What Ruto and Raila have to consider in picking deputy

As Deputy President William Ruto and Former Prime Minister Raila Odinga conclude their search for running mates in their respective presidential bids, both will be taking a keen look at the present Kenyan situation.

They will also both be taking a long look at the history of the dynamic and power relations both in Kenya and comparative jurisdictions.

They might refer back to James Garner, the US Vice President between 1933 and 1941, who famously described the office as being “not worth a bucket of warm spit” (sometimes reported as “warm piss”). Derision for the vice presidency has since continued as a constant feature of American politics, yet, ironically, it remains one of the most sought-after offices in the land.

Kenya is no exception as the office of Deputy Presidency comes with no specific job description. The fractured relationship between President Uhuru Kenyatta and DP Ruto is just a more extreme form of previous spats within the institution we now call the presidency.

Examples abound. After independence, there was the split between President Jomo Kenyatta and Vice President Oginga Odinga. Then there was long-serving and long-suffering Vice President Daniel arap Moi and his travails under the Kenyatta administration. Then there’s the humiliation President Moi subjected a succession of his deputies starting with Mwai Kibaki.

Why then such allure for the office? Simply because the vice president is first in the line of succession.

The idiom “a heartbeat away from the presidency” describes accurately the only clear role of the Deputy President, which is to sit idle until the day he or she may be called in to fill the gap in the event the President dies in office, resigns or is impeached.

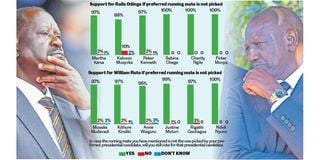

The public tussling being witnessed within the Azimio la Umoja One Kenya Coalition as Wiper Party leader Kalonzo Musyoka loudly demands the right to deputise Mr Odinga indicates a movement heading towards implosion. The rival Kenya Kwanza alliance of Dr Ruto has also had its fair share of jockeying for the position, but has managed to paper over the cracks and limit any discussions to the inner sanctums.

The noise in Azimio played out in public raises questions on whether Mr Odinga and Mr Musyoka can ever work together again work.

Mr Musyoka was Mr Odinga’s running-mate in two unsuccessful presidential bids, 2013 and 2017, and feels he has earned the right to have another go. The problem is that the increasingly shrill demands and threats have taken on the characteristics of blackmail. That, of course, militates against everything that informs a successful pairing.

Chemistry and trust remain vital components in all the permutations that inform the selection of Deputy President. There will of course be many other considerations, including a balancing of the ticket and ability to bring in substantial votes.

An interesting element of the ongoing drama was the recent “leakage” of purported gradings of running mate aspirants from both Azimio and Kenya Kwanza. Both lists were patently fake, but remain of interest because it is likely they were released by groupings within the respective parties as trial balloons or as attempts to influence the process.

The purported Azimio list, for instance, placed Mr Kalonzo near the bottom of the pile. He was ranked highest on regional factor, which recognises the Lower Eastern votes he could bring to the ticket, but fared most poorly on “compatibility with the candidate”.

The rankings supposed to have come from Kenya Kwanza were also quite interesting. It placed Tharaka-Nithi Senator at the top of the list. It was telling that whereas Dr Ruto’s campaign is normally quick with furious denunciations of false or misleading media reports, it this time remained notably mute on the Kindiki headline in one national newspaper.

Even if both lists were fake, they captured accurately the almost universal criteria for choice of a running mate – trust, loyalty and compatibility.

If the Kenyan presidency is partly adopted from the American system, experiences from across the Atlantic can provide useful lessons on the running-mate conundrum. In her July 2020 book Picking the Vice President, Elaine Kamarck wrote that in the past, a running mate was essentially selected to “balance” the ticket in terms of regional, ideological and even demographic considerations. That is why a young northern liberal like John Kennedy picked an older running mate from the conservative southern heartland, Lyndon B Johnson. Those, she argued, were marriages of convenience that often did not work if the pair did not click.

Bill Clinton bucked the trend by selecting “lookalike” Senator Al Gore, changing the model from “balance” to “partnership”. That had the effect of giving more meaning to the office as the pair were on the same wavelength on most issues and the VP played a critical role in driving the president’s agenda. A similar dynamic was seen with George Bush and Dick Cheney, and Barack Obama and Joe Biden.

What changed was the presidential nominee having a freer hand to select a running mate of his preference, instead of being forced to pick rivals brandishing their numbers. The dynamic between President Kenyatta and DP Ruto provides a classic example of what can go wrong when the ticket is not in sync.

On the surface, UhuRuto seemed like a match made in heaven. It exhibited youthful vigour and captured the imagination with the harmony displayed on stage – matching outfits, camaraderie, addressing audiences in tandem, and all. The reality, however, is that the two had nothing in common other than the twist of fate that brought them together in joint pursuit of power.

The two first came together in 2002 when outgoing President Daniel Moi handpicked Mr Kenyatta as his preferred successor, with Ruto a key player in the effort. After losing the 2002 elections to President Kibaki, it did not take long for Uhuru and Ruto to go their separate ways.

As the Narc coalition that had propelled Kibaki to power disintegrated midway through the first term, Uhuru—who headed the official opposition as leader of Kanu—cast his lot with the president with an eye on inheriting the Mt Kenya voting bloc. Ruto went to join the nascent opposition coalescing around Raila in the new Orange Democratic Movement.

Come the aftermath of the disputed 2007 elections, President Kenyatta and DP Ruto found themselves at the International Criminal Court accused of being key drivers of the post-election violence, but on opposite sides.

The cases collapsed, but both adroitly exploited the situation to galvanise political support within their respective ethnic formations where they were seen as heroes. In time they came to reunite not as presumed leaders of rival combatants, but as joint victims of the ICC and the local political groupings that had pushed for prosecution.

Midway through their first term, however, it started becoming apparent that UhuRuto bromance was fading. When President Kenyatta launched his much-hyped war on corruption in 2015 by dropping a number of Cabinet ministers, DP Ruto’s allies loudly complained that their side was being targeted.

The chemistry was no longer there, but the two remained tied at the hip for the sole purpose of seeking re-election in 2017. Soon after that was accomplished, it was not long before the first public signs of impending breakup were seen early in 2018 when the President sought a new ally in opposition leader Odinga. After that it was all downhill, with a forced amity degenerating into open hostility.

Even before the Jubilee break-up, Dr Ruto had started selling the “Hustler versus Dynasty” narrative, making it clear that he placed both President Kenyatta and Mr Odinga in what he considered pampered scion of Kenyan political royalty, alongside their colleague Gideon Moi.

The differences between the President and his deputy are not grounded in ideology or policy differences, but the simple fact that the two were not compatible in the first place. Theirs was a marriage of convenience rather than a coming together of like minds.

Behind the façade of a friendly partnership, there was mistrust and mutual contempt. In unguarded moments, President Kenyatta would disclose that he considered his deputy a bit too uppity and ambitious. And it is no secret that Dr Ruto considered the President lazy and unfocussed, and too often distracted by love for drink.

Dr Ruto has often said that he learnt from President Moi the virtues of loyalty and patience that make for a successful Vice President. However, Moi, as Vice President, never started campaigning while his boss was still in office, nor assemble a cast of characters to insult him in public.

If Dr Ruto was indeed contemptuous of President Kenyatta and impatient to succeed him, then it follows that he is already familiar with the traits that he will not want in a deputy. He will want one who will be loyal and dependable, in addition to the obvious need to balance the ticket in terms of region and able to bring in substantial votes.

He will not want a DP who will challenge his authority or easily establish an independent power base to ease his own push for power. Mr Odinga, from the other side, will be looking at roughly similar considerations.