Premium

Rogue Kenyatta bodyguard who was symbol of impunity

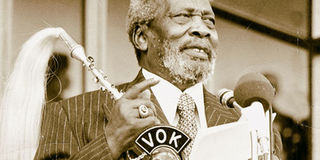

Kenya's first President Jomo Kenyatta. Wanyoike Thungu and the President first met when Kenyatta returned from his long stay abroad to join the freedom movement in the mid 1940s. PHOTO | FILE | NATION MEDIA GROUP

What you need to know:

- Thungu and his types were such a menace because they did not have the discipline of trained police officers.

- Thungu provoked a series of events that preceded JM’s murder minutes before the politician’s body was discovered in Ngong Forest.

- His name had featured in ethnic killings and illegal oaths in the aftermath of assassination of cabinet minister Tom Mboya in 1969.

Many in my generation who were young journalists in the early 1990s had the courage of a brass monkey.

We yearned to tell the untold story, and to venture where the eagles dared.

Without commitments that come with age, we felt there was nothing else to lose except the story itself.

It is in that spirit that one morning I suggested to my boss, Kenya Times Features Editor Gray Phombeah, an interview with Wanyoike Thungu, the much feared former bodyguard of President Jomo Kenyatta.

At the time, the retired bodyguard, who has since passed away, was still hale and hearty — and perhaps as deadly.

“Are you sure you want to talk to that man?” my boss asked.

“The man was a live wire in his time and most likely he wouldn’t take kindly to anybody keen on opening his can of worms.”

Not to give up, I told my boss that the former bodyguard hailed from the same place as my maternal family — Gatundu in Kiambu County — and that I had overheard my uncles say he and my grandfather were acquaintances from their days in the struggle for Kenya’s independence.

“All right, then you can give it a try,” my boss said, “Invoke the name of your grandfather and see whether that can make him talk. Even giving you audience alone can be a story since he has never talked to the media.”

***

I had gathered the retired bodyguard was likely to be found at his business premises in Gatundu town where he whiled away the day with other pensioners reminiscing about the good times gone by.

Sure enough, we found him there chatting with friends inside his pub.

The photographer, the driver, and I settled at a table in the far corner from where we requested the old man be told we were his visitors.

He returned a message that we should write our names on a piece of paper: where we came from and why we wanted to see him.

On looking at our names, the old man ordered that I alone be taken where he was seated. I guess my name “betrayed” that I’d roots in the locality.

For a journalist, the first few seconds are very crucial in striking rapport with a possible hostile news source.

HOSTILE MEDIA

So, I was fast in mentioning my family connections which made the old man relax and gradually warm up to me.

He asked that I sit next to him and ordered refreshments for us, but said my colleagues remain where they were.

Minutes later he pulled me aside to ask what it was we wanted to hear from him. “The story of your life,” I told him.

“Your days in the Mau Mau, your life with mzee Jomo Kenyatta, just that.”

After some pause he said: “Well, I never talk to the press. They’re terrible people, and I don’t like them near me. But I will give my story to you because I knew your grandfather and now you’re my friend. However, that will not be today. You will have to come back here when you’re alone.”

“That’s fine with me,” I told him. “Just give me a day when I should come back. I can do so even tomorrow if that is fine with you.”

“Come on Saturday morning; I will be here waiting for you,” he promised.

GOOSE CHASE

To cut the long story short, I was there first thing on the appointed day, and on two other separate days.

But each time we met, the old man found an excuse to postpone the interview to yet another day that never came.

In the three appointments I had with him, I gleaned the old man just wanted me to have as much nyama choma and booze as I waited on his account, but he had no intention of giving any interview.

“He has set me on a wild goose chase,” I finally reported back to my boss. “I suspected something like that would happen,” replied my boss and joked.

“But at least you had a reunion with your ancestors as you shared nyama choma and poured libations!”

Though unable to get the former bodyguard’s story from the horse’s mouth, in the fullness of time I’d gather so much about him from people who, for one reason or the other, knew him well.

The first to give me a glimpse of the life and horrors of the dreaded bodyguard was the first African post-independence Police Commissioner Bernard Hinga.

COMMANDANT

He clarified to me that though the media kept referring to Thungu as the head of the presidential security, there never was such a title in the official security hierarchy.

He told me that then, and even now, the official title of the person heading the presidential security is Commandant, Presidential Escort, which Thungu never was.

The holder of the position at independence was one Alex Pearson, inherited from colonial police, and later Bernard Njinu, who remained in the position until Mzee Kenyatta died.

The former police commissioner also told me never in his life was Thungu a police officer, though at various times he held titles like “Inspector of Police” and “Senior Superintendent of Police”.

How did that come about? The former police commissioner told me it all had to do with the long history Thungu had with Mzee Kenyatta.

They first met when Kenyatta returned from his long stay abroad to join the freedom movement in the mid 1940s.

At the time, Thungu was a youth-winger in the pre-independence KAU party and charged with providing escort and security to leads.

Mzee Kenyatta instantly liked him because he was as tough as they come — ready to die or kill for the boss — and also because he could be trusted as a “boy” from home.

TRAINING

Come independence, President Kenyatta insisted that Thungu and a few others be incorporated in the newly formed elite presidential guard, despite their lack of formal police training.

Since age and education couldn’t qualify them for elite training in VIP protection in Britain and Israel where the presidential guard went, Thungu and his types were sneaked to Czechoslovakia for a short basic course in gun handling.

The former police commissioner told me Thungu and his types were such a menace because they did not have the discipline of trained police officers.

They were bulls in a China shop, quick on the brawn and even faster on the trigger.

The former police commissioner told me that at one time, one of them shot dead a patron at a bar in Gatundu after a quarrel over a twilight girl.

Another one shot dead a relative of a worker at one of the President’s farms on the excuse he’d never seen such a face before!

PROMOTION

Yet another one killed instead of restraining — which is what elite VIP guards are taught to do — a mad man who had rushed forward in the direction of the President at a function in Nakuru.

Eventually, President Kenyatta was prevailed upon to let go the “squad”.

However, because of sentimental attachment, he demanded that Thungu not only remain behind, but be the “head bodyguard” to be riding in the presidential limousine.

He further decreed that he be ranked as official police starting with title “inspector of police”.

Such was the soft spot Mzee Kenyatta had for his “bush” bodyguard that he ordered his name and that of then-minister of State in the President’s office Mbiyu Koinange be deleted from the report of the parliament probe committee that implicated them in the assassination of the fiery MP JM Kariuki whose body was found dumped in Ngong Forest.

JM MURDER

In an investigative series I published in the Daily Nation in March 2000, I established that Thungu provoked a series of events that preceded JM’s murder minutes before the politician’s body was discovered in Ngong Forest.

Sitting in the panel that interrogated the MP minutes after his abduction from the Hilton Hotel, Mzee Kenyatta’s bodyguard had angrily demanded to know why JM would “so much disrespect the President as to go around the country insulting the head of state as if they were age-mates!”

When JM denied the charge and began explaining, the President’s bodyguard handed him such a heavy blow to the face, knocking off all his front teeth.

In anger, JM made to reach for a pistol concealed in his jacket, but GSU commandant Ben Gethi, the only person in the room who knew JM was armed, was quick on the trigger and shot him in the shoulder to disarm him.

Knowing that at the point JM couldn’t be taken to any hospital without news of the high drama leaking, a decision was made that he be “finished” at Ngong Forest and his body given to hyenas to feast on.

Fortunately, the wild animals refused to be enjoined in the crime.

PRESIDENCY

Earlier, the name of the self-styled bodyguard had featured in ethnic killings and illegal oaths in the aftermath of assassination of Cabinet minister Tom Mboya in 1969.

The ethnic killings were targeted at communities the bodyguard and his ilk considered a threat to continued grip on state power by what they called the “House of Mumbi”.

The killings were followed by illegal oaths in parts of Central Kenya, where victims were forced to swear they shall never allow the “presidential motorcade to cross River Chania” — meaning the president of Kenya must forever come from Kiambu County.

A former head of civil service Geoffrey Kareithi told me that the ethnic “cleansing” and illegal oaths by the criminal gangs using the name of the President were such a threat to national stability that he told the head of state they must be stopped. The President agreed.

***

Names of the Kenyatta bodyguard and that of a rogue Kiambu “businessman” Kiarie wa Njoki would also prominently feature in a racket where individual property would be seized in the name of the President, especially in last days of Mzee Kenyatta’s reign when he was hardly in control.

Postscript

Coming from a social function in Gatundu not a long time ago, I gave a lift to an old man who asked to be dropped somewhere on Thika Superhighway.

Past the Kenyattas family home at Ichaweri village on Kenyatta Road, the old man pointed to me the rugged boundary of the land estimated at 40 acres on which the ancestral home is built (they own thousands of acres not far down the road).

He asked me whether I knew why it was like that, which I didn’t.

He told me it is because the Kenyattas who originally came from Maasai land only had a small portion of land — about five acres — at Ichaweri, but acquired the rest of the land through buyouts handled by Thungu when Mzee Kenyatta became president.

BOUNDARY

However, some age-mates of Mzee Kenyatta refused to be bought out despite threats from Thungu.

Instead, they requested for a meeting with the President and asked him why he was sending them a “small boy” (Thungu) to harass them when they had grown up and lived together as age-mates.

Mzee reportedly reprimanded his bodyguard and told him his age-mates must forever remain his neighbours, hence the skewed boundaries to Kenyatta’s family land at Ichaweri.

I had no way of verifying the juicy story.