s Party of National Unity (PNU) campaigned on a platform of economic growth and recovery.

Newly elected President Mwai Kibaki (centre) at Uhuru Park, Nairobi, makes a speech after his predecessor Daniel arap Moi (left) handed power to him following the 2002 elections.

The opponent, Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) of Mr Raila Odinga, presented a rival question focusing on political inclusion. They argued that benefits of recovery and growth were concentrated in the hand of Mr Kibaki’s Kikuyu and related elites and their communities because the government was not inclusive.

The 2007 campaigns and the subsequently disputed elections led to unprecedented political violence and the formation of a “truce” Grand Coalition Government between President Kibaki and Prime Minister Odinga.

The 2013 and 2017 election organising questions

There was a consensus among the parties that making the 2010 constitution work was important. This led to a narrative of peace as the main issue of organising the election. There was no strong opposition to the peace narrative. In addition, the International Criminal Court cases facing Jubilee’s Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto —who eventually won the elections— loomed large. The two, as President and Deputy President respectively, were left off the hook by The Hague-based court years later.

The 2017 election had several questions competing for attention. President Kenya and his deputy campaigned on a platform of development of infrastructure such as roads and the Standard Gauge Railway. But Mr Odinga and his Nasa coalition—including running-mate Mr Kalonzo, Mr Mudavadi and Mr Wetang’ula —upended this question.

A National Super Alliance (Nasa) supporter in Kisumu faces police officers on October 27, 2017, during a protest against the second presidential poll.

They argued that public debts arising from borrowing to support the infrastructure would collapse the economy at some point. They presented a different organising question with a focus on strong governance and specifically electoral justice, and working of institutions.

These two separate questions, development vs electoral justice, laid a foundation for tensions throughout the electoral process. Lack of a common question resulted in the post-2017 election which was resolved, again, by revisiting the governance/electoral justice question through the BBI thinking.

The organising question for 2022 elections

The organising questions for the 2002 election are very much in place. And the questions are in conflict. On the one hand, Deputy President Ruto is presenting what he calls the Hustler vs Dynasty narrative – or working way up to power from humble background.

The “Hustler Nation” narrative pushed by Mr Ruto’s camp also focuses on unemployment and building local economies to improve people’s wellbeing. This narrative resonates with ordinary people, the unemployed, the poor and those who feel the leaders have let down the poor. On the other hand, this narrative points at the dynasty as privileged few. These are those leaders who have risen to power on account of family influence and privileges.

The hustler narrative as an organising question is unique because it aims at mobilising along class and income lines. It is about the rich and the poor. The only time that this happened was around 1974 and 1975 period when Mr Josiah Mwangi Kariuki (popularly referred to as JM Kariuki) wanted to mobilise the peasants against the new political elites. JM was popular with peasants for fighting for land redistribution. He argued that Kenya had become a country of ‘10 millionaires and 10 million beggars’. He continued with his criticism of the government until he was assassinated in March 1975.

Mr Ruto is not JM Kariuki. He cannot be. But he has picked divisions between ‘the rich and the poor’ or inequalities to shape a new type of organising question in Kenya today. His hustler narrative gives him one simple advantage which other politicians do not have. He has used the hustler narrative to endear himself with the army of unemployed youth, the ordinary voters, and the poor. He has presented himself as a son of a poor peasant but has risen to power through hard work. He is able to reach any community without senior ethnic leaders from the community.

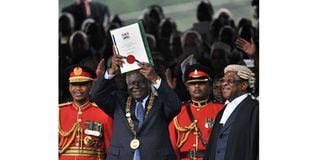

President Mwai Kibaki lifts up the new Constitution soon after its promulgation at the Uhuru Park grounds in Nairobi on August 27, 2010.

To repeat, Mr Ruto is not JM Kariuki. He does not talk about fighting corruption. Nor does he criticise any government policy. He has been part of these policies. He does not talk about millions of beggars or presented himself as the fighter of the rights of the poor people.

Whether the hustler narrative will translate into votes is a matter of debate. What is certain is that it is becoming a new way of organising politics. Ethnic leaders are generally feeling uncomfortable because some of them are painted as a ‘dynasty’. They have grown up in a life of privilege.

Critics calls for caution in what they see as mobilising the poor against the rich. Organising politics on basis of the rich and the poor will bring about class conflict. It will result in divisions and violence that no one will have control of. They have chosen to fight off the hustler narrative by threatening anyone mobilising the poor against the rich. They have chosen to be inclusive politics and distribution of political power as an answer to problem.

The dynasty narrative does not explain how to address unemployment and challenges facing the poor. The dynasty does not address the issue of huge loans borrowed to support infrastructure. They do not pretend that they will not borrow loans to do development. How this will translate to votes is also a matter of wait and see.

Politicians belong to the same WhatsApp group

These dynamics show that political elites in Kenya belong to the same WhatsApp group. The only difference is that a few of them are administrators inviting others to join. At present it appears as if Mr Ruto, Mr Odinga, and President Kenyatta are the main administrators in the WhatsApp group. But it is a matter of time before we see ‘lefting’ and more invitations to join the alliances.

The 2022 elections will not be an easy political event. Already the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) process, a result of the March 2018 handshake, has suspended the plans that politicians were going to use to develop new alliances to create political inclusion.

Those opposed to BBI and particularly those in Mr Ruto’s hustler side, argue that the BBI was going to be a tent for distributing patronage. If it does not work then the better for them. The collapse of BBI would mean that all politicians go back to the drawing board to develop new alliances. It will have profound impact on the making of alliances and may alter the questions around which to organise the 2022 election.

Whichever way the BBI goes — and an appeal is pending at the Court of Appeal with a decision expected in July — the competition will be between the hustler narrative and whatever comes up after the BBI matter is settled.

Prof. Karuti Kanyinga is based at the Institute for Development Studies (IDS), University of Nairobi; @karutikk; [email protected]